During the decade of the seventies, there was an opening. The Bretton Woods system had largely failed in 1960, but gold exchange lingered onward until August of 1971. Long before President Nixon acted in defaulting on US obligations, however, global currency liquidity had increasingly been supplied through other means.

Those “other” means was an offshore ecosystem that though rudimentary compared to 21st century operations was every bit a global currency as the eurodollar of today. Dollars still dominated here but given the US’ economic and inflationary struggles there was an opportunity for others to exploit grave and growing worldwide dissatisfaction.

Japan seemed the logical choice to overthrow the dollar, even the whole Western-based paradigm. It was the growing Asian giant, the industrial powerhouse situated as the gateway to untapped Eastern markets. Japanese officials began preparations for a global yen alternative to the dollar by undertaking the necessary steps toward building an infrastructure. Not long ago I recalled:

For Japan’s government, though they may have been reluctant to relax regulations the figured it could be worth it if this represented the initial move toward a long-sought goal. There was, almost everyone anticipated, the opportunity particularly during that specific decade to turn the yen into a global currency.

Two years before Sears’ Samurai, the European Investment Bank had issued the world’s first euroyen bond. As with eurodollars, euroyen have nothing whatsoever to do with Europe’s modern euro. The term “euro” when applied to a currency simply means “offshore.” Thus, EIB’s 1977 float was a debenture denominated in yen but issued outside of Japan in Europe.

You can’t just up and replace one denomination with another. No matter how aggressive the Japanese became in the seventies and eighties, there was no real threat to the dollar from the yen. JPY would become a global reserve in some ways, but not really what everyone thinks when using that particular term.

In the wake of Japan’s 1990’s financial disaster, the Europeans next sought the same status. The European supereconomy paired with a supercurrency, the euro, was meant to challenge the dollar as the yen once tried. Predictions varied, but by and large it never really came to fruition, either. This despite the creation of what is a lovely bit of representative ridiculousness, the euroeuro.

We don’t really have too many ways of measuring the “popularity” of one currency over another. There are statistics that have been developed showing each denomination’s share of global trade. But that doesn’t equal the full weight of a true reserve currency.

Merchandise trade was the bulk of the matter in the 1950’s, an era when the British pound was still toward the top of the heap, but even London banks by then were already switching to the eurodollar. By the nineties, economic trade had become of secondary importance to what people still call “hot money”; the financial flows that often dictate the depth of groundwork that allows the global offshore system its reach and extent.

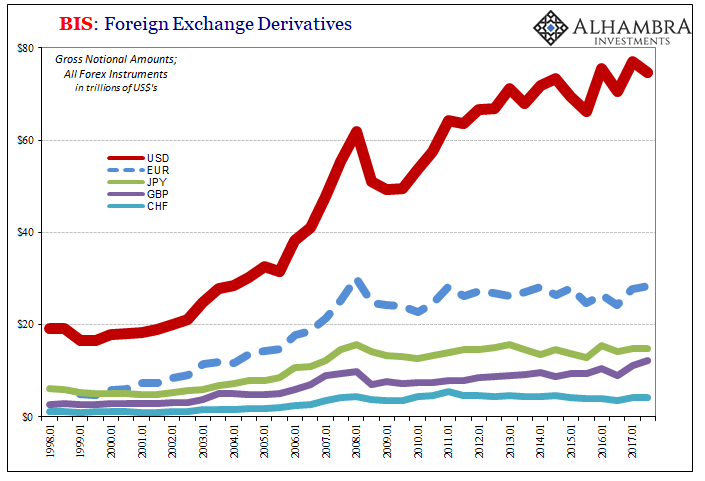

That leaves us with something the BIS’ data on derivatives to try and judge the penetration or dominance of currencies in this financialized world.

Two things stand out when looking at the question this way. One, the US$ remains on top by a large margin. Two, the whole system took a huge jolt in 2008 and never recovered. It started to in limited fashion but only up until 2011.

Both are consistent with other more detailed observations about the state of the eurodollar world, meaning the lack of alternative to it. The numbers bear out these distinctions.

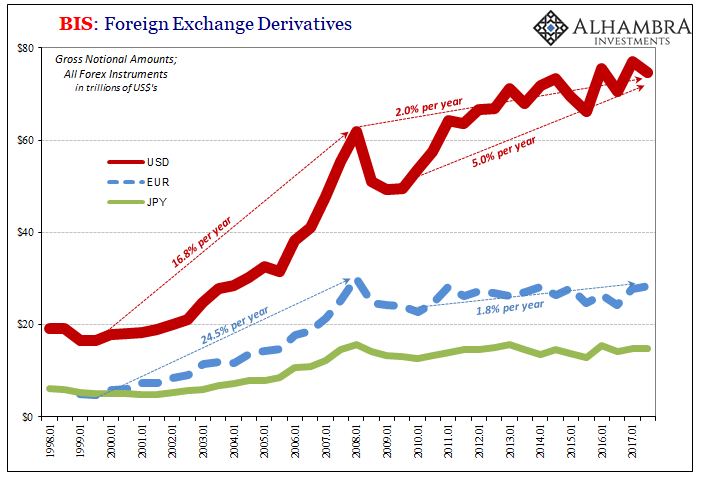

Going from near 17% per year growth in forex derivatives, using the US$, to just 2% after the panic is a wholesale change. It fits the definition of prolonged “tight” money and the related deflationary pressures.

