June was a good month for Japanese workers. Real wages rose at the fastest pace in eight years, jumping nearly 3% for the first time since 2010. The data, reported by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, was the first piece of positive economic news in some time. As you might expect, the wage figures are being taken as definitive signs the Japanese economy has finally turned the corner.

I’ve lost track of how many corners Japan has never turned. That’s actually the cruel irony of Japanification. Its lost decade, now three, was never about banks. For a good while in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, there was intense effort to clean up Japan’s zombie banking system because they were all so sure that was what was holding everything back.

The real problem wasn’t bankers, however, it was central bankers. These are the men who time after time (after time) take any small bit of positive news and turn it into the greatest thing ever that cannot possibly mean anything other than full recovery…only to forget about the thing in very short order once it inevitably leads to the same old nowhere.

This is nothing other than corruption. It’s not the what most people think when confronted with the charge, meaning that these aren’t thieves pilfering Japan’s Treasury. They are worse, in that they have plundered Japan’s economy by never giving in and admitting they have no idea what they are doing.

Japanification is therefore nothing more than the repeat of the false dawn, the hell of Bill Murray’s Groundhog Day, only capturing an entire nation (or global economy) rather than a single smug idiot from Pittsburgh.

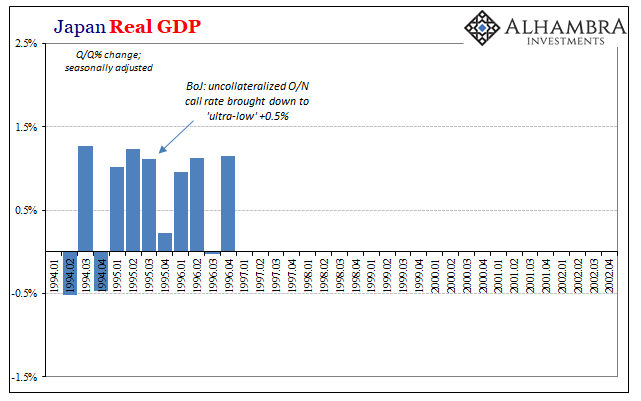

In the middle 1990’s (above), in the initial years after the bubble collapse, the Bank of Japan congratulated itself along with its government sponsors (BoJ was not “independent” in the same way Western-style central bankers were and are until 1998) for successful “stimulus.” GDP growth had resumed, and though at a lower level it was at least somewhat stable.

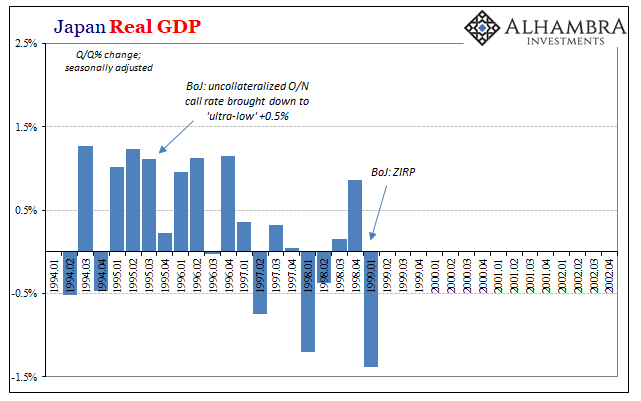

Declaring success in 1996 was premature. Japan’s economy was not stable and by 1999 it had fallen back into the worst state since 1990-91.

Undeterred, BoJ went further; cleaning up zombie banks and then “fortifying” them with the world’s first ZIRP.

By early 2000, it appeared to have worked if only based on very preliminary indications – meaning just one quarter of GDP growth. Because it stood out when compared the prior decade, there was no way, for Japan’s central bankers, it could mean anything other than successful monetary policy.

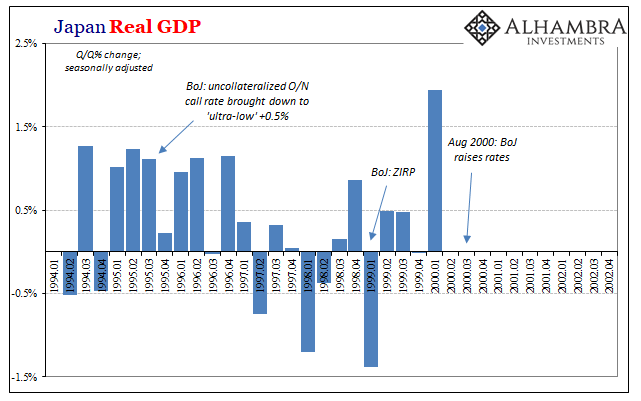

BoJ was so confident that in August 2000 they ended ZIRP and raised their benchmark money rates. You know what happened next.

