Capital ratios are meant to help define a “good bank” for the public. The thought being a bank widely recognized and accepted as a good one will be far less susceptible to a run. But it’s the run regardless of capital ratios that destroys good banks as well as bad. The issue is, by and large, liquidity.

Officials have erred in one part because of how they view the banking system. To them, it’s still 1930 and depositors are the biggest bank concern. Bank regulation remains devoted to convincing the public the system is sound.

Both Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns were “well capitalized” by all regulatory definitions. Neither is with us any longer because depositors just don’t matter as much. Capital ratios were at best unhelpful, at worst in 2008 a wedge of mistrust. If Bear was really capitalized, and it was, all that “toxic waste” must be hidden everywhere.

In the aftermath of crisis, regulators have focused in on liquidity. They’ve done so in the same fashion and from the same prospective that led them to capital ratios. A couple of new measures have been developed which are supposed to answer for past holes in the supervisory burden.

Primary among them is something called the Liquidity Coverage Ratio, or LCR, drawn from Basel 3. This is the centerpiece of Janet Yellen’s confident declaration that another 2008 isn’t likely “in our lifetimes.” The banking system is so much better for how much authorities have learned from the last big one; which only begs the question, how could there have been the last big one?

This focus on liquidity is gleaned from that one simple truth. It isn’t losses that kill firms, good or bad ones, it is illiquidity. Lehman ultimately failed because like AIG it couldn’t meet collateral calls from its triparty custodian. You might think that would require some thought about the custodian’s role and how it operates rather than what happened specifically at Lehman.

The LCR was designed to fix this liquidity “flaw.” Banks are required to now hold High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) equal to 30 days of cash flow requirements. Meaning, if you today anticipate that you will have to fork over $100 for all business reasons you will therefore have to have today at least $100 in HQLA.

The Basel rules are specific about a “stress scenario” and what it might mean. If wholesale funding sources dry up for specific firms, should they be in compliance they will still survive 30 days which is figured to be more than enough for that stress scenario to be handily solved.

I know what you are already thinking, 30 days? As per usual, the Basel designers are already attacking the last problem from the position that central banks performed admirably when in reality it got as bad as it did because of their inadequacies (Eurodollar University Part 2); systemic deficiencies as opposed to idiosyncrasies.

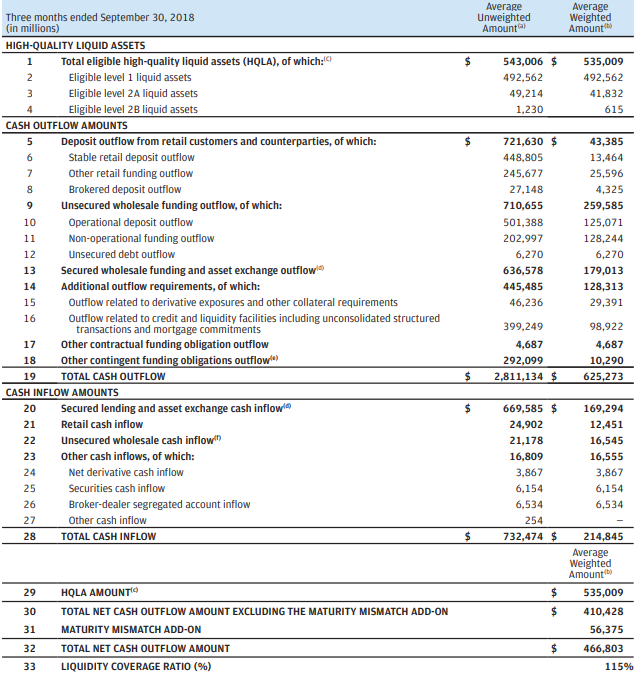

That’s not even the most suspect part, though. To come up with the LCR, a bank goes through a whole series of calculations. JP Morgan, for instance, shown above in its latest quarterly filing, has a current LCR of 115%. That is, the bank claims, in a “stress scenario” it holds more HQLA than it should need to cover all anticipated cash outflows.

What are those outflows?

These aren’t real, merely regulatorily-defined numbers that like capital ratios spit out a rigid weighted average. For example, the LCR rules say that whatever your “stable” bank deposit balances (and “stable” has a specific definition) you only have to include 3% toward Total Cash Outflow. That’s what the Basel designers believe is the worst case for depositors who are insured.

For other types of deposits, at least 10% (in JPM’s case, it is 10.3%) is contributed to the average weighted amount.

It only gets more complicated from there. For secured wholesale funding, repo, the bank can claim 0% cash outflow even if the transaction(s) is secured by HQLA but rehypothecated collateral so long as the maturity is beyond 30 days. For derivative transactions, the amount included as potential cash outflow is entirely dependent on the collateral.

There is, I can assure you, heavy reliance on collateral without really recognizing what that means.

This isn’t the biggest problem, in my view. What’s really eye opening is the HQLA. These are supposed to be assets that can be reasonably turned into cash at near full value at a moment’s notice (for a full 30-day period). Obviously, you expect UST’s to be included at the top of the list and they are.

