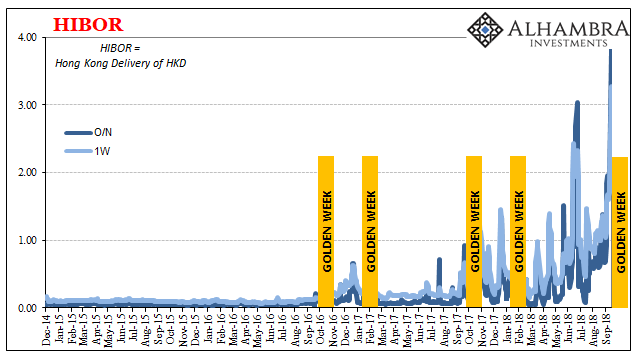

It’s that time of year. September, the leaves start to turn and the air grows crisp. Autumn smells arrive; the Chinese prepare for their nationalist Golden Week. Ever since 2014 and the dollar’s rise, that is, eurodollar tightening especially in Asia, these holiday bottlenecks are never boring. To be shut down for an entire week in early October, the banking system in China builds up a liquidity stockpile in September.

There were actually three Golden Weeks up until 2007. The middle one, surrounding Communists’ infatuation with May Day, was quietly dismissed on the recommendation of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). These long holiday breaks were being viewed as disruptive to economic flow.

In September 1999, the State Council devised the original Golden Week holiday system as a way to standardize vacation time (Communists’ infatuation with sameness, which is very different from equality). It was also intended to boost tourism and economic activity. Economists are the same whether Communist or Western; they all think they can increase spending by changing the most arbitrary factors.

The biggest factor in the December 2007 elimination of the third week was obvious interruption. Cai Jiming, the project leader for the CPPCC in 2007, told government officials that (translated):

There are data showing that since the implementation of the Golden Week Vacation system, the pulling effect on consumption has not been great, but it has brought a series of negative effects, such as increasing short-term costs for businesses, declining service quality, and increasing government public management costs.

China’s National Tourism Administration agreed, so on December 16, 2007, the Chinese Central Government announced a revised Regulation on Public Holidays for National Annual Festivals and Memorial Days. There would now be just the pair in China, two economic disturbances better than three.

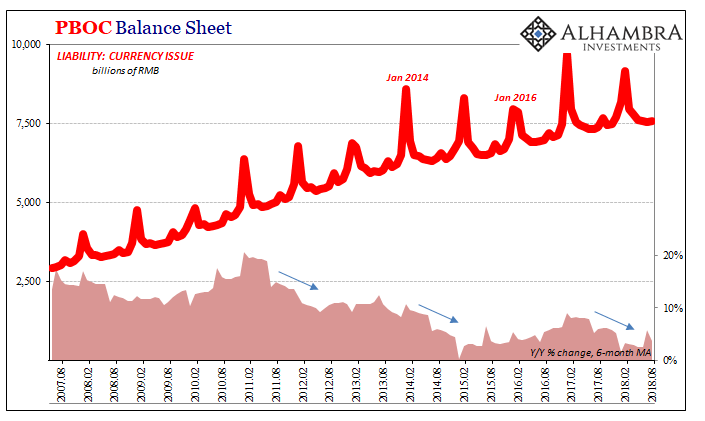

The banking system felt them as much as the real economy, but adjusted well enough. When money was plentiful, no big deal. But as things have really tightened the last four years, the Golden Weeks have become eventful. China’s weeklong New Year every January has tended to be the greater of the two, but October’s celebration of the Communist takeover has contributed its share of interesting behaviors.

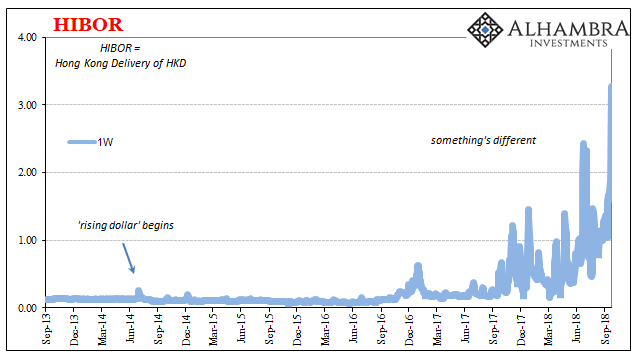

These haven’t been limited to mainland China. Tightening and volatility ahead of the October festival has been witnessed in Hong Kong, too. It’s one of the most obvious changes to the interconnection between CNY and eurodollars.

