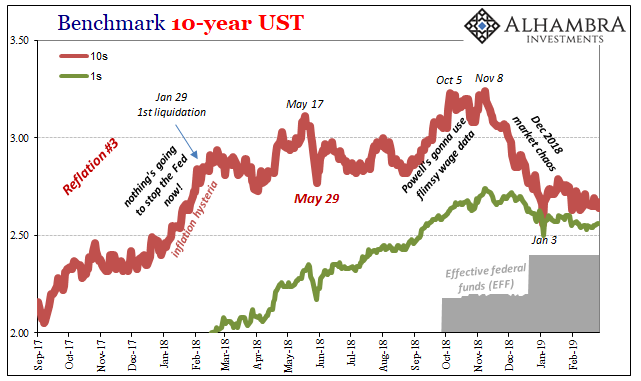

What gets them into trouble is how they just can’t help themselves. Go back one year, to early 2018. Last February it was all-but-assured (in mainstream coverage) that the US economy was going to take off. The bond market, meaning UST’s, was about to be massacred because the overheating boom would force a double shot down its throat.

Not only would safety instruments like UST’s have to contend with the unemployment rate, and therefore wage-driven inflation just ahead, the Federal Reserve would have to get more aggressive to head off the worst parts of what Economists call an overshoot.

On March 1, 2018, Chairman Powell still new to his job appeared before the US Senate Banking Committee. It was his first Humphrey-Hawkins required testimony, a commitment many were using to judge the character and thinking of Janet Yellen’s replacement. When he was done, everyone, and I mean everyone, said he had been hawkish, fitting the hysterical inflation narrative perfectly.

Two days before, Mr. Powell testified in front of the House Financial Services Committee how inflation was his biggest concern. To the assembled Senators, he quite purposefully started by walking those comments backward. Remembering his Greenspan, Powell remarked:

We don’t see any strong evidence yet of a decisive move up in wages. We see wages by a couple of measures trending up a little bit, but most of them continuing to grow at two and a half percent. Nothing is suggesting to me that wage inflation is at a point of accelerating. I would expect that some continued strengthening in the labor market can take place without causing inflation.

So far, so good. His assessment here was accurate. There was, even at the end of February 2018, amidst all the craze, no evidence for an inflationary shift in the US economy let alone one so pronounced it would force radical changes in major factors.

Unfortunately for the Fed Chairman, he wouldn’t leave it at that.

At this point, we have 4.1 percent unemployment. The things we don’t want to have happen is to get behind the curve, have inflation move up and have to raise rates too quickly and cause a recession.

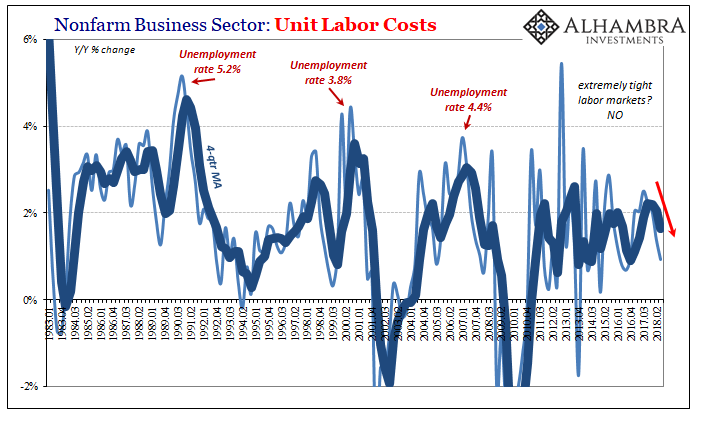

From pragmatic and data-dependent to unhinged but supreme hawk in a matter of minutes. Policymakers were, and are, absolutely dazzled by the atypically low unemployment rate. Even for all its faults and complications, it is just too tantalizing to set aside no matter how much logic intrudes upon it from the distinct lack of corroboration.

