You never quite know what you’re going to get with each monthly update. High frequency data tends to be noisy anyway, more so in the more exotic series. Following a month where something really changes, however, you aren’t quite sure if it will turn out to be nothing more than a phantom. Does last month’s big number get revised down or even away? Or does it stick around for a second month and suggest there was something really going on?

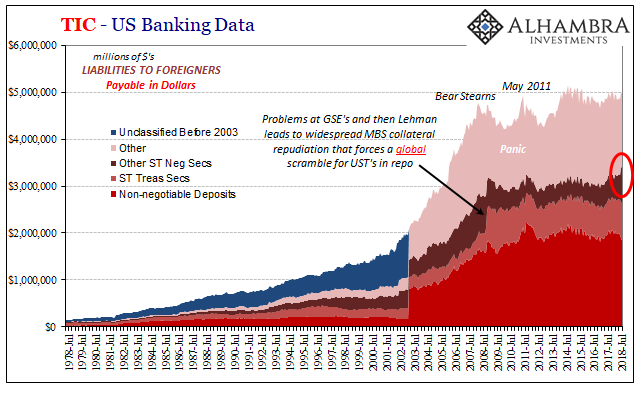

The TIC figures for June 2018, released last month, were eye opening. It wasn’t surprising that the data picked up on something. After all, May 29 wasn’t the usual trading session in global bond markets. By bond prices alone we knew it was a collateral call. We just couldn’t tell how much of one.

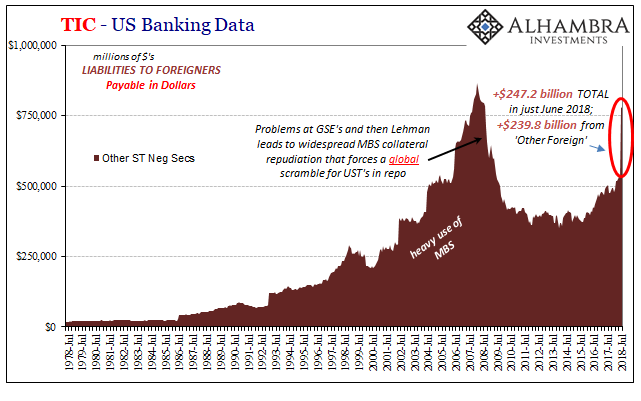

It had to have been sufficiently large enough so as to cause, and sustain, reverberating effects, ongoing ripples throughout the eurodollar system. The scale was unexpected, in the TIC view of it. The estimates for June suggested about $200 billion in collateral changes (as noted last month, leaving us more than questions than answers). Was it a statistical quirk, or would it survive revisions?

Not only did it remain in place for July, the collateral quake in June was revised upward. That is, whatever it ultimately was on May 29, this disruption maybe even dislocation was even bigger than originally calculated by the good folks at the Treasury Department.

The first run of June numbers intially put it at about $178 billion. These updated numbers now suggest an astounding $247 billion. There’s just nothing like it.

Very little changed in the estimates for July, the latest month, meaning that whatever happened following May 29 stayed with the system for another month further on. That wasn’t unexpected.

