It’s always a fine line for authorities. There are times when avoiding intervention is more effective than intervention. That’s particularly true when the efficacy of whatever proposed policy is in doubt. If you don’t know for sure that it will work, maybe don’t do it. There are often grave risks associated with plunging forward recklessly.

In other words, officials can and do just make things worse. By pushing the envelope rather than calm markets or the economy they can further enflame them. Crises are never so binary – until they are over. Heading into one, there is so much ambiguity that can either work for you or against you.

Government desperation is one of those where it makes things worse. People may doubt there is a downside or how deep it might be, but if authorities are obviously unsettled that can’t be a good sign. From the official perspective, perhaps there just aren’t any alternatives.

China last night:

“There is desperation among regulators, and sometimes muddled polices are difficult to avoid under this kind of pressure,” said Jiang Liangqing, a Beijing-based fund manager at Ruisen Capital Management. “Investors are voting with their feet.”

In the last week, things have gone from bad to worse but all in the future tense. Right now, there isn’t any sign China’s economy is on the verge of collapse or even contraction. But the number of negative factors which could push it that far are piling up; mostly in the monetary therefore financial system.

The latest “desperation among regulators” this time comes the country’s Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission. Guo Shuqing, the chairman of the government panel, reportedly said yesterday that one-third of new loans created by the banking sector must go to non-state firms. Only one-quarter has.

On the surface, it sounds like very little, the usual Communist infatuation with top-down economic targets. But at this moment, the implication taken together with everything else suggests an almost bailout. Monetary tightness combined with possible further economic weakness could push China’s corporate sector into the abyss and it appears Chinese officials at the top are really worried about it.

Remember, most Chinese debt, dollar debt, too, was underwritten under very different conditions. It was universally believed that one of two things would ever happen: China’s economy would get back to its precrisis growth level, or, if it didn’t, the state would make sure it did by doing everything in its power to make it so.

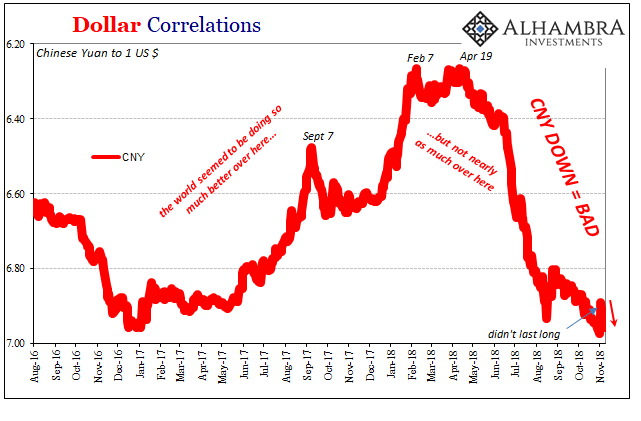

If you as a bank lender (China or eurodollar) suddenly realize the Chinese economy isn’t recovering like you thought and further that maybe it isn’t within the government’s reach to change the baseline, risk explodes. So much debt created the last decade, how much of it might really be at risk of default, or at least very difficult rolling over?

The economic stats all keep pointing in this direction. China’s economy isn’t right now collapsing but that isn’t the problem. Again, what the numbers suggest is we’ve seen the best there is and it isn’t (ever) going to get any better. And it isn’t near enough growth.

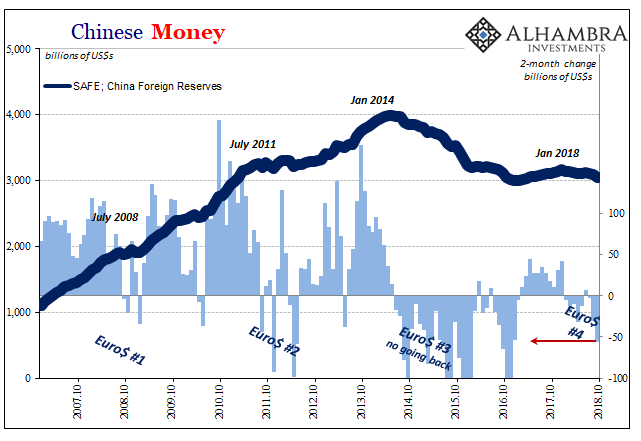

There just isn’t sufficient economic momentum anywhere in the world to overcome eurodollar tightening. In fact, the two go hand in hand; lack of momentum leads to monetary caution, spurning further growth creating more monetary tightening. The result is growing desperation in China, as elsewhere, about where things might be going just on the other side of the horizon.

These warning signs accumulate and escalate.

