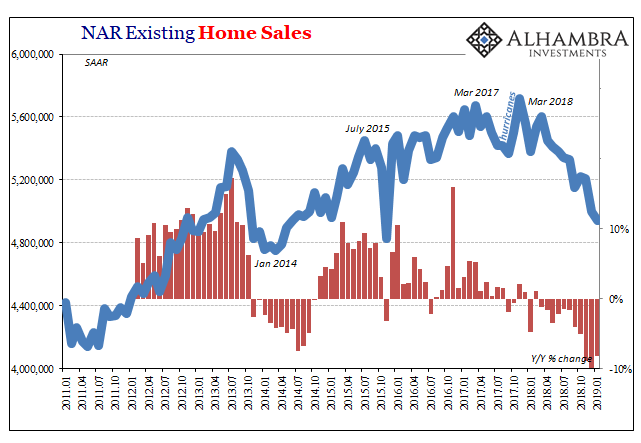

For years, realtors have been waiting for more housing inventory. It had become an article of faith, what was restraining a full-blown recovery was the lack of units available. The level of resales like construction was up, but still way, way less than it was now fourteen years past the prior peak despite sufficient population growth to have absorbed the previous bubble’s overbuilding.

All the way back in March 2017, the National Association of Realtors (NAR) was lamenting the low number of new listings. Chief Economist Larry Yun would begin to use what became his standard (attempted) answer:

Realtors are reporting stronger foot traffic from a year ago, but low supply in the affordable price range continues to be the pest that’s pushing up price growth and pressuring the budgets of prospective buyers.

It was more than a thorn in the side of the real estate business. It was an enigma; after all, the economy was booming, they said, so it was a mystery as to why the combination of that plus sharply rising home prices wasn’t convincing hordes of home owners to cash in.

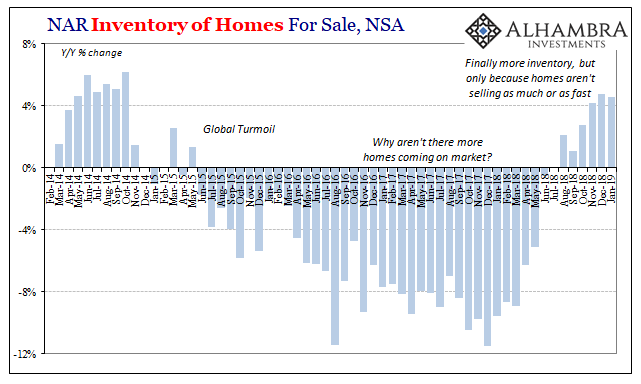

Beginning in the middle of 2018, realtors finally got their wish. Sort of. Inventory levels are rising, the count of homes available for sale up year-over-year for six months in a row through January 2019. Whereas there had been just 3.7 months of supply on offer back last March, last month, the latest estimates available, supply has jumped to 4.4 months’ worth.

Instead of rejoicing, those in the housing business are now very concerned. They could convince themselves that those several years of falling inventory were due to some unrelated factor, an exogenous, transitory quirk a very healthy economy would clear up and overcome given enough time.

Today, however, the increase in inventory is not that; it instead coincides with the slump in sales.

Reluctant home owners haven’t plunged in from off the sidelines. Quite the contrary, they remain just as wary as ever. As the housing market turns negative, what little was available for sale is now piling up, unable to be sold and pushed off market fast enough.

It was supposed converge in the other direction, meaning higher and higher sales plus higher and higher prices supplied by more and more optimistic home owners finally seeing the economic benefits of a booming system. The virtuous circle complete, just in time to coincide with globally synchronized growth.

Sales are now syncing down with low levels of inventory. It’s not quite the rebalancing everyone’s been waiting on.

