The politics of oil are complicated, to say the least. There’s any number of important players, from OPEC to North American shale to sanctions. Relating to that last one, the US government has sought to impose serious restrictions upon the Iranian regime. Choking off a major piece of that country’s revenue, and source for dollars, has been a stated US goal.

In May, the Trump administration formally withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, known otherwise as President Obama’s “Iran deal.” It was widely expected that pulling out would lead to harsh sanctions against any country continuing to trade using Iranian crude oil.

At the beginning of November, the US government formally re-instated those sanctions. In a surprising compromise, it did issue a number of waivers to countries like South Korea, Greece, Japan, and even China (among several others). That meant a good bit of Iran supply would remain available on global markets as a substitute source.

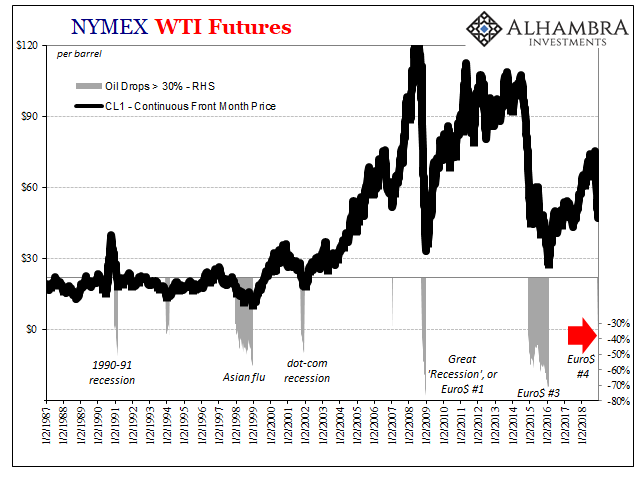

It is becoming 2018’s version of the 2014 “supply glut”, a benign or nearly so excuse for oil’s otherwise shocking crash. From Bloomberg only last week:

Just in late September, some traders were predicting that global oil prices would hit $100 a barrel over the following months. Their forecasts were based on the prospect of a supply crunch due to U.S. sanctions on Iran that went into effect in November. However, America’s surprise decision to grant waivers from its restrictions to some nations sparked a collapse in crude.

On the surface, the story does seem to check out; the US government did, in fact, keep Iran open for a little while longer. That additional future supply would have to have been factored into the ongoing oil price, further pressure to the downside.

But did it “spark a collapse in crude?” Nope, a demonstrable fallacy.