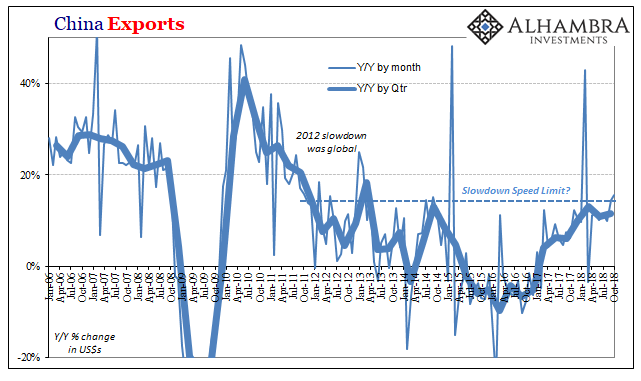

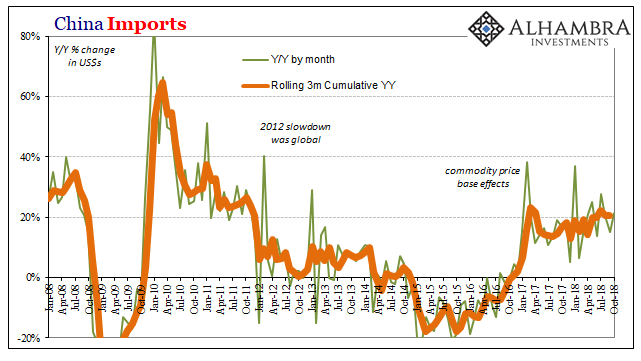

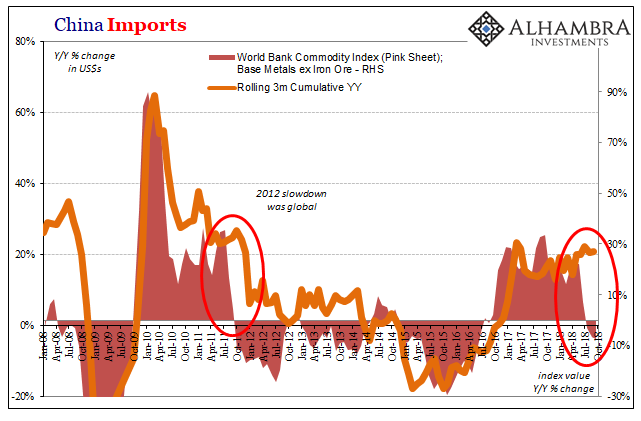

The latest statistics for trade and prices are all consistent with either the low ceiling or the impending rolling over. Chinese exports rose 15.6% year-over-year in October 2018, with imports up more than 21%. As usual, these sound terrific outside of any context. Inside, they suggest what commodity prices are starting to see – if this is the best it can be for China, it’s not nearly enough for either China or the world.

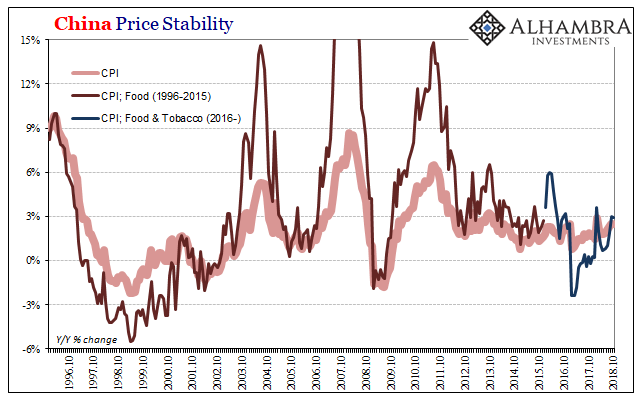

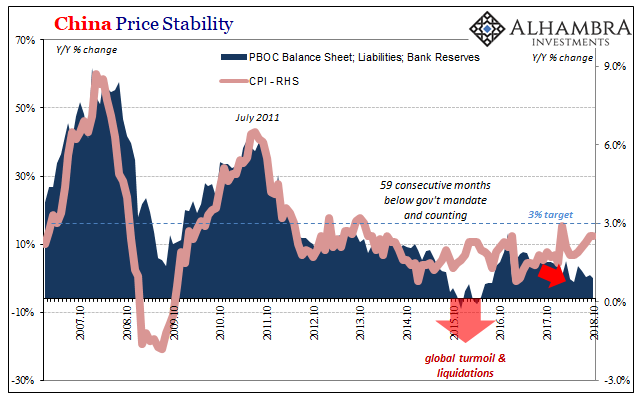

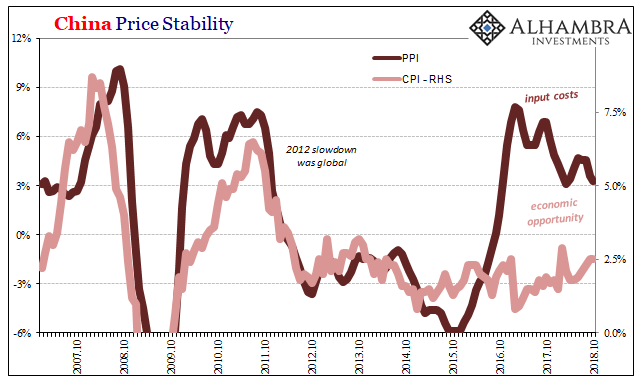

Internally, outside of bottlenecks in food, inflation remains subdued because monetary growth continues to be constrained. Even input and producer prices are coming back down because the (mini)cycle is turning. Reflation #3 was given a fair shot especially in commodity markets, and it just didn’t pan out. The screeching, emotional pleas for globally synchronized growth were never really based in honest analysis.

China’s CPI missed the government’s mandate for the 59th consecutive month. At 2.5% in October 2018, it was the same as September with food prices (including tobacco) still rising near 3%. The Producer Price Index was up just 3.3%, the second lowest gain since 2016.

The economy is stuck, which means markets and financial agents are going to realize that this if this is as good as it gets the “stimulus” panic in early 2016 didn’t actually create the economy everyone was looking for – and underwriting debt in anticipation of. Thus, not only is the economy trapped, what can authorities really do to get everyone out of it? Nothing. And now everyone knows it.

It’s not really difficult to appreciate why Chinese authorities are so openly freaking.

Stay In Touch