If you think President Trump is upset with Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell, you should see what’s going on in India. Central bankers had been every government’s close friend for years; a decade even. The relationships were beyond chummy, particularly as many governments celebrated their central bank heroes for heroically heroic actions saving the world from something like a repeat of 1929.

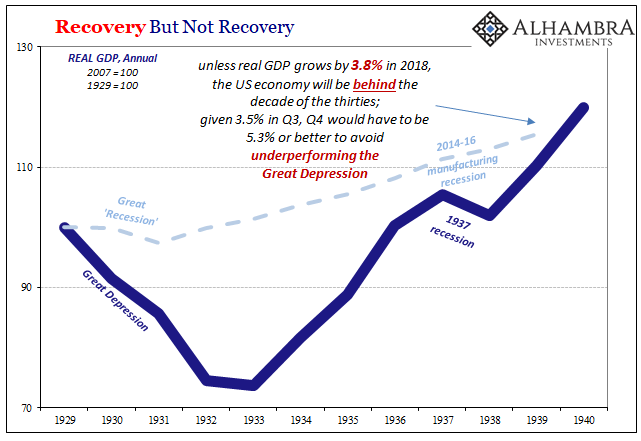

While conventional perceptions were shaped by things like QE and low rates, reality, of course, has been much different. Former Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson recently said people like Ben Bernanke saved us all from that other disastrous fate. Except the US economy is about to complete an entire decade where it has underperformed the Great Depression.

It’s the one headline you won’t see anywhere, especially not on a perfect Payroll Friday.

What that has meant for more than the US economy is often massive distance between broad categorized perception and experience. Central bankers say one thing and most of the time people believe them even if it doesn’t seem consistence with their own experience; even former President Obama is desperate to claim credit for this economic boom current President Trump is constantly talking about.

And yet, Trump is acting up about Jay Powell. It doesn’t follow, unless you realize the danger of a boom that never boomed.

It’s that way in India, too, only things have already descended to the extreme. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), that country’s central bank, has been operating a relatively constant monetary policy. Up until recently, however, that caused no disturbance nor disagreement. In other words, something has really changed.

India’s Finance Ministry has threatened just this week to invoke banking law if RBI doesn’t give in to demands from the Modi government. Unlike Western central banks, India’s is independent only by tradition. In statute, the RBI operates at the pleasure of the government. Section 7 of the central bank act hands authorities broad powers should central bankers act outside of established policy agreements.

These had been mostly informal up until the last two months. Again, the central bank was largely left alone because neither the Modi government nor Manmohan Singh’s regime before saw anything wrong with it. Any disagreements were minor and kept inhouse.

Not so any longer. There were media reports RBI Governor Urjit Patel had offered to resign earlier this week.

Modi’s complaints about “his” central bank run both to the familiar as well as the far more devastating. The Prime Minister has, like US President Trump, taken to criticizing “high” interest rates – even though RBI has raised its benchmark policy rate only twice in recent months and refrained from doing so at its most recent meeting. This comes after the central bank had been reducing them for two and a half years.

RBI’s rate which had been 8% was trimmed to 6% by the end of 2017. On October 5, the central bank abstained on a third rate hike which would have pushed it back up to 6.75%. It remains at 6.5% instead, hardly a serious measure for disruption and political turmoil.

This is scapegoating, pure and simple. Rate hikes are not what has changed the landscape in India. This is (thanks T. Tatteo):

The government wants the RBI to provide more liquidity to the shadow banking sector, which has been hurt by the defaults of major financing company, Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services (IL&FS). Those defaults triggered sell-off in bonds and stocks of non-banking financial companies. The government has been asking the RBI for a dedicated liquidity window for these lenders similar to one allowed during the 2008-2009 global financial crisis.

Modi wants the RBI to repeat its 2008 measures. It sounds sort of serious, right? Enough to trigger a government/central bank crisis.

These shadow troubles aren’t starting from rupee markets, a key distinction (like in 2008). I wrote on October 2, the day before the WTI curve shipped off toward contango:

For one, IL&FS is being characterized as a shadow bank and that’s the right way to think about them. As is the company’s very heavy dependence upon, you guessed it, Eurobond financing. Things started to go south even before India’s currency plunged along with all the rest. The rupee’s descent is merely the wrong side of “dollar” tightening.

The mechanics of oil are related to the eurodollar conditions for India and beyond. If India has gotten itself into a world of hurt, where is oil demand going to come from? That country was one of the last remaining places on earth, EM or not, where fast growth wasn’t just fairy tale talk. India has been, hands down, the best performing of the EM group.

Textbook deflationary disruption.

In other words, if the world economy loses India, too, placing that place alongside China in the eurodollar destructive column, WTI contango makes perfect sense having nothing to do with a supply glut. Eurodollar consistency in each market, foreign and domestic.

Modi’s sudden change of heart about Patel really has nothing to do with interest rate hikes. Makes you wonder about Trump’s similar reassessment of Powell.

Stay In Touch