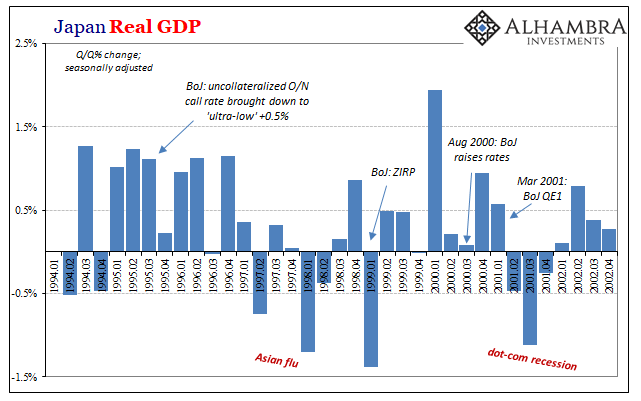

Embarrassingly, just seven months after declaring an end to one lost decade Japan’s central bank instead began a second by completely reversing itself, ditching the rate hike(s), getting back to ZIRP quickly, and adding the world’s first QE on top of it. False dawn, false dawn, false dawn.

The gyrations in Japan’s economy captured by whichever specific variable aren’t consistent with the Bank of Japan or any of its policies. Just on the charts shown above you will notice that the ups and downs follow instead overseas, or offshore, economic and monetary events; as if BoJ’s economic inputs are tiny in comparison to “something” else.

In more recent times, they’ve played the same game. Officials and Economists (same thing) appear incapable of learning. One of the chief components of any true scientific endeavor is falsification. If observation declares your theory invalid, you are supposed to move on to the next one. It’s how we all learn as humans, trial and error.

In Economics, however, but most especially the version practiced in Japan, false dawns aren’t falsifying they are treated instead as proof that the next time Economists will be right. If it didn’t work today, then there is an absolute now way it will fail tomorrow. The more failures they rack up, the bigger the guarantee. Time isn’t a factor.

