On December 8, 1940, Winston Churchill wrote to Franklin Roosevelt. The situation was indeed grim, France having fallen to the Germans and the United Kingdom pushed right off Continental Europe. Defeats in the Pacific were some of the worst in the long history of the British Nation. The battle was now raging over English skies, the island isolated in every conceivable way.

The primary purpose for the British Prime Minister’s communication to the US President was money. He had run out of it. Without some form of desperate aid Churchill knew they were finished.

The moment approaches when we shall no longer be able to pay cash for shipping and other supplies. While we will do our utmost, and shrink from no proper sacrifice to make payments across the Exchange, I believe you will agree that it would be wrong in principle and mutually disadvantageous in effect, if at the height of this struggle, Great Britain were to be divested of all salable assets, so that after the victory was won with our blood, civilisation saved, and the time gained for the United States to be fully armed against all eventualities, we should stand stripped to the bone.

Not many Americans agreed. Before Pearl Harbor, the US attitude was very different. Americans had had enough of European wars. Constant strife wasn’t a 20th century invention. For all their lives, people in the US had been reading and hearing about European battles and conflicts. They occasionally participated.

At the outbreak of WWII back in September 1939, the US Congress passed the Neutrality Act which FDR signed. Britain or any other willing belligerent could buy war materiel from US companies but only on a cash basis. The United States wouldn’t play favorites; if you had the money you could buy the goods.

The Johnson Act of 1934 had already made it illegal to offer credit to those nations still in arrears for the first big war. The US had lent huge sums to the UK in the teens, and they still hadn’t paid up by the outset of the second one.

Things began to change in September 1940. FDR agreed to “sell” 50 old WWI era destroyers to Britain in exchange for 99-year leases to bases throughout the Western Hemisphere. The President could then sell it to the public as an American defense initiative serving two purposes – protecting domestic interests as well as aiding, in a small way, the British war effort without making them pay cash for the help.

It would pave the way for what became known as lend-lease; the US would supply an abundance of arms, medicines, and basic necessities in exchange for future rights. In Article VII of the treaty signed by the US and UK, those future rights consisted of a joint effort in writing and constructing a new liberal international order – once they finished off the warring Japanese and Germans and counted the tens of millions dead.

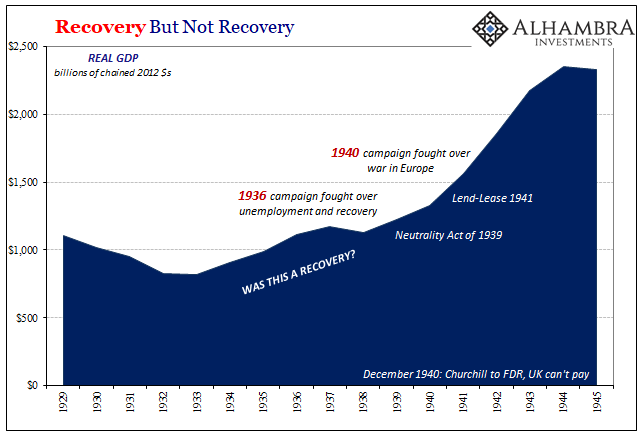

For many people, we have been taught this is the moment the US came out of the Great Depression. Britain’s near devastation and near destitution was America’s great opportunity. Or something.

Perhaps, but one thing is inarguable. Until 1941, the Great Depression was still a depression. An entire decade had been lost, and indeed had contributed the very climate into which full-scale war might be triggered.

According to modern estimates, in 2012 dollars no less, US real GDP expanded by 8.0% in 1939 and 8.8% in 1940. Those were rates that were consistent with the prior “recovery” which wasn’t. In 1941, as lend-lease removed all cash constraints from US service to the British, GDP soared by almost 18%.

No matter how you might characterize it, what happened to the US economy in the first half of the forties wasn’t growth, either. The utter destruction of so much of the world belongs to the legacy of the thirties, not the starting point for the definitive postwar prosperity that would follow.

Yesterday, former Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson visited with FoxBusiness Channel to sit down for an interview (thanks T. Tatteo). Known as Hank, Paulson wasn’t some obscure former cabinet officer whose tenure was uneventful and forgettable. Rather, Hank happened to be in charge of the literal printing press during the 2008 panic and meltdown.