Neither EUR nor JPY have fared any better post-crisis to challenge the eurodollar, to make good on the long ago promise of the euroyen or the twenty-year old boasting of the euroeuro. In fact, both of those have fared worse, at least in these terms of bank derivatives, during the last ten years (through the end of 2017).

That’s not really surprising given that what’s behind all of these currencies is the same thing, the very thing we wish to study and understand in all our monetary investigations – the bank or credit-based capacities of this offshore currency system. If banks suffer in terms of eurodollars, they would suffer in terms of both euroyen and euroeuro’s, too.

That they’ve stuck with eurodollars over either in the post-crisis era seems to indicate a rational choice about liquidity risk, among other factors (economic performance). The eurodollar may not be an ideal basis for a global monetary system as it may have seemed up until August 2008, but there is moderately less risk involved with it as the top piece than the others. It keeps the lights on. Euroyen? Maybe not even that much.

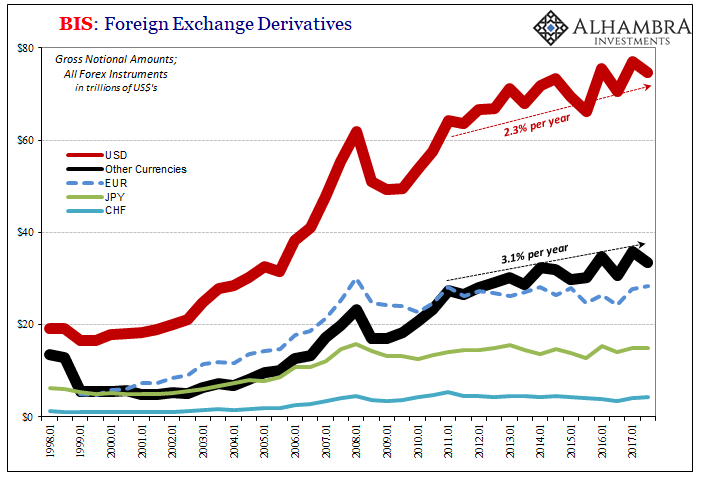

But there is another category in global forex derivatives. The BIS does us a favor in breaking them down by the largest currency denominations but excludes an important one from that list: CNY.

Instead, we are left to infer the popularity, or not, of China’s currency from its aggregation with other of the world’s currencies not specifically named. For me, the problem with this segment is that it is a micro-image of forex in US$’s, too immediately reflexive of US$ forex notionals. That would seem less other currencies in use for their own sake and instead some kind of intentional counterbalance to the dollar still on top.

Even if we assume that all of “other” related to CNY, which isn’t anything close to realistic, again there isn’t a challenge to the eurodollar out there among these “footnote dollars” that would be absolutely required of any challenger. Since the 2011 crisis, or eurodollar event #2, there is nothing to indicate a growing preference for something else.

The year 2011 is significant for other reasons, too. That year brought not just the second and fatal breakdown in global credit-based money, it was also the year the Chinese first declared RMB set to do what it hasn’t done.

On March 2, 2011, the PBOC announced its intentions to vastly expand renminbi’s cross-border reach. Like Japan of the 1970’s, the Chinese knew it would take some considerable effort to implement the necessary depth (below taken from Google translate).

Continue to implement the work of overseas relevant institutions investing in the inter-bank bond market and actively respond to the demand of foreign currency authorities to include the RMB in their foreign exchange reserves.

Quite predictably, the Western media was ablaze at the political ramifications. China was going to replace the dollar, many said.

Other moves on the part of China to internationalize its currency include allowing foreign companies to issue yuan-denominated bonds and relaxing rules for foreign financial institutions to access the yuan.

Aside from the efforts of the Chinese government, fundamentals also point to the increasing international popularity of the Chinese currency.

“Increasing popularity” can mean many things, and in this case it almost never means what the people using it intend for it. There really isn’t much indicated appetite for CNY outside of places like Iran, Russia, and Pakistan. Even in Africa, there is more regret than eagerness for One Belt One Road (a topic which I’ll expand on at a later date).

Like yen during the Great Inflation, the eurodollar breakdown and deflation of the last decade has opened the door for an alternative. Yet, none has materialized. China’s “big news” was seven and almost a half years ago. If they could’ve, they would’ve. Instead, they are as locked into dollars today as they were at that point, if not more so.

That’s ultimately the point that gets lost in everyone picking sides. There is only one side. The Chinese and the euroyuan ran into the same issues (including Hong Kong) as the euroyen and euroeuro, the same thing that plagues the eurodollar. It’s a credit-based system meaning that what needs to be done is not replace which denomination with what other inside of it. The whole credit-based foundation needs to go first.

I know, I know. That’s what the Chinese are up to, supposedly. They are buying up all the world’s spare physical gold in order to recreate the 1880’s. As if that was any more realistic.

Infrastructure (and architecture) matters, which is the one reason why the eurodollar survives where long ago it shouldn’t have. Right now, it doesn’t grow and it presents the global economy with myriad desperate fundamental challenges, but there just isn’t anything else. And with most Western authorities truly trying to believe in a global economic boom right now, there won’t be anytime soon.

Stay In Touch