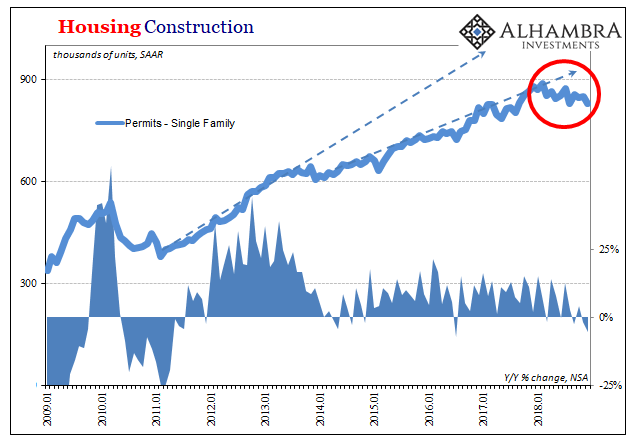

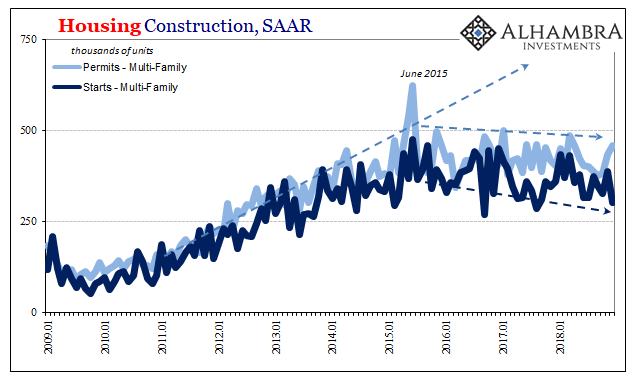

This is the case across the entire real estate sector. Home construction has turned lower, too, as builders are left to reassess what’s really going on.

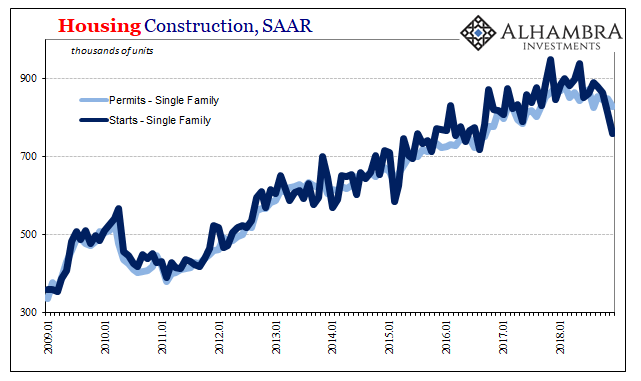

In the single-family sector, the number of permits filed to build new units has steadily declined since last February. Meanwhile, the number of new homes actually beginning the construction process, starts, had plunged over the final four months of 2018 (the latest data from the Census Bureau, released today, updates construction estimates through December 2018). Not surprisingly, the inflection toward this negative turn began after last May.

The sharp drop in starts in both November and December suggests something other than anticipated imbalances in physical supply and demand. Given what we know of market action during those two specific months, particularly the last one, this suggests financing issues on top of growing fundamental uncertainty. It doesn’t cost much to file a permit, but you have to have credit in place to begin construction.

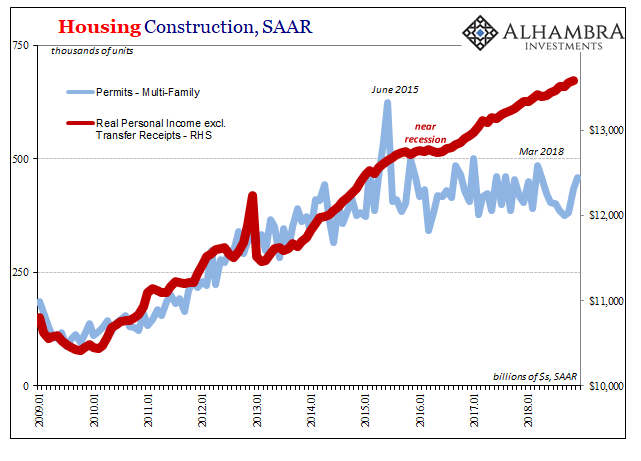

The lackluster pace of apartment construction has matched the pattern in resale inventory, establishing the real economic baseline underneath all these changing conditions. Ever since the last downturn in 2015-16, Americans have been reluctant to move around; to the point that they’ve conspicuously avoided it. Unlike the unemployment rate, this cautious behavior fits the income data perfectly. If your own experience of the labor market doesn’t match the boom Larry Yun keeps talking about, especially what you can see around you, the last thing you are going to do is sell your house if you own one, or move into your own apartment if you don’t.

The housing market like the overall economy has been largely bifurcated for more than a decade. The proportion of those who aren’t doing well has remained unusually large. Full and complete economic recovery, no matter how long it might’ve been delayed, was supposed to shrink their number considerably. Globally synchronized growth and the US unemployment rate supplied some evidence this was finally happening.

But that’s not what the housing market data was really suggesting (or the labor data beyond the headlines, for that matter). Now as 2019 begins, we are facing the opposite prospects. It seems as if there are very real concerns the group left out of economic growth might actually grow again instead of the economy. People haven’t been selling homes, renting new apartments, and now they aren’t buying, either.

There was only ever an illusion of an economic boom. More and more it appears there’s not even the illusion.

Stay In Touch