A year ago, central bankers were over the moon. From those in the US to those in Europe, with Japanese officials in between, they really thought they had it. There wasn’t much basis for the belief, mind you, merely the fact that positive numbers were registering in all those places at the same time. Like some old Three Stooges movie, Moe (Powell), Larry (Draghi), and Curly (Kuroda) clunked their heads together and thought it had to mean something.

As 2019 dawns, nope, it really was meaningless nothing. Leading the way toward the wrong direction is Larry with Curly not far behind. Moe’s turn is fast approaching; he is currently paused to figure out whose face he might slap in order to shift the blame.

Curly always was the more flamboyant of the three. His track record for slapstick continues to be unmatched.

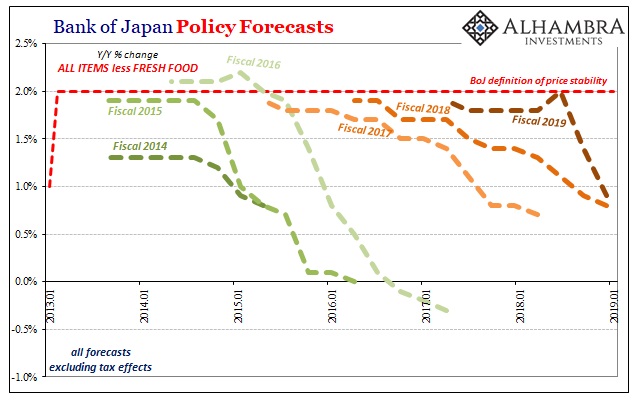

The Bank of Japan’s efforts to stoke inflation suffered yet another setback Wednesday when the central bank cut its fiscal 2019 inflation outlook for the third time in as many quarters, dashing hopes that its ultraloose monetary policy will end anytime soon.

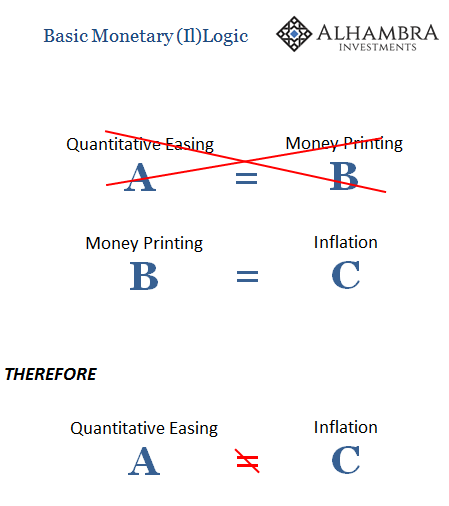

The Three Stooges worked because the audience was in on the joke. Economics is tragedy instead because it is pure farce. How in the world can “ultraloose monetary policy” suffer “yet another” setback along the lines of inflation? In a world where logic suffuses, it can’t.

The difference between January 2018 and January 2019 is immense, and it has nothing whatsoever to do with QE. From that we can easily and intuitively conclude Japan’s economic circumstances are not dictated by the Bank of Japan. Kuroda is the child sitting in the dark room testing his telepathy, intensely staring through the shadows in the unlighted direction of the light switch convinced he can flip it on with nothing more than a blink of his eyes.

When mommy enters the room and does exactly that, Kuroda focused on nothing else immediately attributes the light to his telepathic abilities. And when she turns it off on him frustrated by his foolishness, he goes back to believing his ultra-effective powers have only suffered a small setback. Kuroda really believes he will regain them again soon enough. The real question is, why does anyone else?

