In January 2017, there was a lot of praise for Goldman Sachs especially in London. This stood in obvious contrast to another global peer being savaged. While Deutsche Bank couldn’t pull its name out of the sewer, GS’s London unit was heralded for standing up when the market needed it.

Brexit was a fascinating story in ways that had absolutely nothing to do with the politics. You look on any market chart and you can easily pick out when the vote happened. It was as much about pounds and LIBOR as it was the European Union.

Uncertainty is a liquidity killer. There is both a common sense reason as well as purely mathematical. If as a dealer you don’t know what you don’t know, you can’t deal. In terms of how balance sheets are actually put together, uncertainty is something like vol approaching infinity. Sheer paralysis; every position far too expansive and expensive to consider.

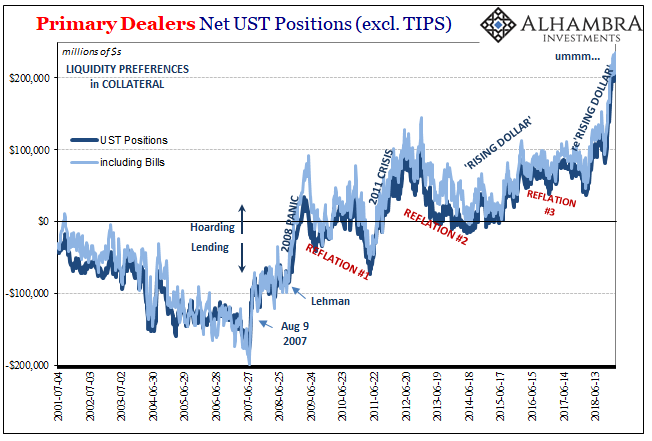

This is especially vindictive in the context of global funding; dealers depend on each other (incestuous) to lay off the risks of conducting regular functions. That’s what made 2008 (and the other Euro$ squeezes) so pernicious; the tendency of one bank to pull back immediately weakens the whole system. Redundancies, or what are thought to be redundancies, become bottlenecks.

It takes a whole lot to stand in front of uncertainty and fill the void (or what central banks are supposed to do, but can’t). In the two weeks before the Brexit referendum in late June 2016, the close election indicated a wildly unpredictable outcome. Liquidity started to become scarce.

For money dealers, if you do provide funding where do you lay off risk? Or do you take on risk yourself?

The cross-market nature of our product set allows us to offer better liquidity to clients than if we were simply showing a price and trying to find the exact offset in the market. If we see greater depth in the forwards market than the rates market, we may choose to hedge a client forward trade with a rates trade. Warehousing this basis risk between the two markets allows us to offer the best liquidity to clients and minimise our execution footprint.

I’ll translate for Beth Hammack, at the time she gave this quote Goldman’s head of global repo and short-term macro. Goldman took on the risks of funding uncertainty (warehouse) because they saw an opportunity in doing so. Even after Brexit, Goldman was providing dollar liquidity in London absorbing by some accounts massive risk (some reported with DV01 of £1 million) to do so.

Mrs. Hammack chalked it up to her unit’s creativity and more expansive mandate. In end, the “bank” used its balance sheet capacities because they were betting on reflation. Whatever ultimately the consequences of Brexit, a booming global economy would make up any difference. Time was a key component, as one dealer counterparty (borrower) admitted.

A senior member of the UK bank’s treasury team credits Goldman’s proactive approach, willingness to provide capital – particularly for the cross-currency swaps – and the set-up of its short-term macro group for the success of the trades.

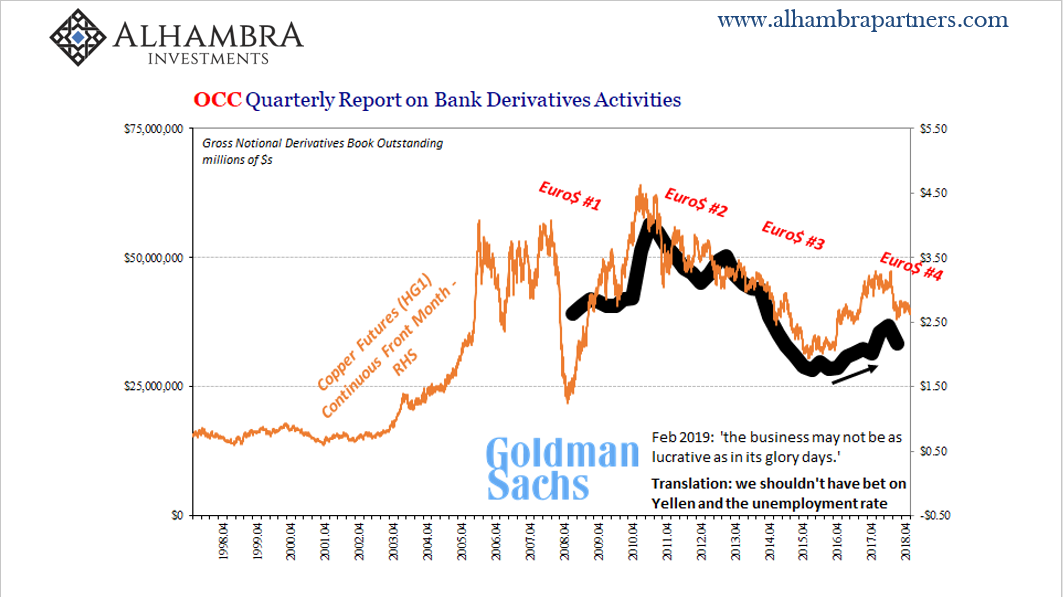

For that they were celebrated – in January 2017. As noted several times last week, things are quite different in February 2019 for Goldman. The willingness to provide balance sheet capacities in these sorts of FICC maneuvers has suddenly disappeared. What changed between then and now?

