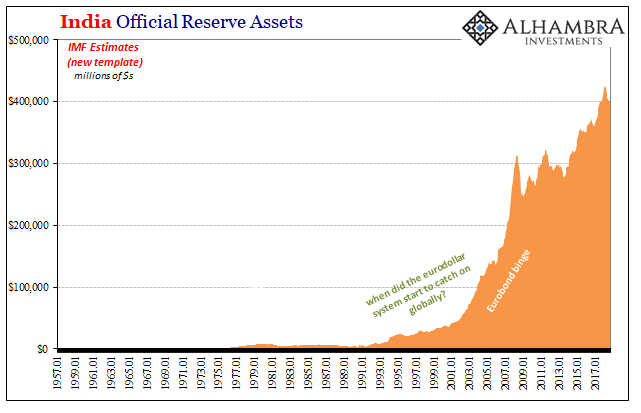

Banking regulation is never easy. Shifting regimes and tightening things up a bit during a rip-roaring global economy, however, makes it much less stressful. Among global banking systems the one in India has lagged. Much of the rest of the world had moved on to higher capital requirements in addition to (sappy) liquidity constraints long ago so as to keep something like 2008 from happening again.

It has only served to demonstrate just how little regulators figured out about that supposedly long ago crisis in any one place let alone across the world. To catch up with fighting the last problem, the Reserve Bank of India alongside state banking authorities have been pushing banks to hold more capital. Until this year, that is.

Last month, under intense pressure from the government, India’s central bank relented before imposing the last part of higher capital requirements. These were strengthened in 2017 with every expectation counting on continuing the process, but the world in 2018 is very different.

The final level for the Capital Conservation Buffer (CCB), as it is called there, will now be pushed back to March 2020 at the earliest. The Modi government has become increasingly apoplectic about what it sees as unnecessary “tightening.” They have gone so far as to threaten to impose monetary policy on a central bank, RBI, that isn’t legally independent.

The dispute has now claimed not just regulatory relief but now one top official. If anyone at RBI wishes to lash out at foreign “dollar” tightening again it won’t be Governor Urjit Patel. Dr. Patel in June pleaded with the rest of the world to heed his country’s plight, only to have his words fall on deaf ears (as always). Writing in the Financial Times, he urged policymakers to consider what was going on with the real global reserve currency system (incorrectly blaming the Federal Reserve for it).

Despite caving on the CCB as well as a couple of other measures, Patel resigned earlier today. What’s really at issue is not rupees:

Mr Modi has been accused of demanding that the RBI ease back on its crackdown out of fear it will hit economic growth during his drive for re-election, particularly as liquidity in non-bank lenders has dried up after a series of defaults at IL&FS, a high-profile finance and infrastructure group.

