By the time Shinzo Abe had been elected, he already had the wind at his back. At least it could have been described that way by Economists. While Abe was given a second chance at being Japan’s Prime Minister in the middle of December 2012, his government found the yen and stock market moving in his direction. These are called “tailwinds.”

But are they?

Japan’s an interesting case study in whichever factor you might research. Been there, done that. And yet, it’s as if in the mainstream of Economics the island nation is some far off, desolate island. Japan’s economy may be mired in a thirty-year slump, as if that could somehow ever be normal, but it’s not been completely disconnected to everything going on around it.

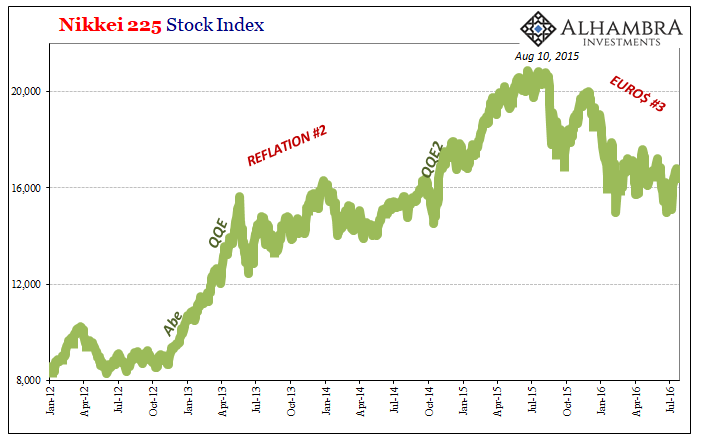

By the time Prime Minister Abe officially put forward the three arrows of his Abenomics, the Nikkei 225 was on fire. With polls prior to the election showing the inevitable, and the yen already moving lower in anticipation, stocks had been up sharply for more than a month before any votes had been cast.

And that was six months or so before QQE, the first so-called arrow, would begin. Thus, once again, quantitative easing isn’t money printing; but, as I often write, central bankers are delighted if you think it is. In other words, stocks are portfolio assets, meaning that they are bid out of savings far more than any new money additions.

In the central bank paradigm, it is all about expectations. These are assumed rational, but these kinds of stock market reviews make you wonder.

It wasn’t QQE and “money printing” that pushed the Nikkei off its low levels. Rather, investors were bidding (reallocating savings) in anticipation of it. Whether or not people believed it was going to be that is debatable, for many it wasn’t about the level of bank reserves specifically but the clear commitment from the Bank of Japan to, borrowing from Mario Draghi, do whatever it took to get Japan’s economy moving again.

Therefore, things started to move in that direction long before anything could move at the BoJ.

That specific stock rally was exhausted by the time QQE actually began (apparently, it didn’t the “money” that QQE would “print”). It wouldn’t be until October 2014 that the Nikkei would make a second push up to and above 20,000.

Again, expectations. People are taught that these things work, that central banks are powerful enough and what was missing in Japan up to 2012 was the will to use that power. Pace Paul Krugman, the Bank of Japan under Abe would no longer fear the consequences of being truly reckless. That was, in the end, the whole point.

And yet, by October 2014 there were already signs it wasn’t working. If you have to up QQE, as BoJ did at the end of that particular month, it couldn’t have been truly reckless.

Stock investors didn’t really care, though. They reallocated even more savings in the wake of QQE2 despite what were emerging “headwinds.” These were local in the form of the VAT tax hike earlier in 2014, but even that didn’t stop the Nikkei. It wouldn’t be until the days after August 10, 2015, that Japanese stocks would be rudely interrupted from their perverted views on Abenomics.

What happened in August 2015? It wasn’t anything purely Japanese.

No matter how committed the BoJ might have become in that time period, eurodollar shocks were more than enough to question if not the commitment than at least the results. There aren’t many direct monetary inputs into global stocks any longer, not since the thirties. But there are some and they typically relate to leverage on the downside (including repo done on stock collateral, which isn’t a huge part of either business).

What that means is that these intermittent eurodollar disruptions are direct consequences of liquidations brought about by the deflationary sequences associated with monetary disturbances. More than that, though, it is these times when the failure of expectations regimes is most clearly visible.

You are willing to give central banks the benefit of the doubt when things are generally positive if still lackluster. If conditions are no longer even lackluster? Not so much. Thus, deflation in stocks, moving mostly through expectations, isn’t a clear process.

That much was proven in January 2016 when BoJ went one further step into wildness. They brought out NIRP and rather than reassure everyone about the central bank’s commitment to do whatever needed to be done, instead it proved things were going the wrong way despite them. Top to bottom during Eurodollar Event #3, the Nikkei shed more than 28%; not because Japan’s economy was going to be hit especially hard by the cresting deflationary wave, and it wasn’t, but because for the first time since Abenomics there was no getting around the powerlessness of it.

Obviously, this is a global issue and not really specific to just Japan. Each domestic system adds its own flavoring to what is a worldwide agenda. The Japanese spin on these eurodollar events is therefore especially compelling.

