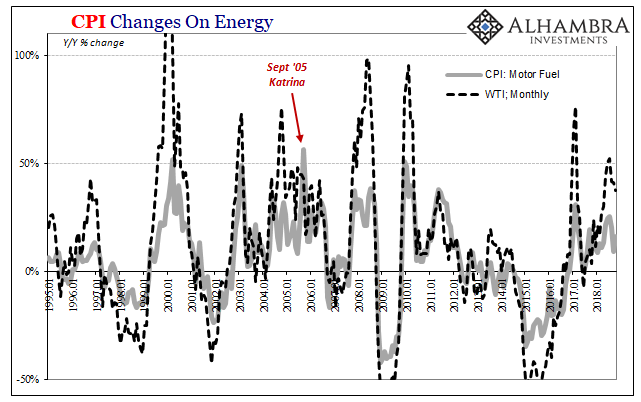

It was like a scene out of the seventies. Americans lined in their cars all over the Southeast hoping that their local filling station would have gasoline. There were documented reports of shortages as far away as the Dakotas. This wasn’t typical behavior, fortunately, so it couldn’t have been too much like the oil embargo era. Instead, in early September 2005, the blame fell on Mother Nature rather than OPEC.

Hurricane Katrina was a total disaster. What happened in and around New Orleans was a national tragedy. And the storm kept going. In its path people were rushed into emergency situations, which, if you’ve ever been in an area when a hurricane hits, means filling up every spare can and car with motor fuel.

The disruption in energy was of such a scale that for only the second time the President had ordered a drawdown from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (the first time was in advance of Desert Storm in 1991). On September 6, 2005, the Department of Energy issued a Notice of Sale for 30 million barrels, 15 million each of the sweet and sour variety.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Hurricane Katrina’s strain on gasoline production and supply caused a 56.5% year-over-year rise in the Motor Fuel component of the CPI for that month. Not all of that huge, painful increase was due to the storm as oil prices were rising throughout the period. Still, it was one month where the price of gasoline and the price of crude reversed positions.

If you look at the BLS’s consumer price basket for its average urban consumer, which is what the CPI is based upon, you won’t find crude oil in it anywhere. Why would you? The average American city dweller isn’t bidding electronically on NYMEX for pipeline access and storage capabilities. They only use the end product, and not all that much.

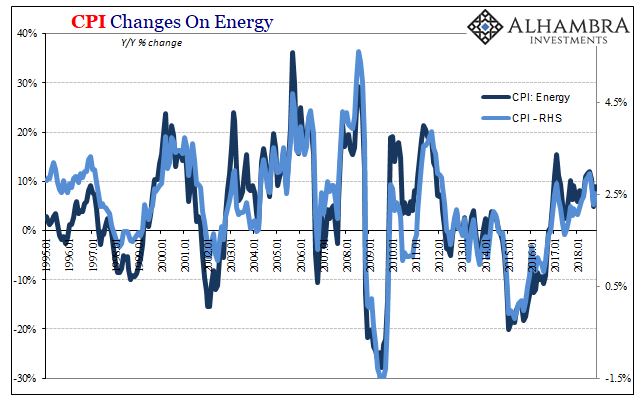

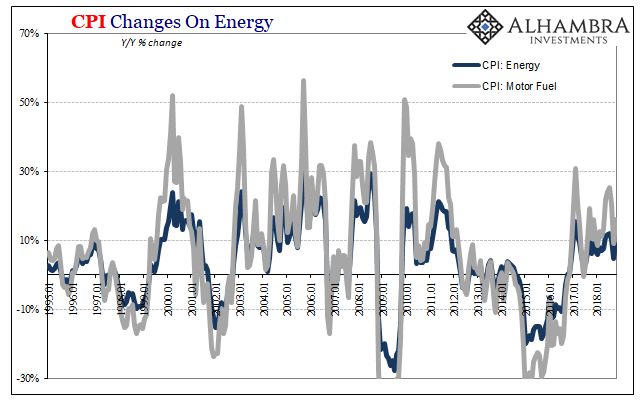

Within the CPI basket, the “relative importance” of motor fuels to that average citizen is only 4.437% (as of September 2018). Total energy, which includes filling up your car, is but 8% of the total index. So, despite the fact that crude prices aren’t included in the CPI and gasoline is only about 4% of the overall basket, still the headline index follows closely along from WTI’s trend anyway.

The reason is pretty simple – commodity price swings in especially crude are immense. A big jump in oil typically produces a big if tempered jump in gasoline; September 2005 being one of the rare exceptions. The more modest spike in gasoline produces a still more modest increase in overall energy. By the time it gets to the CPI total, it’s there but because it’s only a small part of the basket only the overall shape remains.

