On November 7, 1973, President Richard Nixon addressed the nation via a broadcast television appearance. The topic wasn’t what you might think. Rather than trying to reassure Americans about the unfolding Watergate scandal, Nixon instead attempted to encourage the country about its energy situation.

The month before, Egypt and Syria had launched a surprise attack against Israel. Arab members of OPEC intended to punish any nations in support of, or even just perceived in support of, the Israelis during what would be called the Yom Kippur War. The United States was targeted as was Canada, the UK, Japan, and even the Netherlands.

Nixon told Americans that the government was forecasting at least a 10% shortfall in crude supplies, maybe as much as 17%. The country hadn’t seen anything like it since the rationing of World War II.

Now, even before war broke out in the Middle East, these prospective shortages were the subject of intensive discussions among members of my Administration, leaders of the Congress, Governors, mayors, and other groups. From these discussions has emerged a broad agreement that we, as a nation, must now set upon a new course.

Though it was peacetime for the United States, Nixon encouraged cutting back, a new paradigm of rationing. As he said, in the short run “it will require sacrifice by all Americans.”

He then set about a long-term goal on par with the Apollo Program and the Manhattan Project. The President called it Project Independence, in keeping with the spirit of the “Bicentennial Era.” Trying hard to resurrect the spirit and enthusiasm of Kennedy, Nixon declared that by the end of the decade the US would “meet our own energy needs without depending on any foreign energy sources.”

So began the age of energy independence. As with most things related to Nixon, it didn’t come close. Even today we still import a massive amount of crude oil. The shale revolution of the past half-decade has brought this country closer than at any point to realizing that goal, if forty years behind schedule, but we aren’t quite there yet.

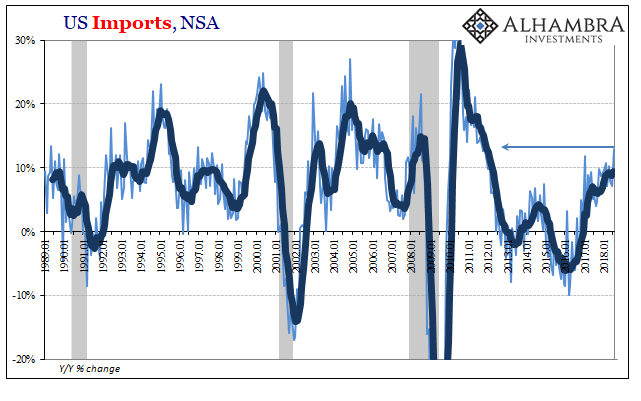

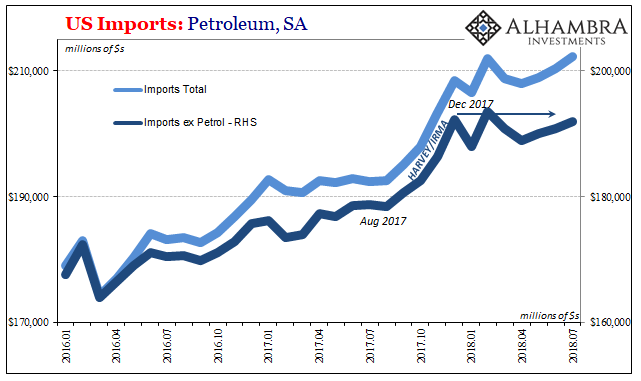

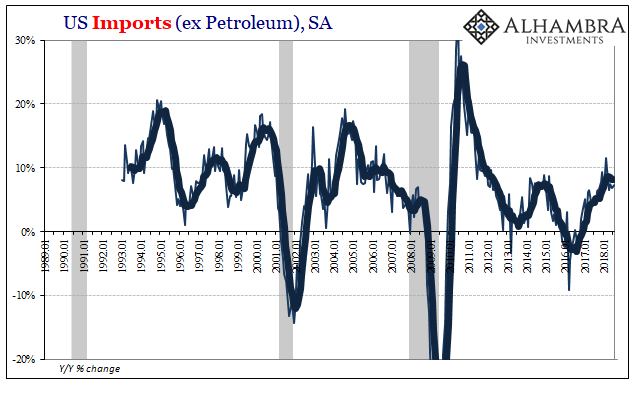

Since the downturn in 2015-16, imports have been rising again as reflation had taken over from deflation. A non-negligible portion of the increase off the bottom has been due to oil imports, specifically paying more for them. As oil prices have risen, imports look better from the standpoint of US demand for goods.

In July 2018, according to today’s report by the Census Bureau, total US imports including petroleum rose 13% year-over-year. That’s the highest growth rate since September 2011. There are questions about that figure already in the context of “trade wars”, as in a temporary boost to US trade as producers and wholesalers attempt to game the potential tariffs and restrictions.

