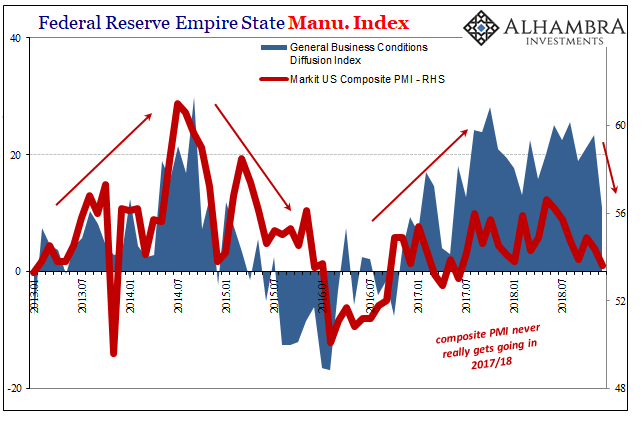

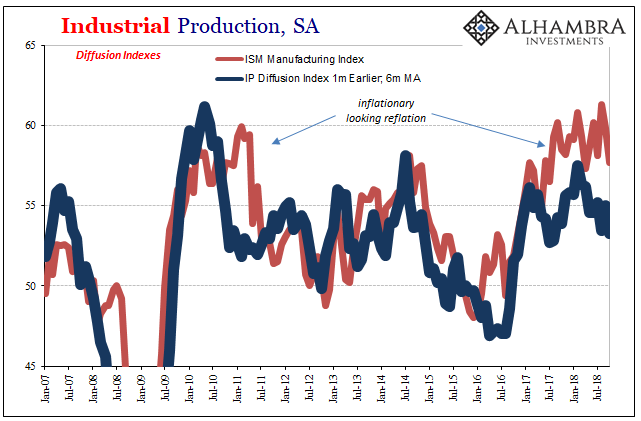

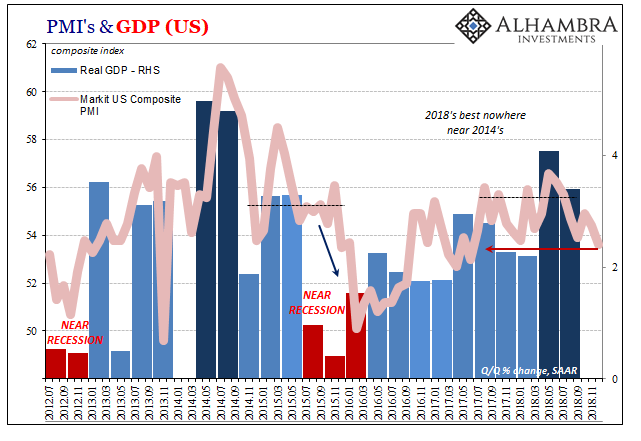

It is time to start paying attention to PMI’s again, some of them. There are those like the ISM’s Manufacturing Index which remains off in a world of its own. The version of the goods economy suggested by this one index is very different than almost every other. It skyrocketed in late summer last year way out of line (highest in more than a decade) with any other economic account. For that reason alone, it has been widely cited for this “booming” US economy.

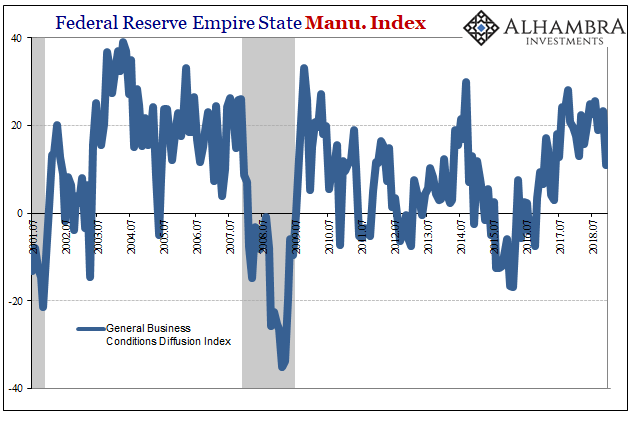

Other’s showed the same trajectory if not anywhere near that level of enthusiasm. But while the ISM remains at lofty levels, these alternates are starting to move back down again. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s General Business Diffusion Index, otherwise known as the Empire Fed, registered its lowest reading this month since before 2017’s busy tropical season for the central bank’s Second District.

Like the ISM, the Empire index suggested manufacturing was experiencing a revival that the rest of the economy wasn’t. But if those were of the best possible case in late 2017 and early 2018, the current condition and more so indicated direction at least for the Second District can no longer be classified that way.