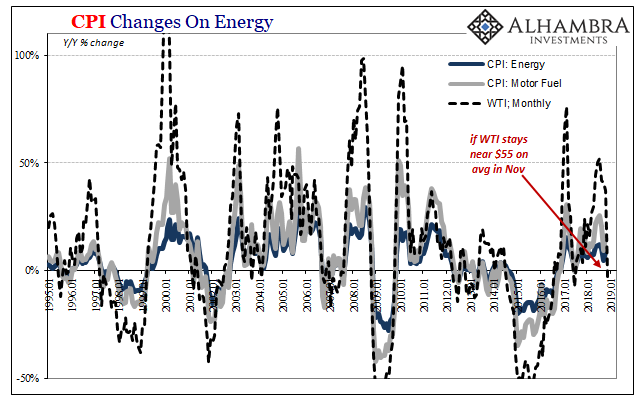

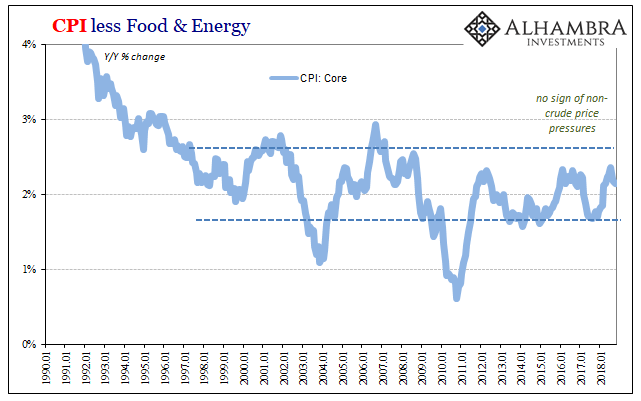

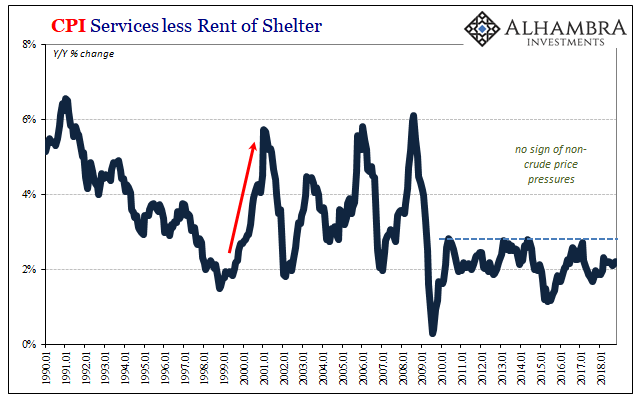

Why is Jay Powell so desperate for wage-driven consumer price gains? Because he absolutely needs the CPI, as PCE Deflator, to move away from just these oil price swings. While those were in his favor up until October 2018, they may no longer be moving forward starting in November.

The average monthly price of WTI was around $70 last month, though the front month contract receded sharply throughout. That compared to an average price of $51.58 in the hurricane aftermath of September 2017. The stout 37% year-over-year increase contributed to motor fuel prices (in the basket) rising 16.2% and then overall energy up 8.8% on an annual basis.

And still the headline CPI was just 2.5% in October, indicating for the PCE Deflator, the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation measure, a number too close to 2% even though the unemployment rate was 3.7% for the second straight time last month (and 4% or less for seven consecutive months).

Without something else, meaning actual economic growth, these inflation indices which have up to now provided statistical cover for FOMC officials will begin to turn against them all over again. The oil price crash, if it continues or even holds at prices where they are now, will look like this for a starting point in November:

The average for WTI in November 2017 was $56.54, which means a furious rally or the inflation indices begin to conspicuously soften. The WTI downturn, should it continue, won’t register in gasoline therefore overall energy straight away, but the headline will notice the direction.

What’s more important is what would be beyond the month of November. What happens to Powell’s big recovery narrative should the major consumer price indices fall back below not just the official target but recent months that were near to them? The world starts to think about nothing but the downside again, another instance where Economists prove they really have no idea what they are doing.

The unemployment rate so obviously divorced from the CPI means a lot, actually. It shouldn’t mean anything, but that’s not quite the world we live in (yet). Oil prices are fickle. Maybe they come back, though the contango says this isn’t likely. Jay Powell’s probably going to need a new spin on “data dependent.” Then again, he could just risk it by reusing “transitory.”

Either way, it could add up to the US statistics moving in the same direction as the rest of the world in 2018. The wrong one.

Stay In Touch