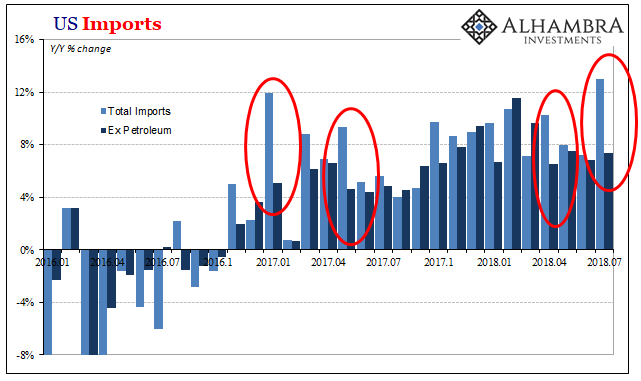

In these updated numbers, however, there doesn’t seem to be too much of that. Instead, almost half the annual gain was due to oil prices. Imports of crude oil were up 50% from July 2017. Ex petroleum, imports rose only 7.3% year-over-year.

Outside of oil, imports have been down slightly since the end of last year. The Census Bureau estimates in the months of 2018 following the clear boost in 2017 in the aftermath of Harvey/Irma, non-crude US imports have fallen from a seasonally-adjusted level of $193.5 billion to $191.9 billion in July.

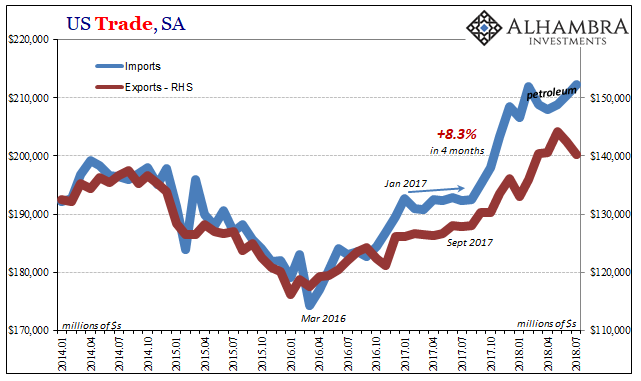

This energy price skew has contributed mightily to the trade deficit. The merchandise shortfall in July (not seasonally adjusted) was nearly a record, -$72 billion. The record for it was reached earlier this year, in February, where the country posted a nearly $76 billion deficit for just the one month.

On the other side of the ledger, export growth cooled off in July contributing its part to the trade disparity. Unadjusted, exports rose 9.3% year-over-year. In seasonally-adjusted terms, exports fell rather sharply perhaps indicating the outbound side of pre-trade war participation (retaliatory tariffs) running its eventual course.

In pure macro terms, these aren’t the numbers for a booming US economy. On the contrary, they suggest the same sort of stagnant demand that has kept the global economy in turmoil since 2011. Following a downturn like the prior one, US demand for non-petroleum goods should be rising between 13% and 18%, not 5% to 8% with the aftermath of huge tropical storms contributing all the difference between 5% and 8%.

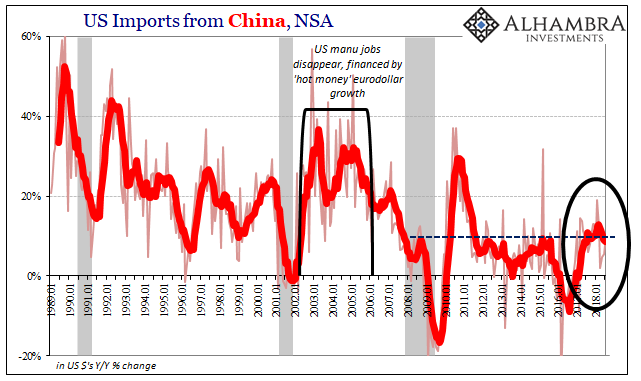

As always, we can turn to the Chinese for their assessment of US economic conditions. Just like 2014, they must vehemently disagree with the current mainstream appraisal. Hardly a boom, Chinese imports into the United States increased by only 8% year-over-year in July. That’s down from a peak of 19% in February when uncertainty about President Trump’s policies pushed an obvious surplus of goods in this direction.

The six-month average for the growth of Chinese imports, which still includes February, is now down to just 8.6%. That’s about one-third to one-quarter of what Chinese manufacturers had been counting on in the past as actual growth.

If hurricanes and tariffs can’t help China hit even 20% let alone 30%, there’s only a serious shortfall in US demand rather than a booming economy.

Likewise, if it takes tropical disturbances and oil prices to get total imports up a little more than 2014 it isn’t a good sign of domestic economic strength. The issue isn’t trade wars nor really crude imports. As it was for Nixon, the problem is really (euro)dollar.

Stay In Touch