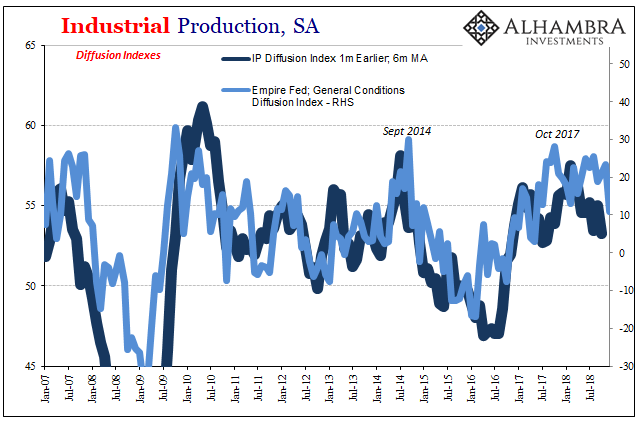

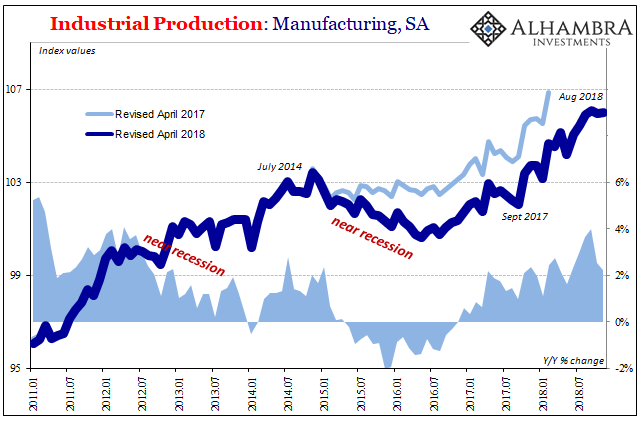

There is much more corroboration of this view than the ISM’s continued unearthly persistence. The Federal Reserve also maintains a national diffusion index (actually three, of differing time intervals) as part of its estimates for Industrial Production. Its measure of sentiment more closely resembles (on average) that of the Empire Fed’s.

That’s the bad news. The economy may or may not have been booming overall, but in the past few months the condition seems to have rolled back.

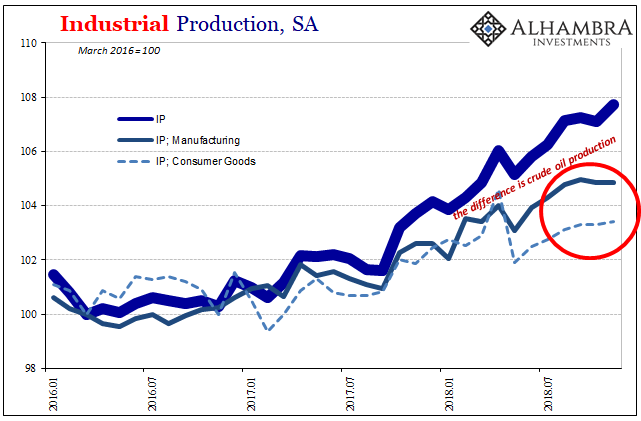

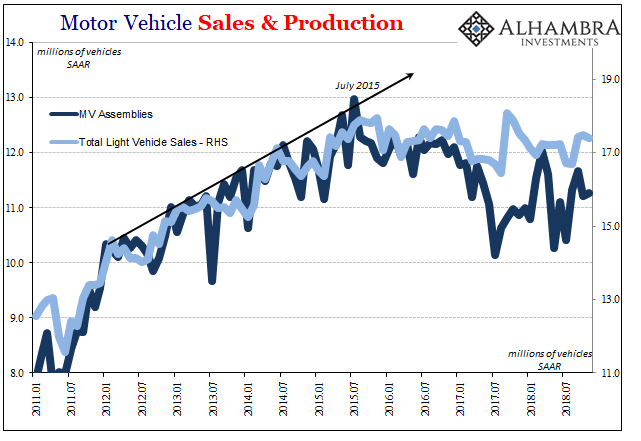

The IP figures themselves already propose that prospect, meaning consistency from sentiment to estimated activity. US industry has been pulled in different directions by the curious tug-of-war between crude oil and automobiles. The mining sector particularly oil production has been actually booming; the vehicle sector not so much.