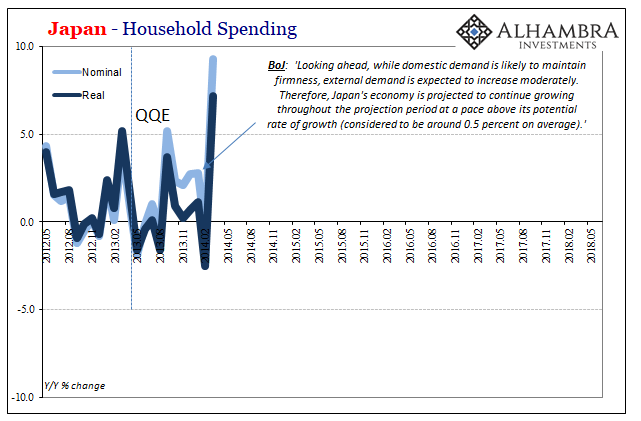

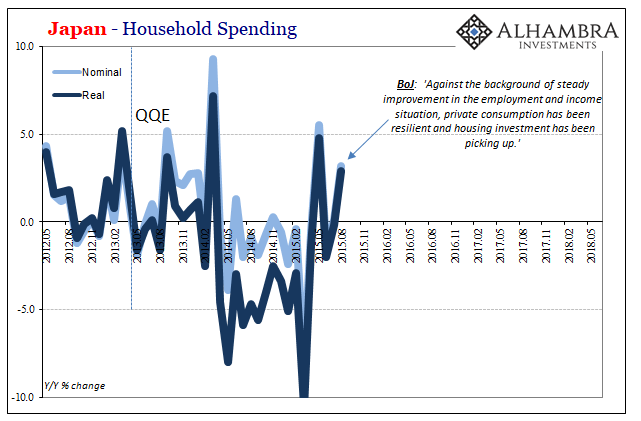

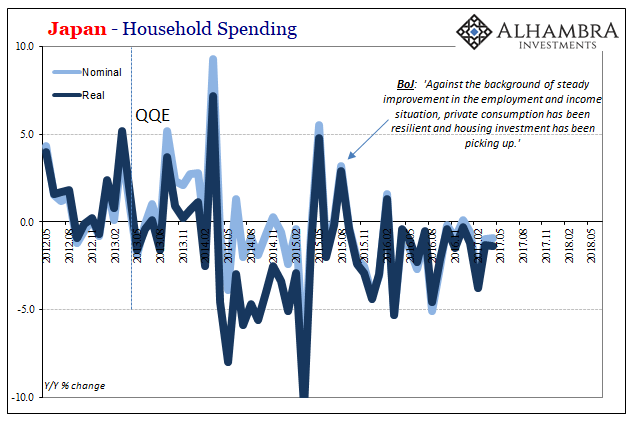

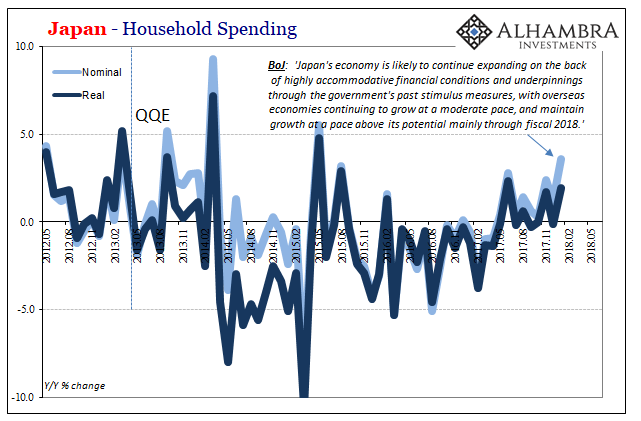

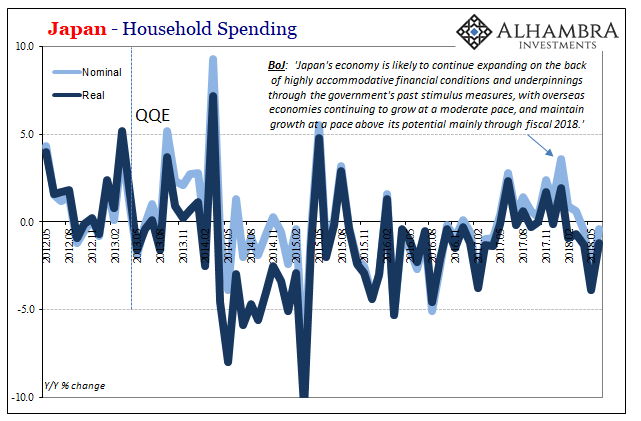

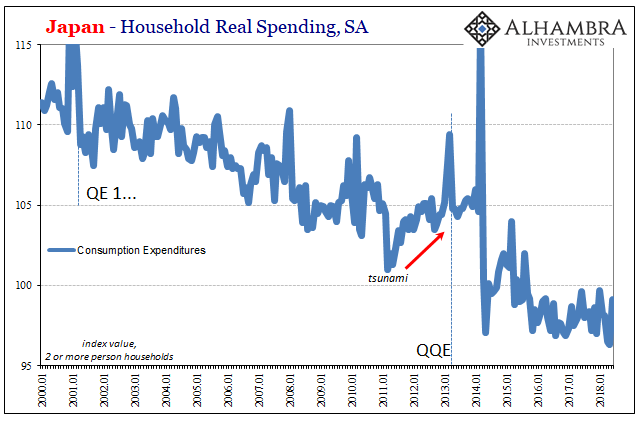

Using Household Spending estimates, we can reconstruct the same pattern in the 2010’s that we did for GDP in the 1990’s. Initially after QQE, spending rose particularly just ahead of the consumption tax hike. That was taken as a very good sign, as all jumps of this type always are, when it should have been heeded as a warning.

It wasn’t so that by 2015 based on nothing more than base effects from the 2014 collapse in spending (and self-delusion) so many positive expectations were formed out of basically nothing.

But that only meant when HH Consumption turned around in 2017 this was the one they had been waiting for.