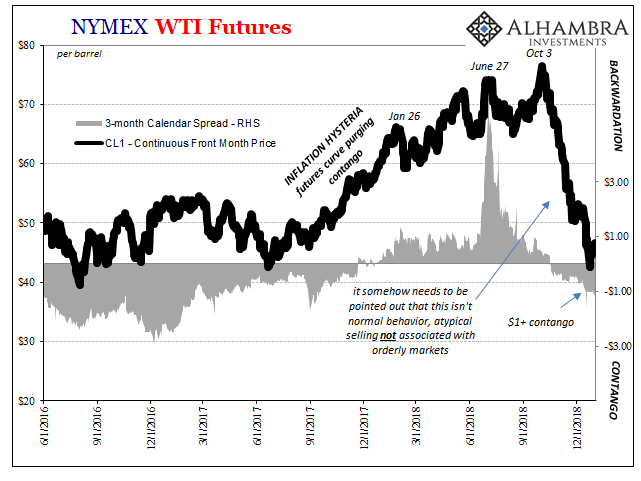

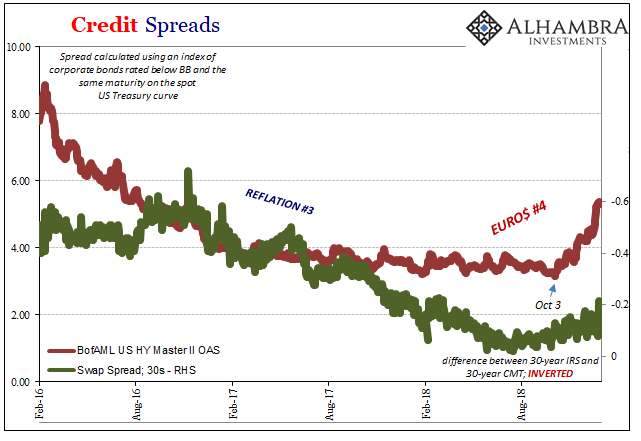

Oil prices peaked on October 3 and by the end of that month the curve was already weeks in contango. You could argue that global oil traders were counting on waivers and already factoring Iran into the equation, but again they were a “surprise decision.”

The drop in WTI and the chaos in oil markets (benchmark spreads) was more than a month old by then, and it’s been a straight line (almost) from the start of the crash.

In other words, Iran came along long after the market had viciously turned. Why is it so hard for people to accept that the problem could be rethinking demand worldwide?

It is, for many, impossible to believe that central bankers have it all wrong therefore the constant appeal of these sorts of ridiculous excuses. Mario Draghi says Europe is booming, or was, and if it isn’t now it’s only because of “transitory” factors to be cleared up soon enough. Jerome Powell can’t use the word “strong” frequently and emphatically enough in his commentary.

What do these guys know? A disorderly oil crash is uniformly associated with the opposite economic (and market) case. There is nothing benign about such open and obvious disorder.

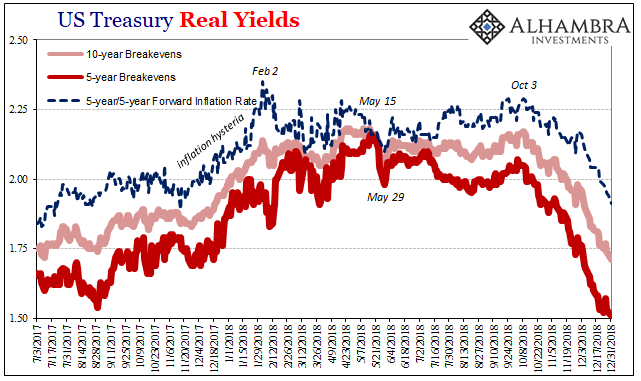

It’s not just the oil warning, though; there has been a predictable proliferation of denial, in my estimation just a bit more intense than the last outbreak only a few years ago. This is related to 2017’s inflation hysteria, the very flipside to it.

The idea of “globally synchronized growth” was deeply emotional. So many just wanted to believe that the upturn was actual recovery, and that the global economy had finally hit a growth patch after a decade without any. People still cling to the idea that central bankers are the “best and brightest” and therefore all that was missing was sufficient time.

The technocracy could never be denied its success. One full decade seemed to be the max allowable, therefore 2018 just had to be the one.

Except, trading last year produced one big warning after another, these accelerating and growing noticeably in the last half particularly the last two months. Rather than take account for them all, the excuses are always limited to trying to discount each warning individually. That’s a big clue about what’s behind them; emotion not rational analysis.