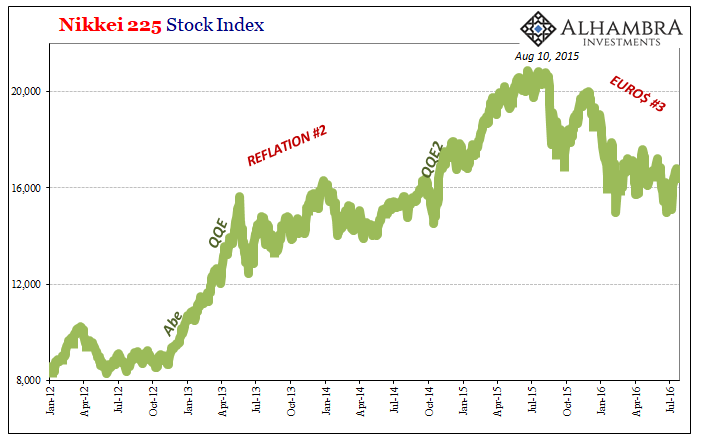

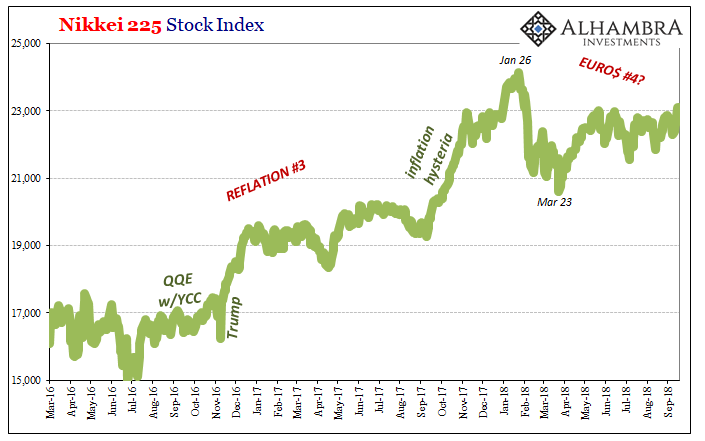

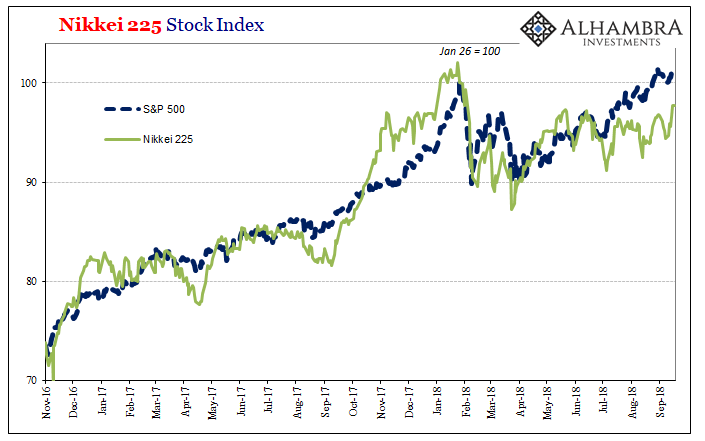

So, let’s look at the first chart above and then add to it one for the current cycle. It does look awfully familiar.

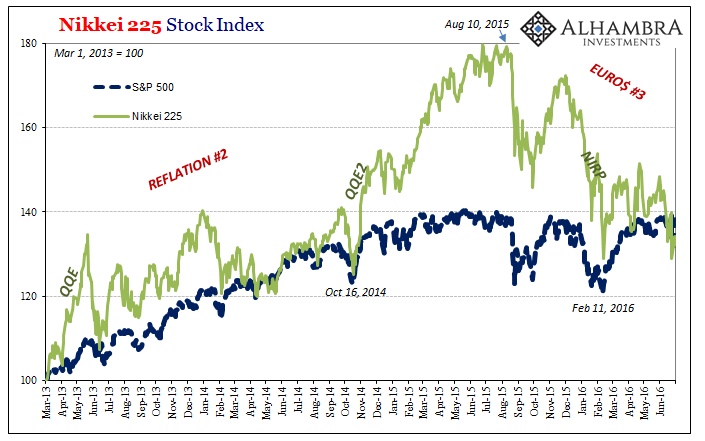

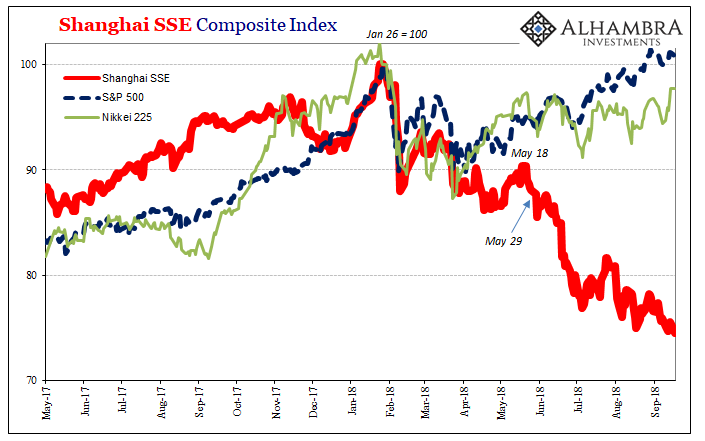

The dimensions are different but the pattern is a near mirror. I think Japan helps us understand the dispersions in performance since the clear eurodollar interruptions that registered everywhere in late January.