September 2018 has taken it one step further still.

The overnight HIBOR rate, the cost of borrowing Hong Kong dollars unsecured by collateral, spiked higher nearly two weeks ago – right on schedule. On September 13, it was almost 2% and remained at that elevated level through yesterday. Today, the overnight rate fixed at nearly double that, 3.85%.

The Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the city’s currency board, which has acted as a de facto central bank this year given what’s happened with HKD, refused to comment publicly. They would only note privately, in emails obtained by several local media outlets, that “market participants” were watching “elevated interbank rates.”

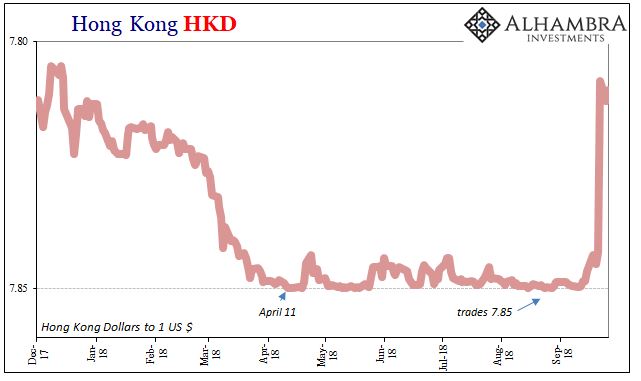

They would have to given what’s happened to the currency:

A reverse from the bottom range of the allowed band should be a welcome sign to Hong Kong’s beleaguered monetary officials. The HKMA has really struggled this year in ways it wasn’t expecting.

But a surge all at once isn’t what anyone in Hong Kong wants to see. Volatility is always and everywhere the real killer for anything in the banking system. It doesn’t discriminate. Risk perceptions were already challenged by HKD’s sharp decline earlier this year.

As a technical matter, the dearth of liquidity in the city has apparently brought a rush of funds into the area to take advantage of the surge in rates – HIBOR though unsecured being viewed universally as still at least a low risk if not as before completely risk-free. Near 7.85, sure. But all the way to 7.80?

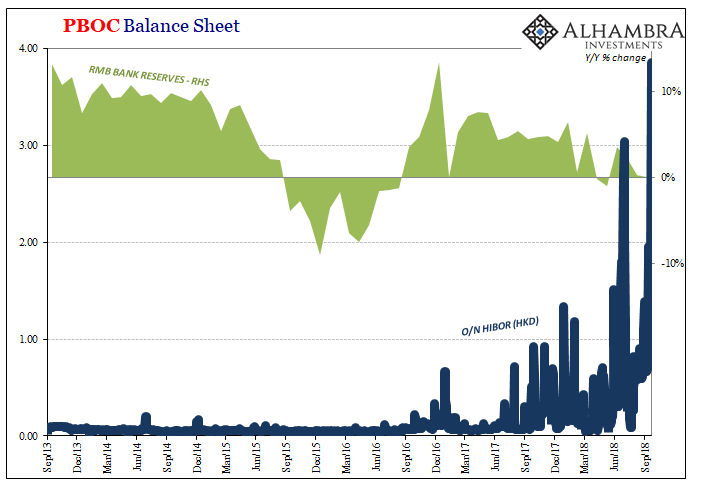

The real question is where those funds are coming from. There haven’t been any similar moves in any major currency partners, especially CNY. The closest thing has been the euro’s rebound, though it began back in mid-August (with CNY’s stabilizing).

Instead, we are left to suspect China’s latest approaching Golden Week. Banks in the hoarding stage can only become more desperate if hoarding is hard to accomplish. These holidays have always been disruptive, but the last few years they are really pushing it.

“They.”

Stay In Touch