If there is one thing Ben Bernanke got right, it was this. In 2009 during the worst of the worst monetary crisis in four generations, the Federal Reserve’s Chairman was asked in front of Congress if we all should be worried about zombies. Senator Bob Corker wasn’t talking about the literal undead, rather a scenario much like Japan where the financial system entered a period of sustained agony – leading to the same in the real economy, one lost decade becoming a second and then a third.

Bernanke retorted that there weren’t going to be zombies in the United States. The American people needn’t worry because the key to staving off economic apocalypse was pretty simple.

If there is one message that I’d like to leave you with, if we’re going to have a strong recovery, it has got to be on the back of a stabilization of the financial system.

Bernanke was already busily trying to do just that, steady the banking system. Unfortunately for all of us, while he could see what needed to be done, doing it was altogether a different matter. His tenure was a total failure for this one thing. Neither he nor any of his fellow central bankers had any idea how to put this theory into practice.

They really don’t know what they are doing.

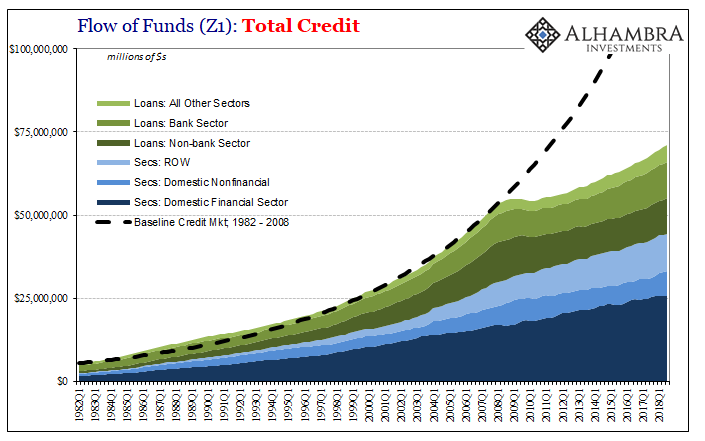

As I write almost every quarter at each update of the Federal Reserve’s Financial Accounts of the United States (Z1), there is a necessary debate still waiting over how much debt is the “right” amount. There are legitimate concerns about too much. What isn’t up for argument is the last ten years; Bernanke was, again, correct in that debt is a requirement in the modern financialized economy and to make it we all need confident, functioning banks.

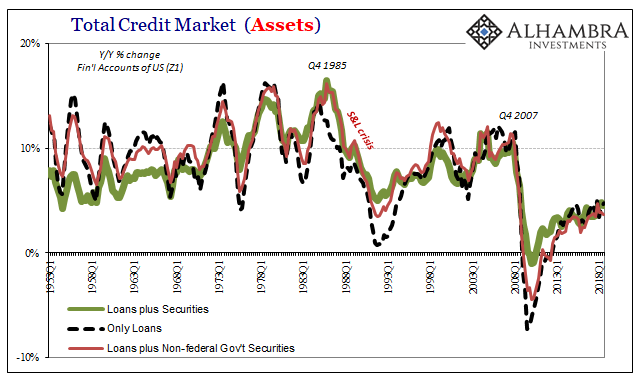

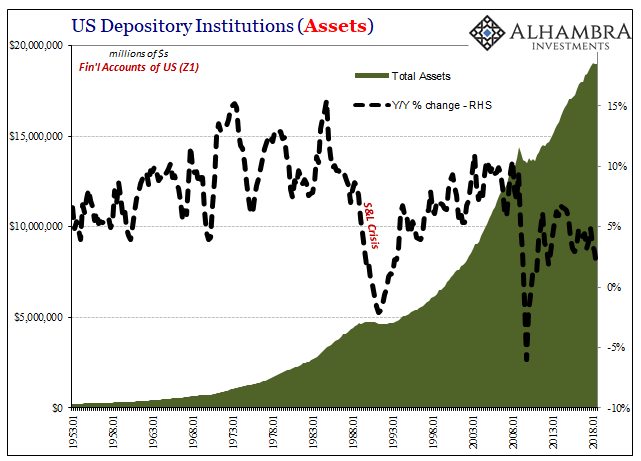

No matter what the Federal Reserve tried, credit growth remains conspicuously stalled. The latest Z1 update for Q3 2018 shows quite a bit to be concerned about in terms of financial participation. The overall credit market is slowing – again.

Excluding the mind-boggling debt of the federal government, total credit (both securities and loans) was just a little more in Q3 2018 ($53.6 trillion) than it was the quarter when Lehman failed ($47.9 trillion). Worse, total credit last quarter was barely more than it was in Q2, the second nearly flat quarter this year (Q1 was slightly worse still).

