The one thing the globally synchronized growth narrative had going for it was sentiment. It often had that in surplus. But therein lies a major drawback; are people happy because things are getting better, or do they believe things are getting better because “everyone” says so? There’s a difference and it’s a big one.

And it may not matter much any longer. Over the past few months, sentiment has been shifting. It isn’t as quite as universally negative as it was positive before, but, as the brave IMF spins it, the clouds are at least gathering on the horizon where nothing other than sunshine and rainbows were expected to gather.

This worrisome economic view has even penetrated far inside investor sentiment:

The poll showed that a net 38 percent of respondents expected the global economy to slow, the worst outlook on global growth since November 2008. A net 35 percent of participants identified trade war as the biggest risk.

Investors were also gloomy on corporate earnings, with a fifth of respondents expecting global profits to deteriorate in the coming year, BAML said, noting that in January a net 39 percent of investors had predicted an improvement. [emphasis added]

Wherever you see references to “trade war” as an offered explanation it is merely the stand-in for what’s really going on. Eurodollar squeeze as opposed to tariffs, the former cutting off global trade universally where the latter can only ever apply narrowly.

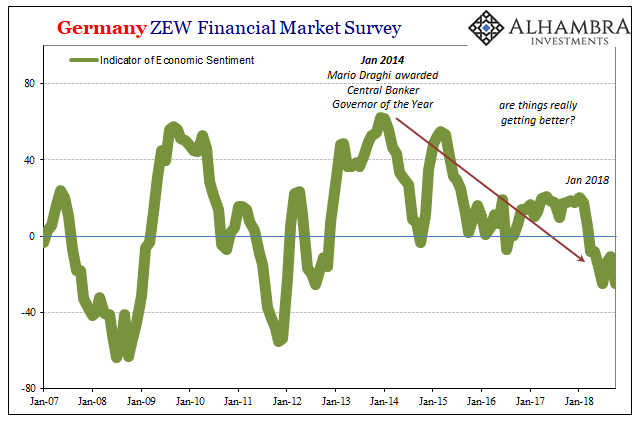

These worldwide factors are exhibited by those economies most exposed at the margins. China’s is one that tells us a quite a bit about where things are headed, as is Germany’s. Inside the engine of Europe, sentiment is captured again by the wrong direction.

Falling precipitously after January (dollar, not trade war), in a manner consistent with a global slowdown if not recession, the Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung’s Index of Economic Sentiment stabilized re-energizing some limited optimism. In July 2018, the index registered -24.7, the lowest level since Europe’s re-recession in 2012. Last month, it had improved to -10.6 sparking talk of “transitory” negative factors once again.

For October, however, the latest results released today, the index plunged back to -24.7 and matching July for the lowest in years. At this point in the upturn/downturn cycle, it’s not so much the degree of negative as it is time in the negative.

That’s the problem with sentiment as the key indicator for the optimistic case. It’s all about probabilities, especially in expectations regimes like orthodox monetary policy. If you as a central bank can get people to believe that things are going well, and keep them believing that long enough, they might just start acting that way. It’s the theory, anyway.

If, on the contrary, they no longer think positively the odds of anyone acting positively diminishes greatly. In other words, there wasn’t that much of a chance happy thoughts would lead to actual economic acceleration in 2017, but there is absolutely no chance for any in 2018 if sentiment has durably shifted. People will overlook short-term fluctuations, but if that change lasts long enough those same people will wonder what’s really been going on all this time.

Acting on negative expectations is asymmetric to acting on positive expectations; it’s far easier to cut back spending (businesses as well as consumers) given the limited income you have on the basis of growing worry and pessimism than it is to spend money you don’t because everyone on Twitter says the economy is booming.

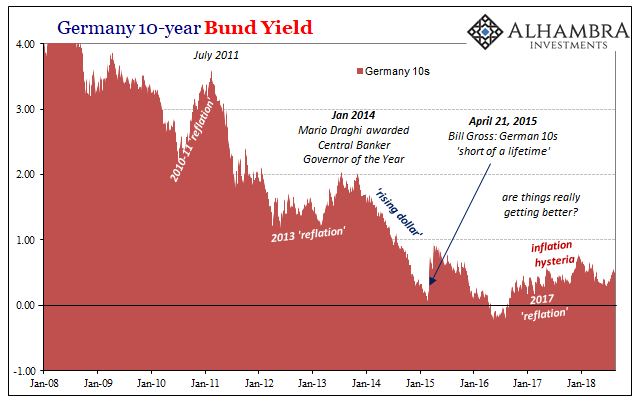

Furthermore, the more expectations around the rest of the world are reset very differently than how they were supposed to (inflation hysteria had it that people by the end of 2018 would be absolutely afraid that central banks were falling behind on economic overheating) the more the US “boom” falls suspect. Decoupling could be something if the rest of the global economy was at least moving forward, but if everyone else around the world is facing up to the prospects of merely the next downturn in the eleven-year (and counting) string then decoupling is exposed as little more than hopeful fraud.

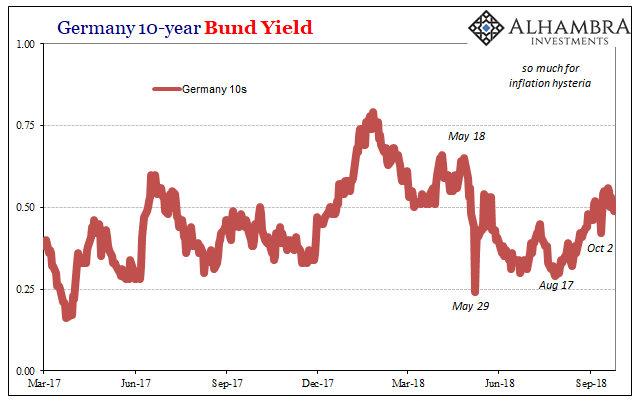

All these things are tied to what’s happened this year; not the mainstream spin on what might have happened this year, but the rather raw disturbances in key markets including Germany’s government debt market. May 29 already stands out, and it may be that over the balance of the rest of the year October 3 proves equally concerning.

In that way, market risks are more and more being seen and appreciated by economic sentiment – once more convergence down to markets which never truly left the pessimism camp. Some people are surprised by this, and there are many more who will be ahead. The last one is almost certain to be Jay Powell, who like his predecessor’s predecessor will in all likelihood be talking about acceleration risks as everything else comes down around him. He may not say subprime is contained but he’s already proving himself “worthy” of this new tradition.

Stay In Touch