“I think we can look back on it,” Paulson said Tuesday during an exclusive interview with Maria Bartiromo. “And while recognizing how difficult it’s been for so many Americans, recognize it could have been far worse, because we were very close — very, very close — to a real economic catastrophe that could have rivaled the Great Depression.”

Hold that thought.

That’s the problem with these guys. They all write the economic history as if it began with “jobs saved.” These are not separate issues, the contraction from recovery; or lack of recovery. If the economy never comes back, then it doesn’t really matter how deep it was at the worst point, does it? Time is absolutely conclusive.

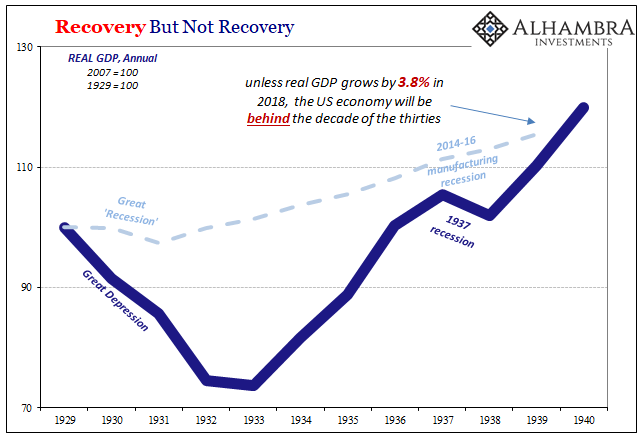

Should real GDP in the US fail to reach 3.8% in 2018, this economy will have officially underperformed the 1930’s. Let me repeat that. Unless GDP grows by near 4% for the entire year and not just the one occasional quarter, we have grown by less than during the decade that followed the 1929 crash.

This is their “boom.”

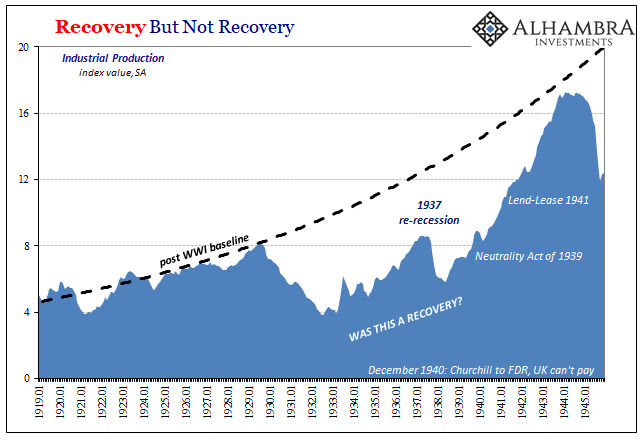

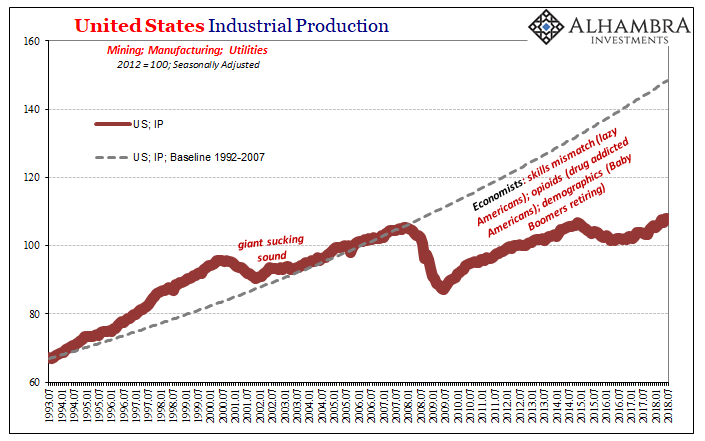

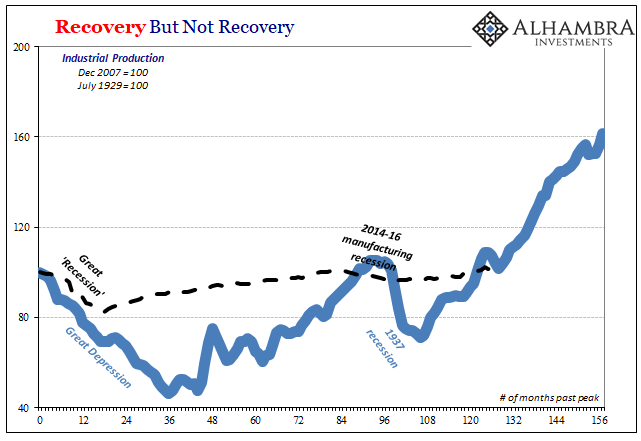

In other statistics it’s already been worse. One of the few, really the only, data points that goes back far enough to give us a consistent series through both time periods is Industrial Production. The 2010’s have already been weaker than the 1930’s.