What’s worse for the FOMC, this is not a new development. There’s been no evidence for years on end. Janet Yellen’s entire four-year term was carried out under the same exact inflationary cloud of suspicion. The only reason policymakers chose to believe something was different, better different, in 2017 was time. It was running out on them and so that’s what the unemployment rate did.

It was the only thing that might suggest QE had worked and Economists were right about something. They latched onto it merely hoping that at some low level it would trigger the inflationary recovery scenario. This was emotion, not rational analysis. Powell was reasonable in his first quote above, and daydreaming fantasy in the second.

Guess which one received the most attention. The latter was framed, as always, like the steady forecast of a seasoned, wise expert. It couldn’t have been farther from the truth. Most people never heard anything about the evidence.

As we close in on March 2019, we are still waiting for some of the lesser-known labor market data for the last quarter of 2018 (the BLS being forced to reschedule data releases due to the shutdown). No matter. What estimates we have already more than prove Powell’s original sentiment; there has been no evidence for “a decisive move up in wages.”

It’s not there and it hasn’t been.

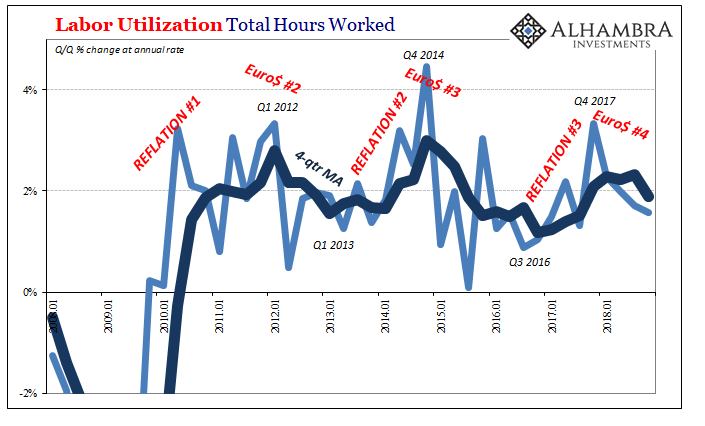

Starting with the BLS figures for Total Hours Worked, the gains in what amounts to overall labor utilization have followed the familiar rhythm – eurodollars, not Federal Reserve. This includes, ominously, the growing sense of slowdown attached to Euro$ #4.

Revised estimates (through Q3 2018) show labor utilization growth slowing substantially since Q4 2017. This matches widespread observation especially abroad suggesting the whole global economy hit a monetary brick wall to begin last year. The US wasn’t booming even all by itself, that was just unsubstantiated talk about what many were hoping might happen in the future (if everything went right; it was an absurd expectation given how much was already going wrong).

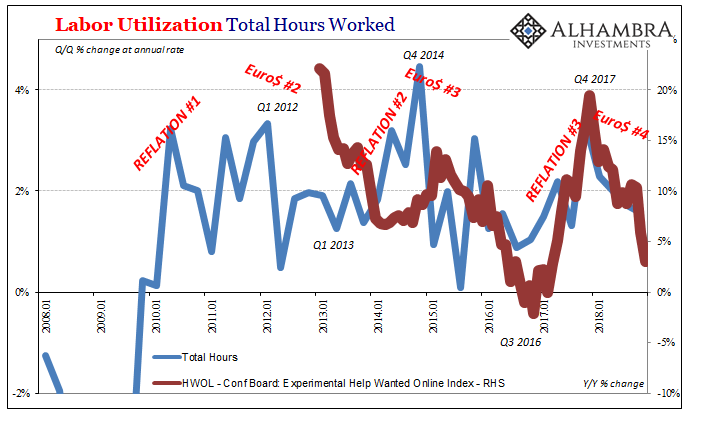

Of the very few statistics looking in the same direction as the unemployment rate, JOLTS measure of Job Openings has been on such a tear it nearly disqualifies itself as an obvious outlier. Therefore, is there really a conundrum: labor utilization is falling according to the BLS at the same time demand for new labor is sharply rising also according to the BLS.