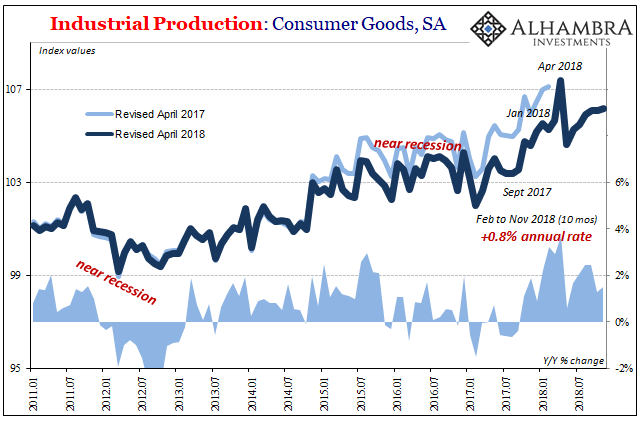

While the crude extraction process keeps on producing, the manufacturing sector, reiterating sentiment, has not. Manufacturing overall has been flat for four months in a row, while in the consumer goods segment this lack of forward growth has been apparent for all of 2018 outside of two months earlier this year.

The production of consumer goods in November 2018 wasn’t even 1% more than in January. This period coincides with the initiation of tax cuts but also aftermath of 2017’s noisy and unusually destructive hurricane season. There was an obvious boost (after September 2017) due to the latter as well as a clear absence for the former.

The two months March and April spiked on this year’s other mainstream topic, trade wars. Moving past all of them, we are left with little growth and now the prospects for diminished expectations coupled with financial volatility.

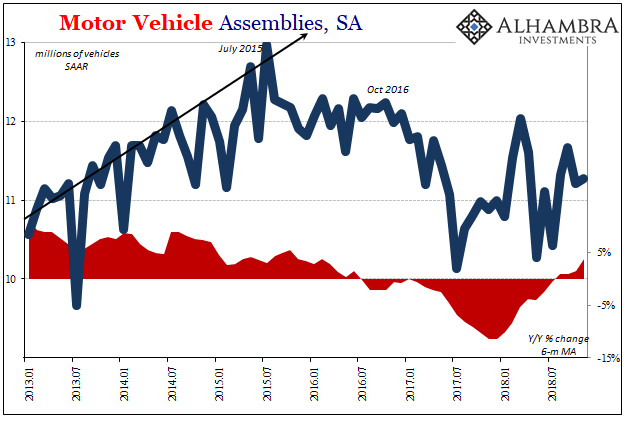

That begins in an auto sector that just cannot get going. The car business has been stuck in recession for three years running, moving closer to four years. It isn’t that autos are an especially heavy piece of the economy anymore; they aren’t. However, they are a key piece of consumer activity and therefore, like housing, it tells us something about the state of consumers – real sentiment leading to actual spending as opposed to public surveys that have seriously diverged.

Both autos and housing confound and refute the picture of the economy provided by the unemployment rate.

Putting it altogether, it seems that unlike prior reflations this last one (Reflation #3) was much more confusing than those that came before. There was the obvious contrast between economic perceptions given off by something like the ISM and actual activity that was noticeably subdued even when compared to prior similar periods (2017-18 was obviously less than 2014, yet that’s not how it had been described).

The introduction of so many artificial factors made the checking of assumptions all the more important, and at the same time less likely. Inflation hysteria was predicated on a small group of statistics and unusual factors (like hurricanes) driving them. With no perfectly clear picture of where things stood, imagination was left to run wild. And it did.

Things aren’t so confused any longer, or are substantially less so. There are good parts (like mining) of the economy and not so good parts (autos), like always. It may have seemed plausible that the economic direction could eventually work out more like the oil patch, those worries contained in auto and housing less worrisome so long as economic visibility stayed low.

The ongoing disappointments of 2018, however, have served to clear a lot of things up. Without another Hurricane Harvey or the upslope of trade wars the economy doesn’t look so great moving forward; more than that, the past year doesn’t seem so great on review, either. It’s no surprise that would lead to businesses fearing a setback while some actually do retrench and retreat.

Quite simply, at some point the boom had to boom if it was to be accepted as a real one. Businesses kept waiting for it to happen, and it kinda sorta seemed like it could happen for awhile. Without a more difficult tropical storm season or something beyond the crude oil sector really picking up, there’s only “overseas turmoil” left to focus in on. Not to mention the tightening noose of the purpose behind overseas turmoil.

It’s not recession tomorrow, but the next expected downturn is becoming more and more visible in economic numbers, too.

Stay In Touch