Despite the boost from WWII, US industry never did get back on the same track as it had created during the twenties. We can, despite the media blackout in favor of the unemployment rate, relate.

In short, people like Paulson have spoken too soon; as if they have been in a rush to move on from the conversation. They’ve been making these claims throughout the last decade as if it matters. The only thing that does is where the economy goes after it confronts a massive dislocation. That much was proved by the 1930’s.

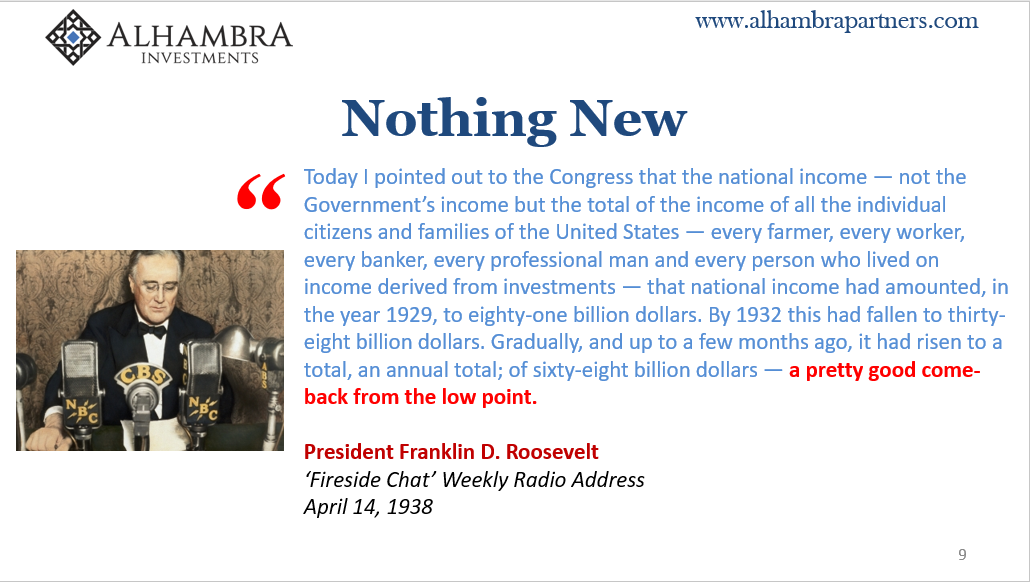

As I pointed out in Toronto last month, the message has actually been the same both times. In the thirties, it was FDR who kept trying to claim that the economy was good enough. It hadn’t recovered and certainly by 1938 it appeared as if it never would. But good enough wasn’t anywhere close to good or enough, as the generation who gave their lives in the forties would tragically find out.

In the 2010’s, FDR’s good enough has become jobs saved, or, as Paulson echoes from others, at least it wasn’t the thirties. Yet, it has been the thirties. The history of the crisis didn’t stop being written in March 2009.

This is the economy into which the FOMC is now “raising rates.” They call this “strong”; it is a preposterous proposition. An economy that can’t even match the decade of the Great Depression warrants the removal of accommodation?

This is the big issue at the heart of the matter. The Fed (and other central banks around the world who are equally responsible for the global economy being plunged into this position) believes it has been accommodative – but only in the jobs saved sense. They are, right at this moment, repackaging good enough for another angry generation.

It’s not. Not even close. Prolonged stagnation leads nowhere good. We’ve only experienced a taste to this point, global social order coming apart at the seams. Like the late 30’s, it’s impossible to know where the breaking point is.

Credit Paulson, Greenspan, Bernanke, and all the rest. They’ve managed a feat universally believed impossible. Now that’s hawkish. Nineteen forties hawkish.

Stay In Touch