The entire purpose of China’s presumed rebalancing act is supposedly that the country’s economy will no longer be strongly linked to industry. Manufacturing, for export in particular, is what made modern China into an economic powerhouse, transforming a once agrarian subsistence society (thanks to socialism). One need only look at overhead or satellite images of those cities chosen as special economic zones (thanks to a limited embrace of markets) to see these revolutionary effects.

But manufacturing in the 2010’s is out of fashion. For some reason this is a question, though the answer is as obvious as it is uncomfortable; the latter explaining why the query is never satisfactorily replied.

Without a global economic rebound to create new demand for what China might produce, what are they left to do? We know the answer here in scattered decimation throughout our own country, America. Such one-trick towns used to be booming, too, but now they are collectively known as the Rust Belt.

Not so, says Western Economists. The Chinese are brilliant, a level of envy that is both a part self-loathing as well as jealousy. Economists fancy themselves as the engineers in Plato’s Republic, the enlightened geniuses who could properly order society (they actually call them “optimal” outcomes) if given the power and authority.

In China, they have the power and authority; therefore, their schemes will work where ours certainly can’t.

Rebalancing was invented so as to keep alive this fantasy. The Chinese economy isn’t failing, they say, it’s merely being transformed into Kallipolis by proper but rational, progressive authoritarians who know what’s best and better how to achieve it – because they all studied at the same Ivy League Economics schools.

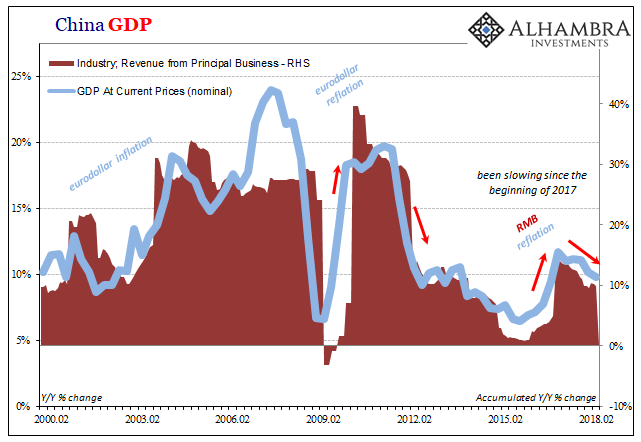

China’s actual economy, however, looks less rebalanced today than when the idea was first floated. Starting with this quandary:

There is more than a passing relationship between nominal GDP in China and the reported aggregate revenues of industry. They are, quite clearly, still linked. Which is cause, and which effect? Does it even matter?

In other words, do the fortunes of Chinese industry continue to command China’s whole economy, in which case rebalancing can be nothing more than a fiction? Or, is China’s industrial condition merely a very good reflection of China’s entire economic circumstance? Even if it’s the latter, rebalancing, still, has been merely a fiction.

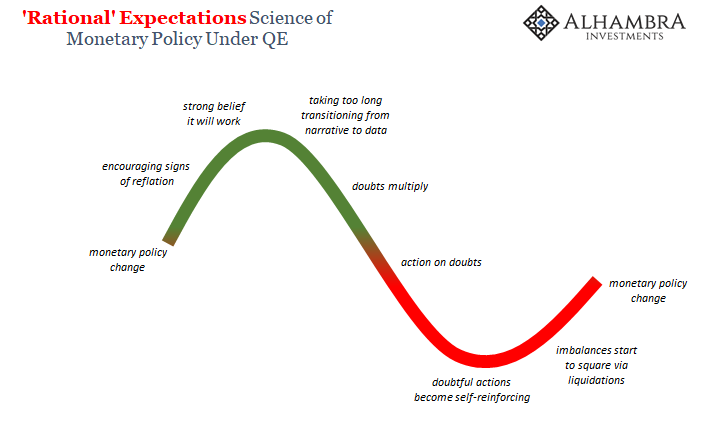

It doesn’t really matter which is which at this point, and that includes the very good possibility that both are merely captured by price reflation/deflation, meaning, as always, eurodollar.

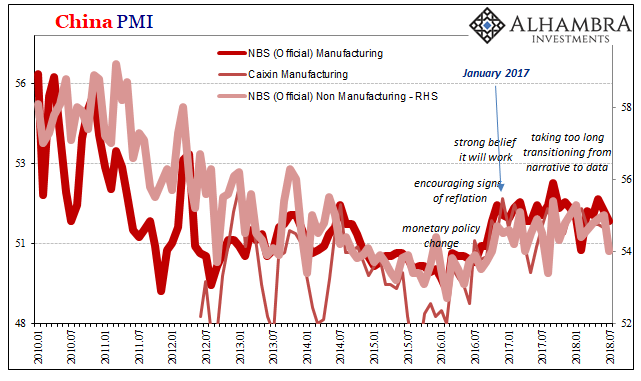

According to these crucial views, China’s part of Reflation #3 peaked a year and a half ago. That the economy there has been at best treading water for all this time, and more realistically on a 2013-style slow burn downtrend, explains a great deal about 2018 to this point. Not even the most outspoken cheerleader for this Western Economics technocracy would have made the promise of globally synchronized growth in early 2017 if they knew it was being made without including the Chinese.

China’s official PMI’s were all down in July, starting off Q3 2018 on the wrong foot. The manufacturing PMI declined to 51.2, the lowest since February. New export orders were below 50 for the second straight month, making four out of the last seven. The non-manufacturing PMI declined to 54 from 55 in June, the lowest since last August.

This would be, however, more consistent with actual underlying conditions, but wrong nonetheless in how the world is supposedly booming or just about to be. The US economy in particular has been singled out (for decoupling), but as in 2014 the Chinese beg to differ.

We’ve been here before, just four years in fact. I wrote three years and eleven months ago about China’s industry and PMI’s for that particular August and how they all profoundly disagreed with the then-FOMC’s highly optimistic assessments. It sounds today almost as if it just rolled off my keyboard:

With Brazil in recession and much of the “resource” part of the supply chain nearing that or worrying about it, you can surely bet that there are “unexpected” problems in the Chinese economy. As much as the word “decoupling” is being used once again (though in 2008 it was reversed, with the world supposedly able to decouple from US weakness) the global supply chain is acting quite consistently. That observation assumes, however, that the view of the US economy is one of deficiency and not that which floats the FOMC’s rational expectations component.

Yep, the US was booming then, too, only it wasn’t outside of official forecasts. If China’s industrial base is moving the wrong way, then you can bet there is no boom anywhere around the planet. Many markets are betting. This is what the flat yield curve is observing, still another in a very long line of FOMC forecast errors.

The world economy has been slowing almost since Reflation #3 began. Real technocrats might have noticed. But this is all pure politics, not enlightened economics (small “e”).

Stay In Touch