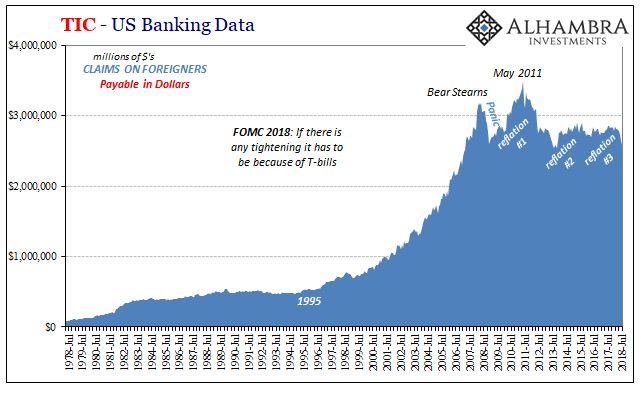

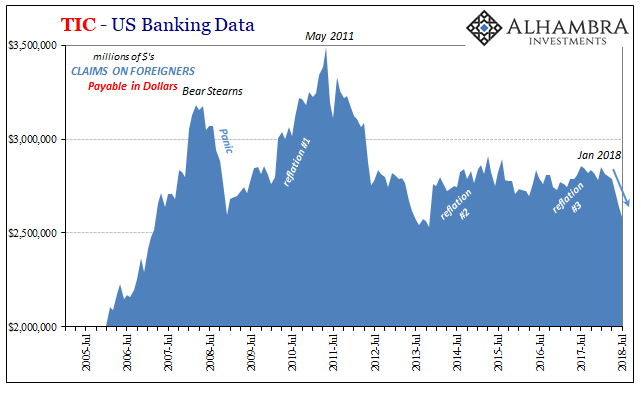

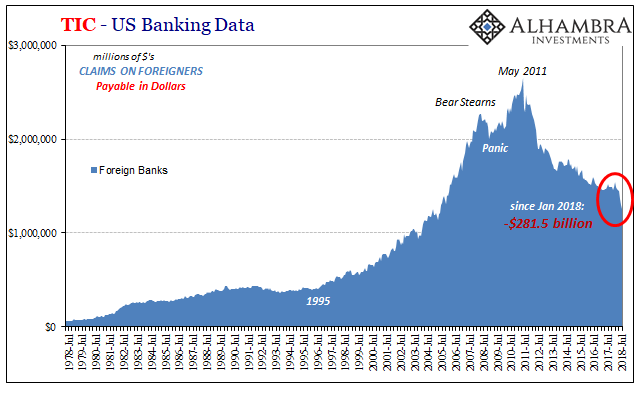

Nor was the additional data pointing out related negatives propagating throughout other parts of the vast eurodollar system. On the “blue” side of the ledger, where US banks lend dollars and collateral overseas, there was another large retreat particularly against foreign bank counterparties. Small wonder, what with May 29 having shaken the system so deeply; a quarter-trillion deep.

Since January, when the liquidations in stocks first struck, US banks report almost $300 billion fewer claims on foreign banks in short-term money instruments. Obviously, these six months represent a sharp change in trend even though the prior trend has been since May 2011 persistently lower.

“Something” happened which accelerated the withdrawal; FOMC officials and other central bankers really, really want to believe it was all President Trump’s fault with his T-bills.

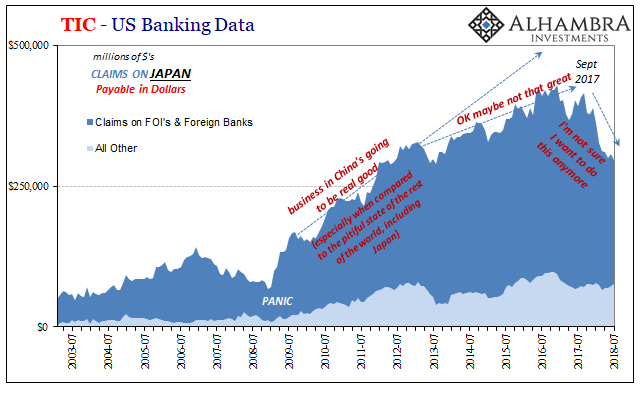

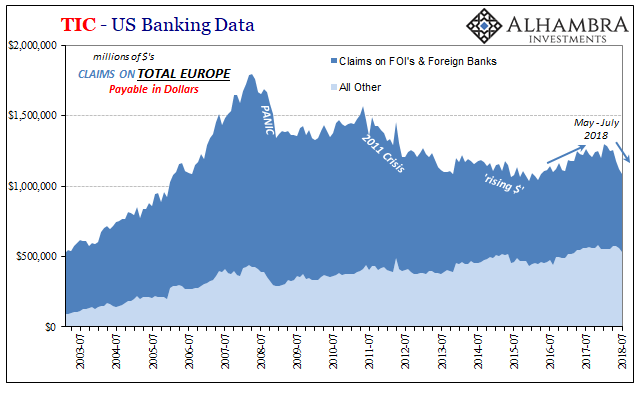

Given the wealth of data provided by these TIC estimates, we at least have some idea where these things are happening if not quite yet exactly what they are. In terms of geography, Japan and Europe.