What else qualifies? A wide variety of things.

Citigroup, as another example, in its last regulatory filing (10-Q) calculates its LCR in Q3 2018 as 120%. It’s been pretty stable around that level since the bank was required to report its LCR in 2017. Citi tallies Total Net Outflows (weighted) of $350.8 billion, against which it held on average $420.8 billion HQLA.

The majority of this activity is secured by high-quality liquid securities such as U.S. Treasury securities, U.S. agency securities and foreign government debt securities.

The filing indicates that $84.5 billion of the net whole is that foreign government debt, specifically:

Foreign government debt includes securities issued or guaranteed by foreign sovereigns, agencies and multilateral development banks. Foreign government debt securities are held largely to support local liquidity requirements and Citi’s local franchises and principally include government bonds from Hong Kong, Singapore, Korea, Taiwan, India, Mexico and Brazil.

What, no Greek sovereigns or Argentine Eurobonds? That $84.5 billion represents one-fifth of Citi’s HQLA stock.

Another bank providing detail is Bank of America Merrill Lynch. According to its last 10-Q for Q3 2018, the firm’s LCR was also 120% (as many of them are). Weighted HQLA (these are adjusted just like cash flow estimates) amounted to $440 billion drawn from Global Liquidity Sources totaling $537 billion.

Of that $537 billion, $130 billion is cash (unencumbered), $64 billion is UST’s (not pledged anywhere else, including repo), and $9 billion non-US government securities. The remainder, the vast majority, is $334 billion US agency and MBS (presumably marked down into a lower weighted category).

Etc., etc.

The LCR is designed like capital ratios to assure the public that these banks are sound because they will see the ratio and not what goes in it. The inclusion of the LCR (and next something called the Net Stable Funding Ratio, or NSFR) is meant to broaden the confidence to include liquidity as well as solvency factors. It does nothing to address deeper concerns, such as those which were actually involved in 2008.

What I mean by that is the Panic of 2008 wasn’t a depositor run; not even close. It was exclusively an interbank breakdown and one spread globally. Capital ratios didn’t help alleviate interbank concerns because they were irrelevant to them. The LCR similarly assures nobody in the same places. It is meant for public consumption not professional usage.

The banks operating in those markets know the games the ratios play, and how banks game those ratios. What do you think will happen when the first bank in the next crisis falls below 100% LCR? It will be allowed under the statutory rules, supervisors are given the authority to declare a “stress scenario.” Under one, any bank is permitted to begin selling HQLA because that’s what is supposed to happen.

But the first one who does will immediately be painted with stigma. Worse than that, the funding markets could interpret the use of HQLA as confirmation of a systemic breakdown. In many ways, oversimplifying, that’s what really happened in 2008. This ratio could make that negative determination easier.

The LCR only works if, like capital ratios, it is never used. Once a liquidity crunch becomes established, the LCR may become procyclical just like capital ratios were; the more banks dip into their stock of HQLA, the more likely, in my view, the marketplace will interpret that as a serious liquidity breakdown in the system. Liquidity is never pictured as an individual case. The problem, more or less, is not that these banks are covered for the things they do rather it is that they still do all these things.

At that point, does it matter if these institutions have 30 days of possible cash (or less, if something like MBS becomes increasingly hard to price)? One month may not be boundary it might seem.

But that isn’t really the purpose. The LCR, like capital ratios, is only meant for you not the repo desk at XYZ bank on the other side of rehypothecated Deutsche Bank collateral. The fault lines and potential for fragmentation remain because everyone still believes 2008 was about subprime mortgages instead of realizing it was a systemic breakdown across several dimensions – including geography.

And, in the end, it doesn’t matter if Janet Yellen is right. We don’t actually need another 2008 for some really bad scenarios. We have lived through two additional crises and are staring into the face of a third. The LCR is therefore something worse, a distraction from fixing the real problem.

Ultimately, I think that was the whole point. They had to do something. They gave us this unwieldly, massaged LCR so that authorities could point to progress. It won’t happen again, they assure us. Except, we aren’t really the ones who need to be assured.

Good bank or bad bank are terms that don’t really apply, they sure didn’t ten years ago. That’s the bait and switch, regulators who are trying to substitute more information suggesting each bank individually is sound, LCR now in addition to capital ratios, rather than any information and dissection as to whether the whole thing is. The theory prevails that the whole is the sum of its parts, and if the parts are good so is the whole.

Nope. The parts are at risk at all because the whole is still rotten. LCR or not, a breakdown will find a way and in places regulators still can’t conceive (because they haven’t looked). Again, the problem isn’t really bank panics.

Why are UST’s and German bunds (among others) still bid, meaning perceived liquidity risks still high? What was that collateral thing May 29? Ironically, the LCR might have a lot to do with it. It proves, yet again, authorities really don’t know what they are doing. They still don’t get it.

Stay In Touch