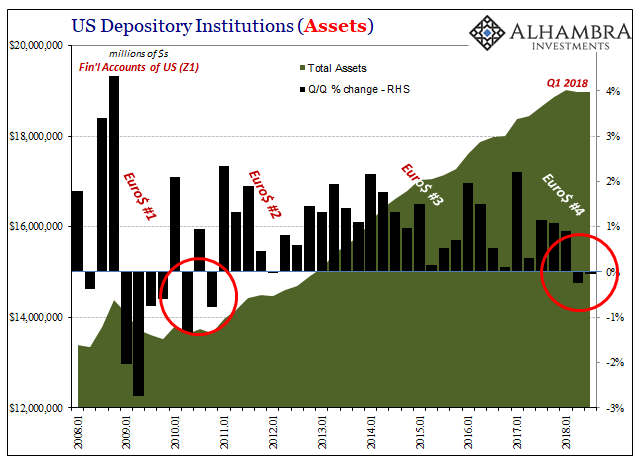

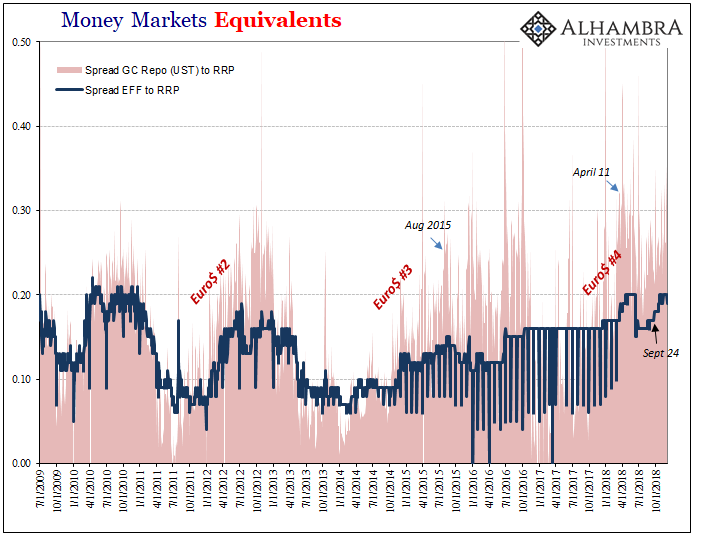

The reason is clear enough – banks. The banking sector continues to malfunction; but not in some random sequence of “unexpected” troubles. Nor does this correspond to regulatory changes, as some keep trying to claim. There is no 2a7 money market reform to blame like in 2016, nor the imposition of Basel’s LCR (joke) as in 2014.

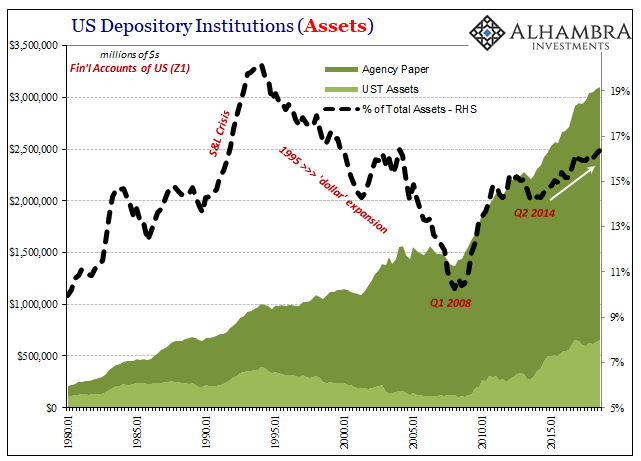

US Depository Institutions are still buying up the most liquid assets, of course. The phasing in of LCR requirements is long over but domestic banks and foreign subs located in the United States remain keen on UST’s and agency paper regardless. They are expressing a clear liquidity preference, keeping the predictions of the BOND ROUT!!!! to Economists not trading desks.

Since the last “rising dollar” period in the second half of 2014 Depository Institutions have increased their portfolio allocations to these most liquid assets by two percentage points, from 14.3% of all assets in Q2 2014 to 16.3% as of Q3 2018. It’s as if over the last four years the banking system, quite surpassing any LCR requirements, remains very concerned about global liquidity risks.

Those seem to have taken banks by storm in 2018. We know what this year has meant in markets, turmoil that isn’t actually overseas. The Z1 estimates show us just how astounding this latest disruption has been. For the last two quarters running, the banking system has shrunk.

This hasn’t happened since 2009 and the last remnants of the big panic. Domestic US banks haven’t been this unsettled since 2010 before QE2 (which only goes to show, yet again, how QE was a total fraud). Inside the domestic financial system, Euro$ #4 is already shaping up as a pretty big one, not that we didn’t really know it from real-time indications.