As noted before, however, other independent measures of the same thing, labor demand, have suggested what the Total Hours series does. The economy spent much if not all of last year slowing down (from a peak in 2017 that wasn’t all that high to begin with), labor market included. This would, obviously, be much more consistent with “muted” inflation since wage and labor costs never really sparked. If both demand and utilization are flagging, this would explain a lot more than Powell’s late-2018 U-turn.

In fact, several other figures on them indicated a significant degree of decelerating rather than accelerating labor costs. At best, there wasn’t anything consistent with a very tight labor market, certainly nothing like inflation hysteria’s chief outburst, the once-ubiquitous LABOR SHORTAGE!!!

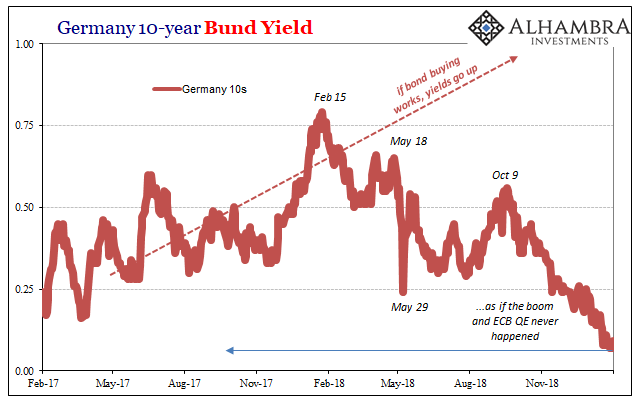

The funny thing is, Mario Draghi, head of Europe’s central bank, a month or so earlier he had said pretty much the same thing as Jay Powell did at the start of last March.

The strong cyclical momentum, the ongoing reduction of economic slack and increasing capacity utilisation strengthen further our confidence that inflation will converge towards our inflation aim of below, but close to, 2%. At the same time, domestic price pressures remain muted overall and have yet to show convincing signs of a sustained upward trend.

We have no reasonable basis to believe it, and we’ve been wrong about this for years on end, but trust us this time it is really going to happen!

More than anything, this is why I consistently called it inflation hysteria. Like an outbreak of mass hysteria in any other setting, there was at root nothing to it, an entirely (and visibly) irrational approach to an issue of supreme substance. Central bankers were forced to admit it, before then quite purposefully abusing their pedigrees in a last-ditch effort to avoid another (very predictable) failure.

This week, Powell’s message is very different – in the second part. The evidence continues to be the same. Muted inflation and “some crosscurrents and conflicting signals.”

Globally synchronized growth was never a real thing. Both Draghi and Powell can claim they acknowledged the evidence, but that really doesn’t absolve them of their intentional, baseless hawkishness. This is what expectations-based policy has done in the absence of actual monetary competence.

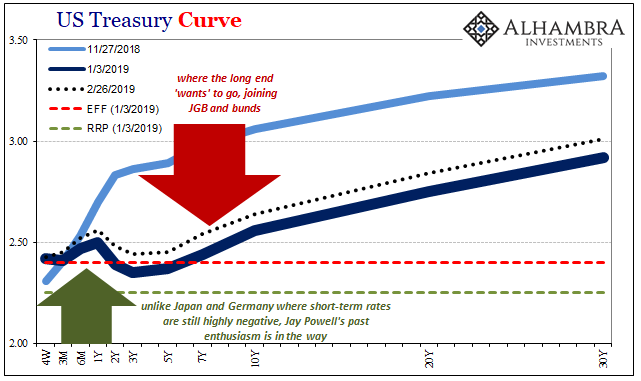

It is the implications of all this which global bond markets are pessimistically trading against, ruthlessly unwinding the surreal imaginations behind the hawks; including, as discussed earlier today, what’s holding up the long end of the UST curve. For now.

Stay In Touch