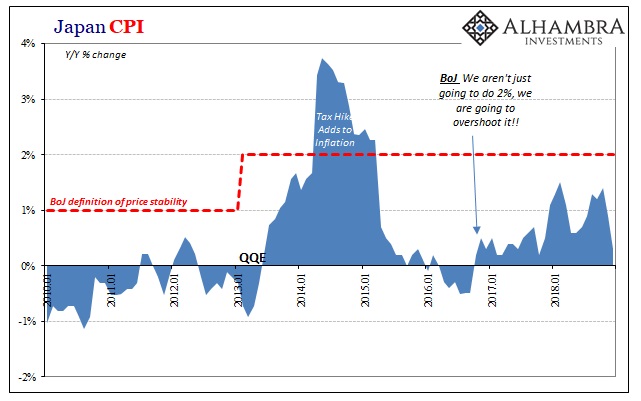

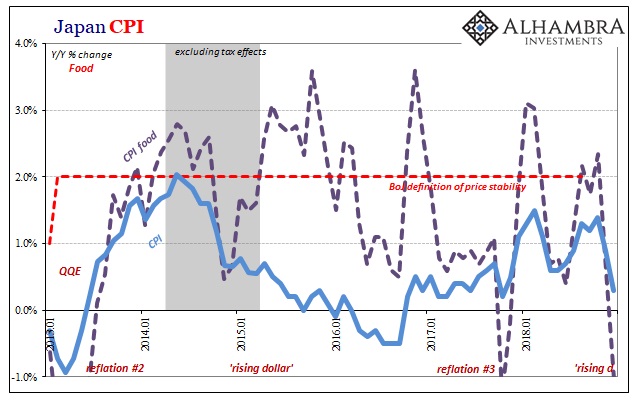

The Bank of Japan had no choice but to cut its estimates. Everything had turned against them in 2018. GDP contracted in two out the three quarters where it has been reported so far, and food prices are all that is left of the CPI. Food was up sharply twice last year, and still the CPI never got above 1.5%.

Food prices, according to the latest figures, dropped significantly in December 2018. Japan’s headline inflation figure was therefore just 0.3%. Core rates are down, too.

In January 2018, the BoJ was projecting QQE finally meeting its goal this year. As late as July, the main central bank statistical models were forecasting 2% inflation for Fiscal 2019. In a matter of six months, that has been blasted apart (what happened during those particular six months?) The BoJ’s updated central tendency released today is now just 0.9% – and that might prove optimistic still.

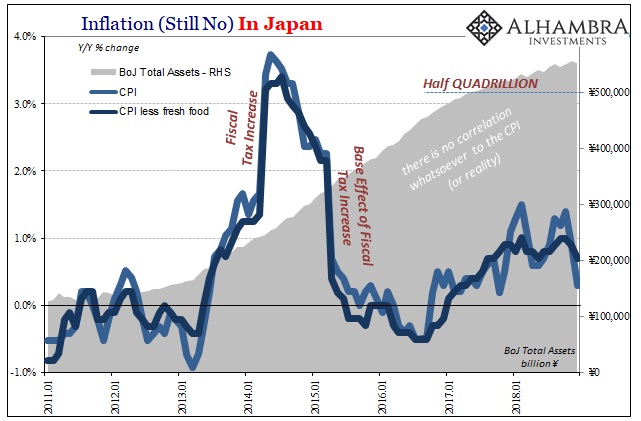

They really don’t know what they are doing. We follow and analyze Japan simply because it provides us with the most forceful evidence of exactly this fact. The central bank there is doing everything the central bank here (or in Europe) does but at a much higher level. QQE was Bernanke’s QE3 on steroids – a far larger percentage of GDP and carried out for almost six straight years (enlarged along the way, too).

The result? The US economy rises and falls in the same periods as Japan’s economy rises and falls. Despite all the “money printing” consumer price inflation almost always undershoots regardless in either place. Not a single central bank can maintain its inflation target no matter what it is they are doing or not doing.

The global economy is moved by the world’s reserve currency, eurodollar not dollar.

In 2017, it was slightly better so each economy moved over to small positives. In 2018, the eurodollar system flared up and now as we begin 2019 everything everywhere is pointing down. There are some minus signs already.

The way forward is equally clear. Stop calling it “ultraloose monetary policy.” It is moneyless monetary policy. The one thing the article quoted above got right, though, was “dashing hopes that it will end anytime soon.” Think about it this way, Japan again establishes the most important correlation – the more any central bank does the longer any economy goes without recovery or growth.

This doesn’t mean QE or QQE (with or without YCC) causes the economic deficit, rather it proves central banks are incapable of fixing the problem. They aren’t central. Therefore, they are the problem because they keep us from seeing what really matters. It’s the one place no one is allowed to look or question.

Japan’s been this way for just about three whole decades and nothing changes. We don’t have that much time.

My goal for this year is to get a moderator to ask “Is it morally appropriate for anyone to be a billionaire?” at one of the Dem primary debates. Ta-Nahesi just asked @aoc that question on stage at #MLKNow so we’re getting somewhere.

She said it isn’t btw.— Every Billionaire Is A Policy Failure (@DanRiffle) January 21, 2019

Stay In Touch