Total asset growth, not just bank credit, has ground to a halt. With banks allocating more to UST’s and agency securities, outside of the liquid class the financial system is at a standstill. In Q1 2018, Depository Institutions were collectively holding $15.98 trillion of all other types of assets besides UST’s and agency debt. As of Q3, they own $15.87 trillion.

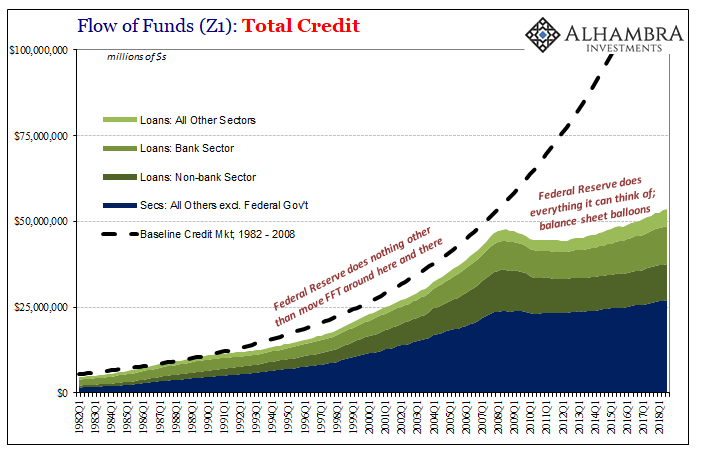

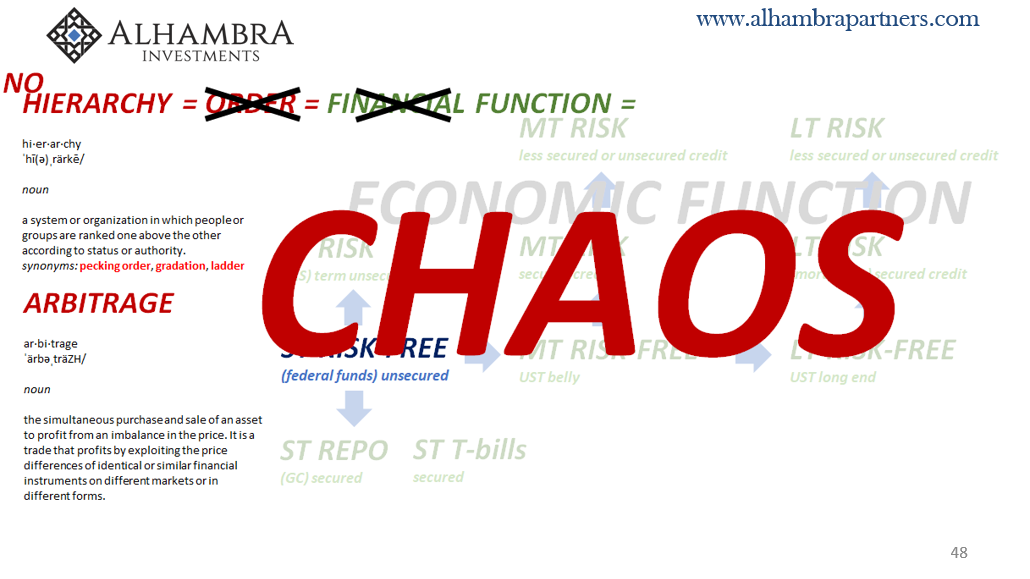

The deflections and excuses will be different this time: QT, higher interest rates, trade wars, T-bills, etc. The pattern, as the baseline, however, remains the very same. The financial market was never fixed no matter what program any central bank conducted over the last eleven years. Every time it looks like things might improve “something” interrupts the healing process and sets the whole system back so that it can never escape this malaise.

The economy is therefore trapped by the same instability.

Bernanke was right, the financial system needed to be reset and restored. To do that would’ve require first a monetary reset; the crisis was never about subprime mortgages as the former Fed Chairman was trying to claim back then. If it was, something like QE (a simple asset swap, not money printing) might’ve had a chance (even then it wouldn’t have been a sure thing).

When the fissure instead resides in the world’s reserve currency system it’s a much different proposition. The banking system is being reminded in 2018 big time. When talking about retreat and retrenching here, being compared to 2009 and 2010 is the last thing anyone wants. Banks are uneasy in a way they haven’t been since some pretty dark days.

Maybe this time someone will actually try to find out why instead of queuing up QE5. I wouldn’t count on it. Banks weren’t at risk of being zombies, it was central bankers who actually became mindless, repetitious sleepwalkers. The costs continue to mount and for much more than the global economy.

Constant monetary instability >>> financial instability >>> economic instability >>> social instability.

Stay In Touch