In estimates released today, Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications reports that quite predictably Household Spending rather than accelerating or even expanding at nearly the same pace as late last year has instead contracted in each of the last three months through June 2018 – in nominal terms.

In real terms, Household Spending has now declined for five months in a row.

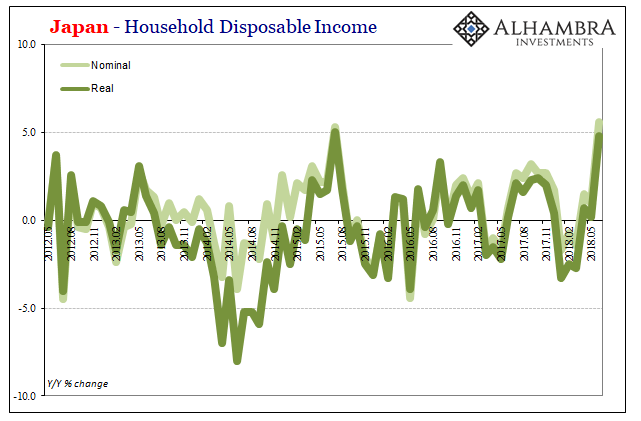

This is why today’s concurrent wage data is being touted. Japanese households have “unexpectedly” retrenched but rising income should mean something or other.

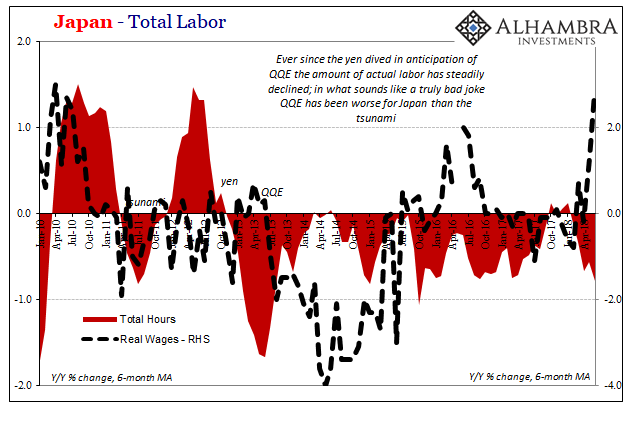

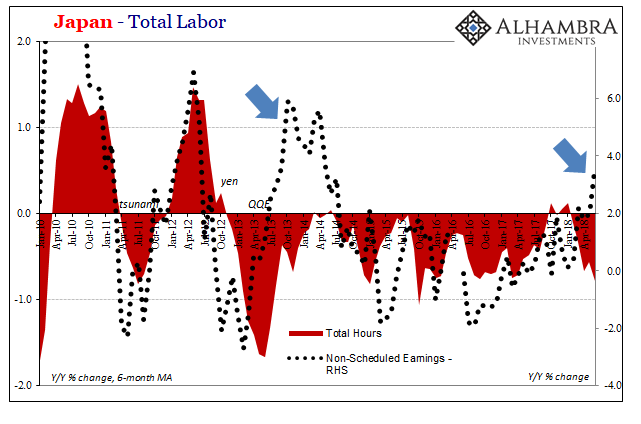

The increase in Japanese worker pay, however, comes with the same economic affliction attached. Total hours are again decreasing, meaning simply that Japanese employers are paying workers the same amount to do less. To an Economist, that might suggest an economic pickup, but to anyone who understands how a real economy (small “e”) functions this is not a good thing.

The Abe government has been after Japanese companies to raise wages for years, half a decade now. Japan Inc. responds by occasionally throwing out bonuses in lieu of scheduled raises and work. Again, it’s not quite the same basis for economic growth, real economic growth, where we would expect the opposite.

A real Japanese economic breakout would consist of rising hours and weak pay; exactly what was starting to happen in late 2017. Increased labor utilization would indicate actually rather than artificially growing demand, sustainable demand that over time would lead to rising incomes also on a sustainable basis.

As with a lot of things, however, 2017’s Japanese economic promise didn’t make it too far into 2018. Japanese employers are again cutting back on work as Global Reflation #3 quietly disappears but paying more to workers while they scale down again. Japanese workers, meaning household spenders, seem to realize what that will mean.

More than anyone else on the face of planet earth, they would know a false dawn when they see one.

Stay In Touch