The Japanese withdrew in disruptive fashion in both January and February, accounting, I believe, for a lot of what happened in those two months (in particular those two weeks starting on January 29). They were followed to the exits starting in May by European banks (bunds).

Again, this isn’t a surprise given what the euro started doing in that month. The sharp fall in Europe’s currency exchange against the dollar told us already that Europe’s banks were reversing their reflation participation in the eurodollar system. It wasn’t all that much to the upside during Reflation #3, but even still any small change was going to be a problem. Since April, it has been a full-fledged retreat.

The EM massacre makes a lot more sense, unless, of course, you are an EM central banker.

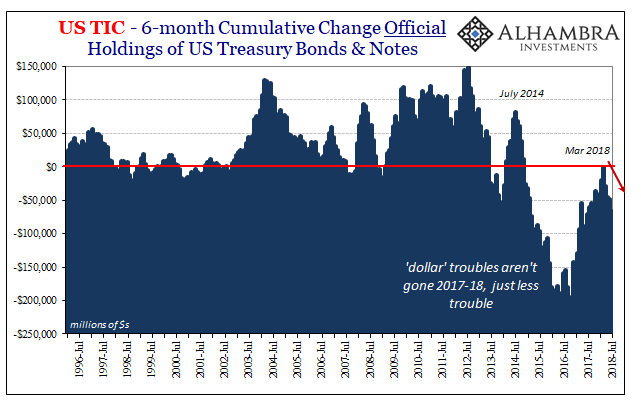

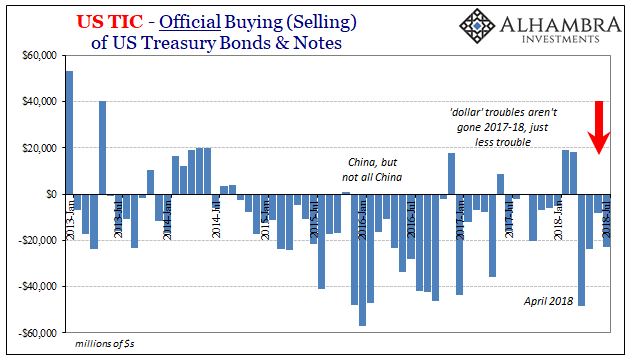

One other change to a trend has also become more apparent with the update for July. With the eurodollar system descending once more into another global deflationary squeeze, foreign central banks have had to revisit “selling UST’s.” With conditions really deteriorating in April and May, official “selling” has increased to levels more like 2015 than 2017.

And like 2015, it hasn’t been successful. The reason is often pretty simple, typically relating to a misdiagnosis of the problem due to all central bankers using the same Economics textbook devoted to statistics rather than serious study of money and economy.

The official sector intervenes, “selling” or otherwise deploying their holdings of securities in order to calm increasingly hostile funding markets for these offshore dollars. They do so, however, on the belief that any disruption is temporary; it would have to be given what the Economics textbook says about the Federal Reserve’s QE additions to US$ bank reserves as well as its “highly accommodative” interest rates.

Apparently, also unsurprisingly, foreign officials learned little or nothing from their experience in 2015. Having accepted Janet Yellen’s “transitory” factors fantasy, they were once again wholly unprepared for what has been entirely too familiar. Thus, Banco and its criminally embarrassing June actions (as well as a bunch of others performed by those central banks outside Brazil).

Even on a day like today when US wage euphoria remains the dominant theme, there are signs (curves) that the banking sector hasn’t just forgotten May 29 (as well as a bunch of other actions). Nothing goes in a straight line, though officials will continue to act like May 29 never really happened. Just a bunch of mispriced bonds, they’ll say, without once checking the Treasury Department data.

Stay In Touch