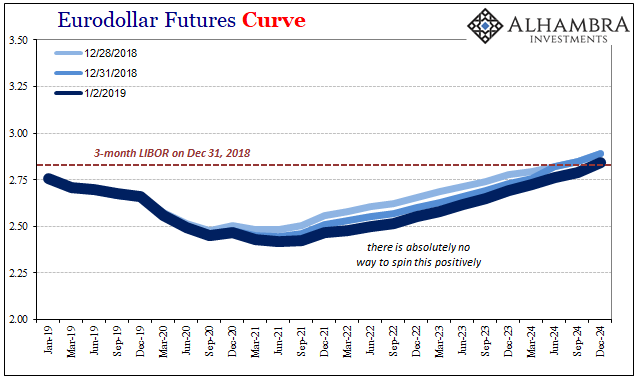

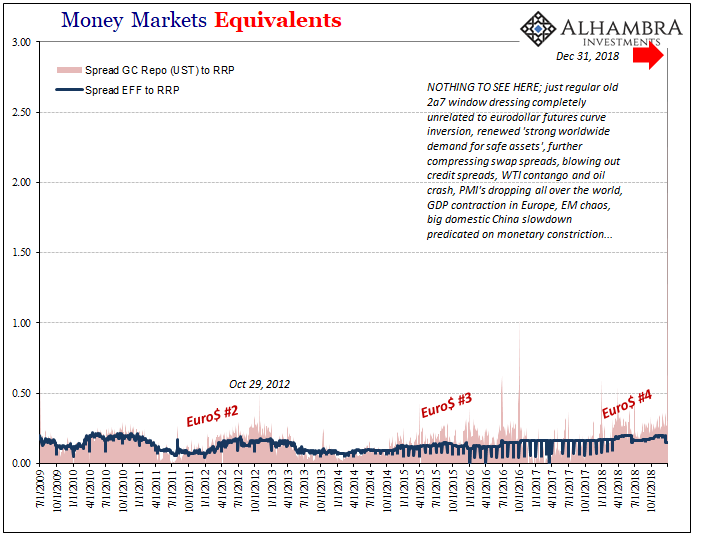

These are pure rationalizations based on pure denial. The oil crash must be a supply glut, but what about that ungodly repo rate spike? Well that’s just 2a7 year-end window dressing (yes, thanks L. Bower, some are actually trying to dismiss a nearly 300 bps spread in GC repo as no big deal, mere technicals).

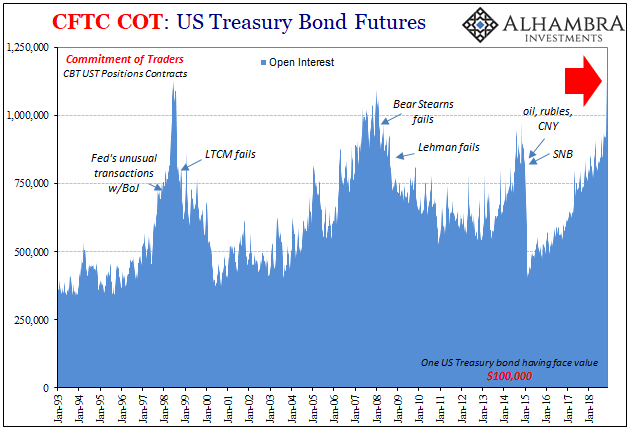

So, why does that repo spike oddly connect to exactly what eurodollar futures are saying? Or inflation expectations? Swap and credit spreads? UST futures (above) and the “strong worldwide demand for safe assets” that has intensified despite every major media outlet on earth declaring for more than a year how UST’s and German bunds are poised right on the precipice for a BOND ROUT!!!! of biblical proportions?

This is very comprehensive parade of deep, crucial markets all saying the same thing together – they really don’t know what they are doing. The world turned the wrong way (again), a surprise only to central bankers and those who still somehow believe in them.

That’s what always gets left out. Even if the repo spike, for example, was actually a product of 2a7, it still doesn’t get you to 300 bps. That level is alarming even in isolation. But it’s not in isolation, is it? You can’t (honestly) look at a market, even stocks, without appreciating corroboration and consensus for only darker and darker interpretations – all starting with liquidity meaning global money (including collateral flow).

If it was one thing you might listen about supply gluts or 2a7; when it’s everything, you can only ask yourself what’s the point? An unbiased review of all these markets (and more) paints a very grim view of where things already stand today. From this perspective, repo and WTI contango make perfect sense, neither really needing much explanation.

An oil crash or repo rate spike is intuitively self-explanatory, especially to these levels.

But Jay Powell is unshakable in his confidence. Therefore, Iran and supply glut. Or 2a7. Mixed signals. Etc. etc. etc. Nothing bad can ever happen, even all the bad things that keep happening.

Stay In Touch