The English language headline for China’s National Bureau of Statistics’ press release on November 2018’s Big 3 was, National Economy Maintained Stable and Sound Momentum of Development in November. For those who, as noted yesterday, are wishing China’s economy bad news so as to lead to the supposed good news of a coordinated “stimulus” response this was itself a bad news/good news situation.

If the Communist State Council is to be flustered into action, the title of the release might suggest maybe not. Then again, there isn’t a month that goes by where the NBS writers don’t write pretty much the same thing. In a Communist country, any wording less than “sound momentum” is surely frowned upon especially when there is no momentum.

Underneath, the figures were all bad. Were they bad enough? I don’t believe anything short of full-fledged collapse will be, but this is attempting to game and analyze a political factor whose proportions are never going to be fully known.

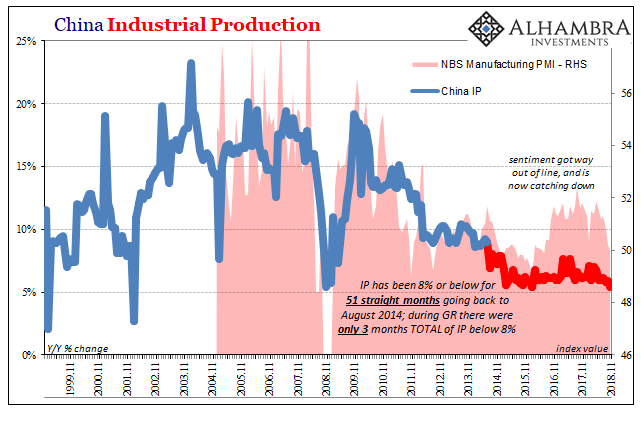

What we are left with is pure ugly. The last time Industrial Production grew at a 5.4% annual rate, as it did last month, it was February 2016 and the worst of times for modern, industrial China. It was also the same month the last “stimulus” was uncorked.

It doesn’t get any lower than the 2015-16 downturn so for Chinese industry to already be at that depth with “this one” just getting started, it all tells us that perhaps there is a lot of downside left to come and that officials are keenly aware of the possibility.

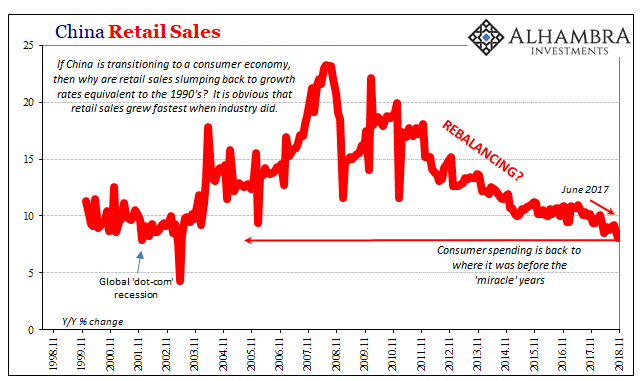

If this was somehow unexpected and unapproved, so to speak, they wouldn’t have waited for 5.4% to reappear. That goes double for consumer spending, or retail sales in this case. Chinese retail activity grew by just 8.1% in November. You have to go back fifteen years to find something less.

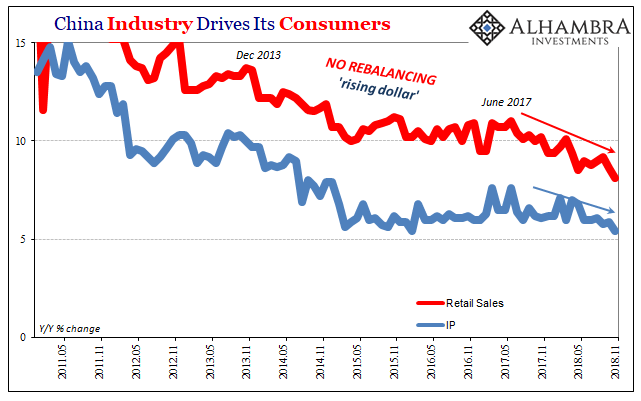

What should really stand out especially for the stimulus whisperers is when China’s latest economic inflection transpired. It wasn’t Trump and trade, it was in the middle of last year for both IP as well as RS.

Why mid-2017? That was when authorities began to realize the full extent of their predicament. They had done the “stimulus” stuff in a rush to begin 2016 and it didn’t get anywhere. There are often heavy costs to doing these kinds of things, so to pay out a lot and receive very little in return from it is a big counterpoint to thinking about doing it again.

China simply has, as we’ve been writing and speaking about for half a decade (and more, less specifically about China), no monetary room with which to get any kind of internal growth started. That point was driven home last year. The global economy despite all officials protestations everywhere has never once picked up toward recovery.

Therefore, the Chinese government is left between the rock (external malaise) and the hard place (no internal monetary space). Only a few months after June 2017, Communist officials convened at the 19th Party Congress and “elected” to move authoritarian. This, I don’t believe, is mere coincidence.