Expectations, not money printing one way (QE, QQE, QQE2, QQE w/YCC) or the other (QT). Since January, these three major stock markets have largely gone in separate directions. Before, they were all moving higher together. For two months, they all moved together lower and by nearly the same amount each one.

US stocks have outperformed since the end of March/early April; Japanese stocks have been in the middle. At the bottom, by a lot, Chinese markets are really struggling.

Many will attribute the differences to “trade wars”, as in these markets are expecting the US to win them at China’s expense. Perhaps, but I doubt it. We’ve seen these cycles before and there were no tariffs or NAFTA renegotiations in 2014 and 2015.

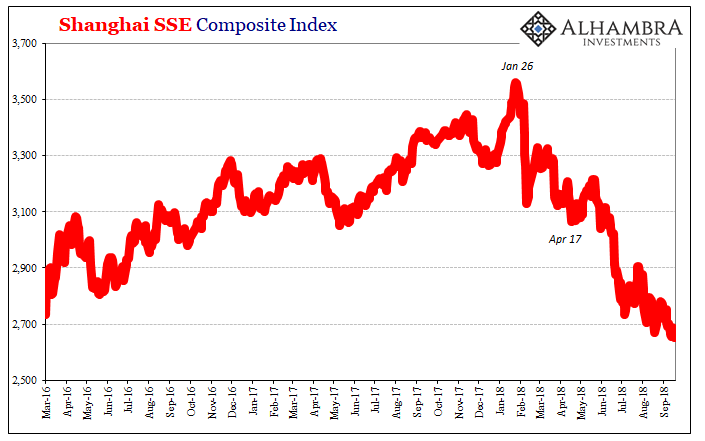

Back then, it was the other way around up until August 2015. Chinese stocks were way outperforming on the upside, far better than even Japan’s. Everything has since been turned around because that’s where eurodollar event #3 hit the hardest – EM Asia.

Going back to expectations, in China there isn’t much to lift them in 2018. The PBOC is fighting and losing. There is no longer an appetite in the vast government sector for any “stimulus” fiscal or otherwise. Economic deceleration after very little recovery from the last dollar event is already apparent and broadening. Any trade dispute comes in at the end of a long list of negatives.

In the middle is Japan. This year might be the one where you can say China isn’t Japan and it means a positive for the latter. The BoJ isn’t getting where it wants to go, but at least stock investors (clinging to the myth of QQE) still have the Japanese central bank doing something. The monetary events earlier in the year were alarming, to be sure, but it’s not really clear unlike in China what that might mean; Japan fared relatively well during the global downturn of 2015-16 if for no other reason that it was already scraping along the bottom anyway.

At the opposite end is the US. January and February liquidations shook the US markets as the others, but these have been slowly but steadily shrugged off and dismissed. Eurodollar Event #4 seems instead like some distant overseas turmoil that can’t possibly penetrate this booming economy. Memories of 2015 and 2016 have already faded because in most peoples’ minds Janet Yellen was right about “transitory.”

But US investors are at least nervous about it because the correct term wasn’t transitory it was, and is, intermittent. This may be the one time when, like the Nikkei in 2014, relative outperformance is the least desirable attribute.

Investors allocate their savings to stocks based largely on their views of whether or not central banks will be successful. And those views have been shaped, consciously or not, by an outdated worldview that equates monetary policies, especially those that are non-standard, with money printing. It becomes perverse toward that end; people buy stocks thinking QE is money printing, stocks go up confirming for these people that QE was money printing.

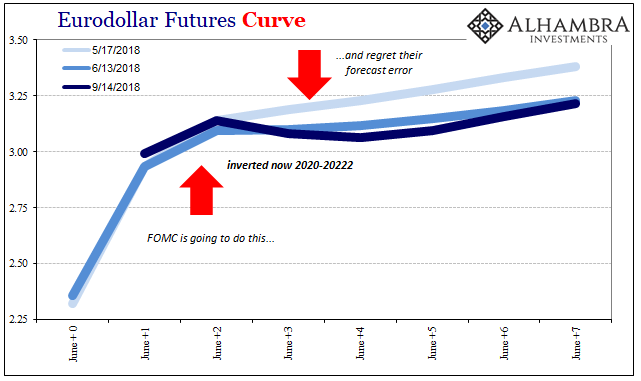

What happens when expectations aren’t met? That’s what each eurodollar disruption has meant in stocks; variable challenges to the same types of expectations bound together by a common baseline. Up to now, central banks have responded to them by promising to do more, to up the ante even further. And stock markets have, after enough time in disarray, obliged these promises.

Is 2018 different?

In one way, yes. For the first time in a decade, central bankers are now saying they won’t have to do more. They’ve figured it out, they claim. And it is in the US where this change is presumed furthest along (“rate hikes”).

What happens if/when these market expectations meet a fourth setback? That’s the question.

Stay In Touch