Reflation, obviously. How many times over the last three months of 2018 did dollar-starved counterparties look to Goldman for a reasonable lifeline? How many times did the “bank” get creative and instead set up the short-term macro group for expensive missteps? Too many, clearly.

Mrs. Hammack was promoted for her efforts, moved upstairs long before whatever specifically might have gone wrong in December. Now the firm’s global Treasurer, she is also co-chair of the Firmwide Finance Committee. Having obtained a degree from Stanford in Quantitative Economics, she fits right in.

Not only does she sit in a very high position within her firm, Mrs. Hammack had been named the Chair of the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC). This latter group is made up of Wall Street bankers who advise the US Treasury department as to its funding and debt servicing requirements.

About two weeks ago, in her capacity as Chair Mrs. Hammack wrote to Treasury Secretary Mnuchin reporting on the committee’s recent work. It’s the usual stuff; strong economy but a lot of debt. It’s a long report, but I stand by my summary. The usual Economist talking points.

What worries the TBAC the most is, because of the strong economy, there may not be enough demand for UST’s. Yes, she wrote this letter not even two weeks ago.

The presenting member estimated borrowing needs to exceed $12 Trillion without factoring in the possibility of a recession which would pose a unique challenge for Treasury over the coming decade. Additionally, given stagnation in international reserves, there is likely an increased need for this debt to be financed domestically. This blue sky discussion, in the context of the optimal debt model, focused on the need to expand demand, while preserving the key tenets of regular and predictable issuance at the lowest cost to taxpayers over time.

China is selling, for reasons she very obviously doesn’t understand, the US economy will still be booming, and so the Secretary has quite the problem on his hands. It is, apparently, always reflation for Economists.

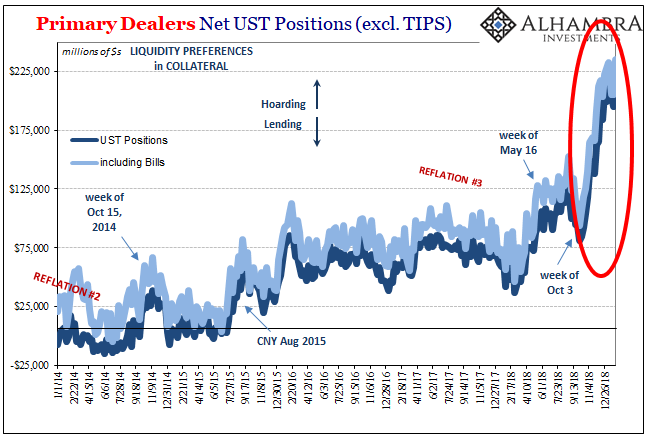

A recession would certainly pose a unique problem, but not to the Treasury Department’s debt function. This is the very thing that the interest rates have nowhere to go but up crowd never seem to register; financial participants, including Goldman Sachs at times like these, are heavy into buying and hoarding UST’s because the US government’s fiscal problems are way, way off over the horizon.

Whether the federal government ever is held to account for its massive accumulated debt is just too far away to matter right now. The call from BONY Mellon could be tomorrow. You better have collateral on hand before the phone ever starts ringing. It seems like someone who ran global repo for a major bank would appreciate the real logistics of the repo (and derivative) books at major banks. Then again, Stanford degree in Quantitative Economics.

There is, however, an often serious disconnect between “running” the repo desk and actually running the repo desk. I’ve run across this disparity quite a lot; big bank management is very often made up of either formal Economists or those who are dazzled by the quant capabilities of formal Economists. Traders, those who see the real world, and are held to account for being creative under an expansive mandate when reflation “unexpectedly” disappears, might end up doing something altogether different.

In other words, a senior official at Goldman is openly worried about demand for UST’s when in every likelihood the desks at Goldman are going to (keep) fill(ing) it. Mrs. Hammack steadfastly adheres to reflation, actually way beyond reflation to this unbelievably booming economy of her specific description. Who was it that was hedging deflation/recession risks while she was writing this report? The very bank burned on her reflation.

Long before the federal government ever has to worry about running out of bidders for its paper, it is going to have to deal with the economic fallout of still another episode where (global) monetary capacities have been neutralized by the same expectations for recovery and growth falling apart. That’s political not financing risk. Economists are the last to figure this out. Even long after the banks have equalized to a very different perception.

Stay In Touch