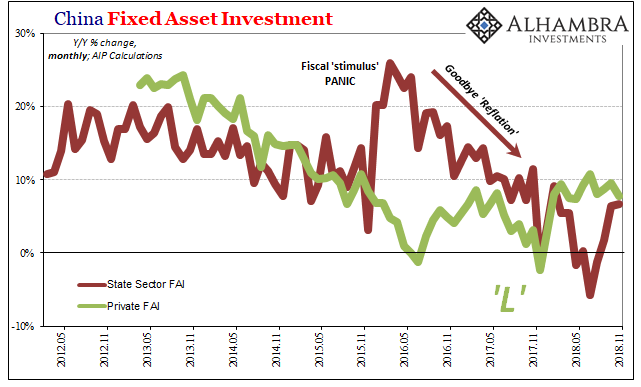

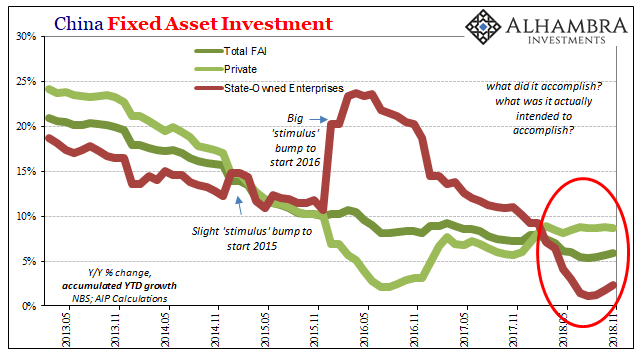

The only mild positive so far in 2018 is how Fixed Asset Investment (FAI) has stabilized albeit at extremely low levels. Private FAI, in particular, is growing at around a 9% rate (8.8% in November) which is better than late last year.

The flipside of that is how Private FAI seems to have hit a ceiling around 9%, nowhere near the 25% rate that for a few years kept China out of trouble. Even with officials at lower levels (almost certainly on orders from the central government) in the provinces no longer clamping down on the waste of State-owned FAI, it hasn’t stabilized China’s economy because it can’t.

On an accumulated basis, Public FAI rose 2.3% in November (meaning YTD) while on a monthly basis it was less than 7% (annual rate) for the second straight month. Like Private FAI, better than before but not really meaningfully so. It seems more like messaging than meaning.

To me, this adds up to the same thing – an attempt at managing the decline rather than intentions to turn it around as expectations for globally synchronized growth would have required. I wrote more than three years ago, a little over a week after the big shock of CNY in August 2015:

I think they made a conscious effort to try to avoid Japan’s disaster by actively engaging to manage a bubble decline regardless of how much growth had to be “sacrificed” to do so.

That the Chinese would attempt such a “hail mary” to me cemented the Japanese analogy – they had to try because not doing so, the Japanese path, was far, far worse than the dangers of managed decline getting out of hand. A small probability of success was far better than what surely awaited doing nothing.

This obviously matters given the three years in between for how important China is to global growth, but equally for what it says about the world’s economic situation in 2015 and 2018. What I wrote then still fits this many years later:

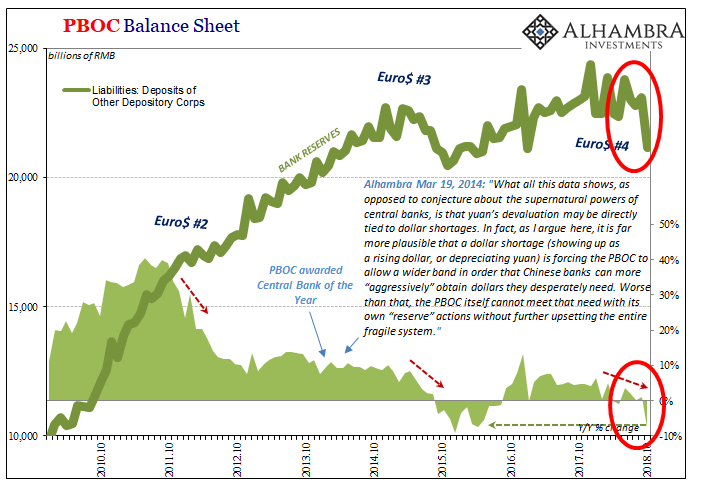

In Japan’s case, the believed restoration of a more favorable external balance did not arrive before the monetary expiration. I think that is where the PBOC was in 2013, namely that it took the 2012 global slowdown as the final say in the matter of “the other side”; there was only to be an ugly economic fate.

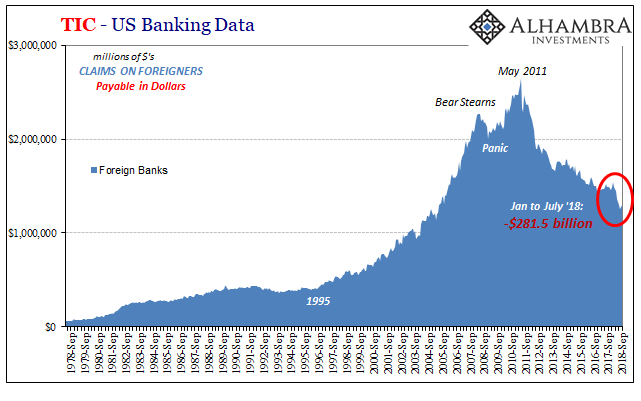

The Chinese began to realize what Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen refused to accept; after 2011 there was not going to be a global recovery because there could not be one. The 2011 eurodollar crisis, number two, had been the final say on the matter. When CNY started to fall, meaning the “rising dollar”, in 2014, that was it; the final final nail in the coffin.

China’s economy could get by in 2017 with a few magic tricks (HK) covered by Reflation #3 globally. But in the renewed eurodollar pressures of this #4, the monetary noose could only tighten that much more internal as well as external. CNY DOWN = BAD.

Maybe the Communists do panic next week surprised not at their own misfortune but by the levels of complacency and denial across the rest of the planet. Somehow, I doubt it. This is nothing more than the same worldwide “L”, for managed decline is still decline. It surely was that in China in November.

Stay In Touch