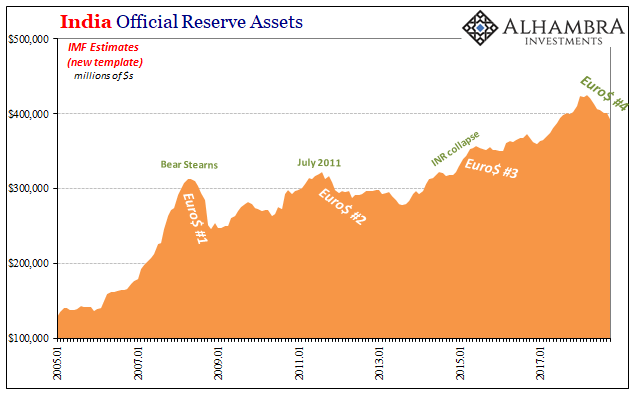

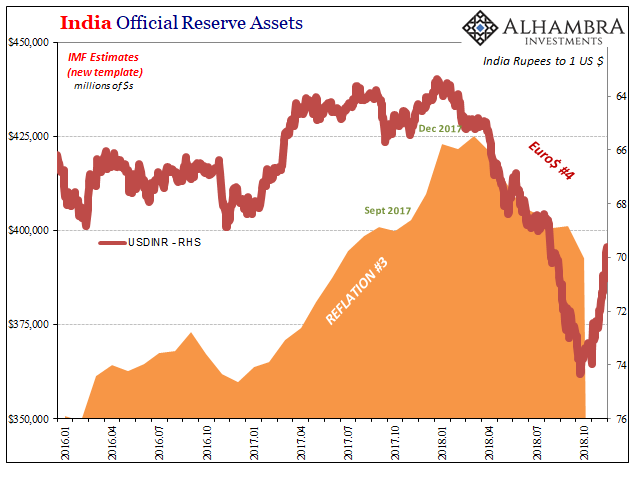

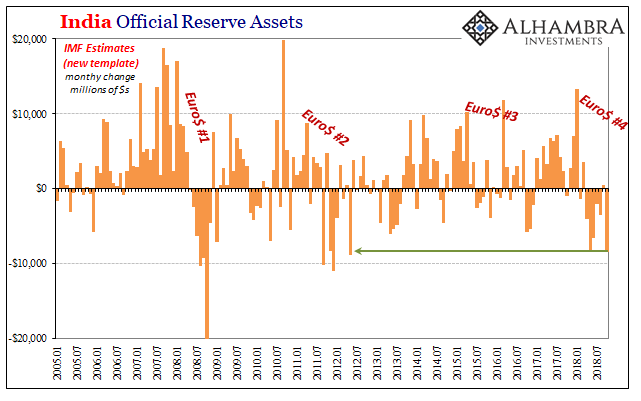

Increasingly, Eurobonds and eurodollars are off the table for India’s shadow conduits; IL&FS is only the largest. What has India done about it? For much of this year the RBI has dangerously dipped into the country’s reserves, a big change from how things were done during the last bout of global eurodollar distress (#3).

At each prior downswing interval (#1 and #2), RBI had opted for a more direct intervention approach. For the most part, it had worked as India’s rupee remained largely stable (though volatile) especially when compared to its peers. The economy followed suit.

It all changed 2014-16 for reasons that haven’t been fully documented and published. Perhaps the central bank fears what has become all-too-apparent elsewhere; that intervention equals being doomed to failure. It has become one of the major sticking points as things have spiraled further out of control.

Tensions between the RBI and Mr Modi have been mounting for months over the central bank’s hawkish monetary policy, use of its mounting reserves and the tough measures taken to clean up bad loans at India’s state-run banks.

The use of reserves in November, a month when INR pulled up from its steep dive, hasn’t yet been published. Given the context of Patel’s resignation as well as the continued political turmoil surrounding the central bank, we can reasonably guess that there might have been an escalation in usage. It would be on top of what already has been highly unusual levels of involvement and reserve mobilization so far.

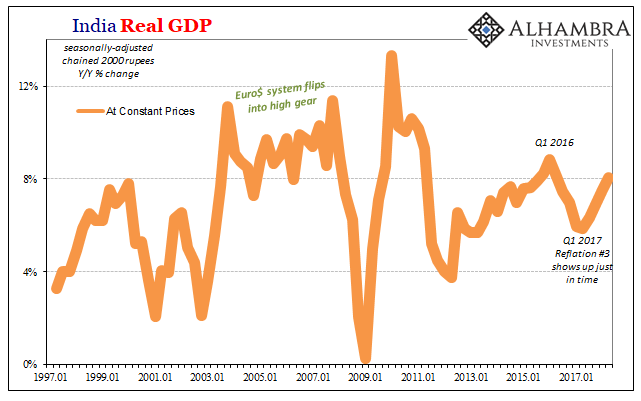

From the perspective of the government, the risks to the economy are clear enough. India’s economic acceleration and recovery from the Great “Recession” was largely intact up until Q1 2016. Unlike most the rest of the world, the Indian economy followed its own course of continuing improvement so long as the currency remained stable – with the government arguing the use of reserves key to maintaining the trend.

Fortunately for India, Reflation #3 came along when it did. For the balance of 2016, it appeared as if India might follow China and everywhere else toward the abyss. The upturn in especially the Eurobond market during late 2016 and into 2017 was a measure of salvation, though ultimately a false one.

IL&FS became hooked upon the global dollar bond market in lieu of global dollars via global eurodollar banks. It seems nobody was expecting this imperfect alternate method of funding would turn out equally if not more fickle than funding through the bank channel (globally synchronized growth, after all).

Regardless, having seen India’s recovery pushed dangerously off-track in 2016 there is little appetite for it to repeat the experience with now a fourth eurodollar event (encompassing, if not originating in, Eurobonds this time, too) expanding out over geographical as well as time horizons. Only, what does anyone do about it?

On the one side, we have local monetary and fiscal agents struggling against the consequences of a malfunction global reserve currency. On the other, we have Western central bankers who have no idea what that is. Thus, Patel’s desperate admonishment several months ago. It’s a standoff between those directly affected and the grossly incompetent who have no idea what anyone is talking about.

Impasse doesn’t even begin to describe it.

The only predictable result is a global economic standstill – as a start. I’ve written before why India’s experience in 2018 might matter a whole lot more nowadays, what it means for the rest of the global system that it might not have during the last one three, four years ago:

The mechanics of oil [and global economy] are related to the eurodollar conditions for India and beyond. If India has gotten itself into a world of hurt, where is oil [economic] demand going to come from? That country was one of the last remaining places on earth, EM or not, where fast growth wasn’t just fairy tale talk. India has been, hands down, the best performing of the EM group.

Neither Modi nor Patel wanted to find out what happens if India does follow China into perpetual slowdown. Unfortunately, it may not have mattered who won the political contest. Modi has come out on top in this battle, but when the eurodollar system is involved in this way history has shown there are only losers in the end.

It may just be that there are no good answers here, chaos the inevitable fate. Again.

Stay In Touch