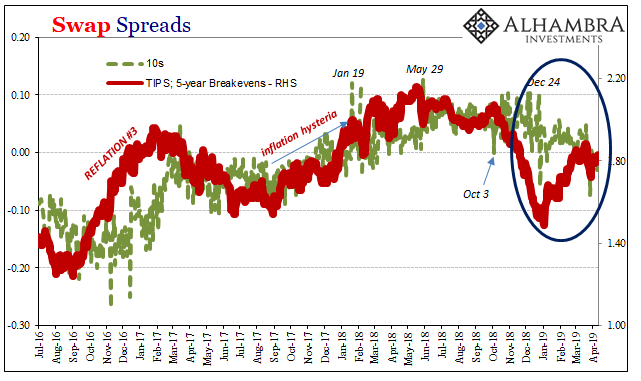

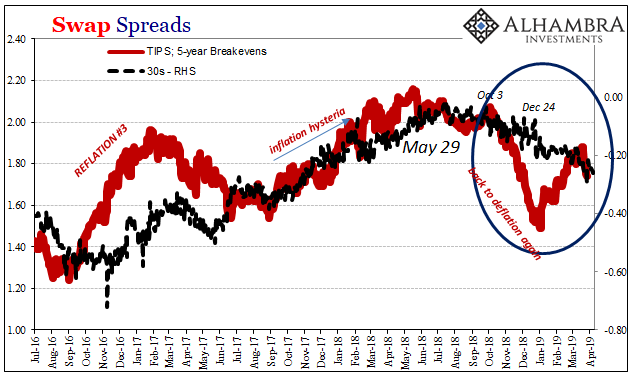

May 29. May 29. May 29. It keeps showing up everywhere. Not only does it appear as an inflection on so many important market charts, we keep finding it in economic accounts, too. There is so much to corroborate what can only have been a real and striking event.

This contrasts, of course, with the mainstream narrative. Last year the US economy in particular was incredibly strong. Or, that’s how it was described even after that date. At one point, referring specifically to May 29, the FOMC purposefully tried to suggest the bond market was mispricing the real economy. From their view, there was no reason for another intense burst of “strong worldwide demand for safe assets.”

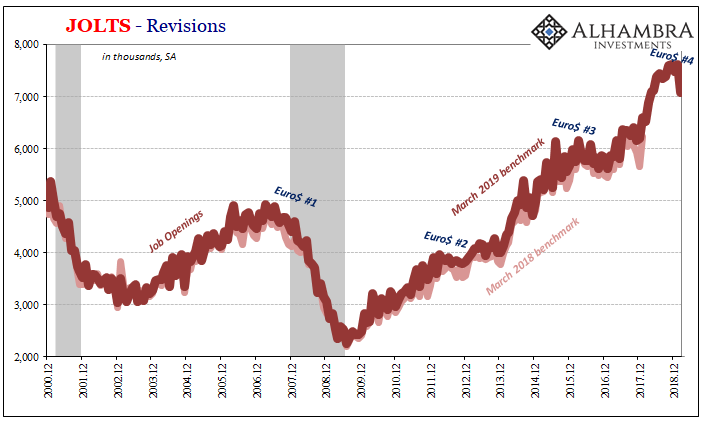

One of the primary reasons to dismiss that demand was (a few) labor market statistics. The unemployment rate, yes, but also JO, or Job Openings. This JOLTS series portion which tries to estimate demand for labor (independent of supply) was famously incorporated into Janet Yellen’s economic “dashboard” where it has remained.

Why it has remained is up for debate. There are very real questions surrounding its legitimacy, particularly in the wake of “muted” inflation.

What JO purported to show was a scorching labor market last year. No wonder, then, why it stayed high up on the list of dashboard material. The unemployment rate was awfully lonely in describing the same economy Jay Powell was.

However, JO also asked us to believe that things were indescribably good. As late as for November 2018, Job Openings were increasing by more than 20% year-over-year. Does anyone really buy that? Other than the financial media.

There is the very real possibility that like the unemployment rate, JO is being led astray by structural changes. There isn’t more demand for labor, as a rise would have it, businesses may simply have to advertise more to fill the same number of open spots.

Even if you do believe JO is accurate enough, there are now warning signs which have materialized in the data. Job Openings in the latest month, February 2019, plummeted by more than 500k (seasonally-adjusted). That by itself may not be too concerning, the series is noisy and volatile, subject to revisions on a monthly basis.

If weak estimates keep appearing, then it might suggest more definitive conclusions.

What gets our attention in the meantime is more how the rate of change has itself changed. Dating back to last summer, around July 2018, JO was up just 2% to January 2019 (not counting February’s big dip). If you think JO is accurate on the way up, something seems to have changed since the boom.

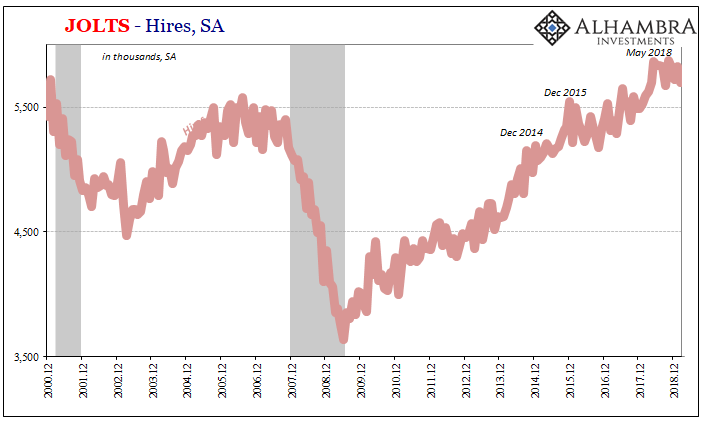

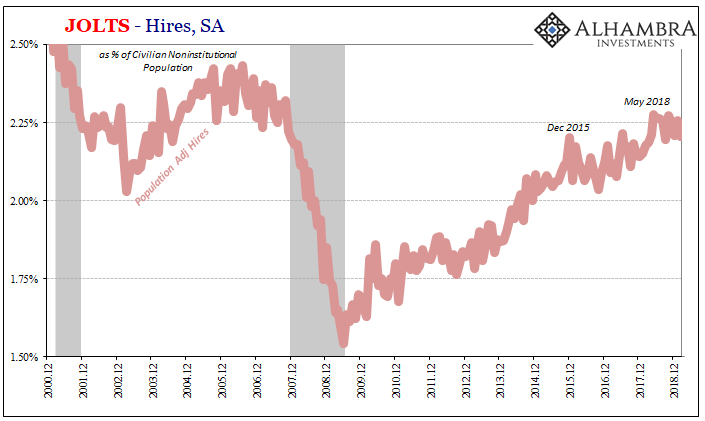

The better part of JOLTS, HI, or Hires, is perhaps the series which should have taken JO’s place on the dashboard; particularly if you properly calibrate the monthly rate to the size of the population. It more closely approximates and corroborates what we see everywhere else, particularly the still-historically depressed increases in wage rates.

That debate aside, there is consistency even with JO about the last almost year or so. According to revised figures, the rate of hiring in the US economy had at best plateaued throughout the bulk of last year and may have started to decline. When did the labor market reach this potential inflection? May 2018.

Count May 29 on yet another economic account.

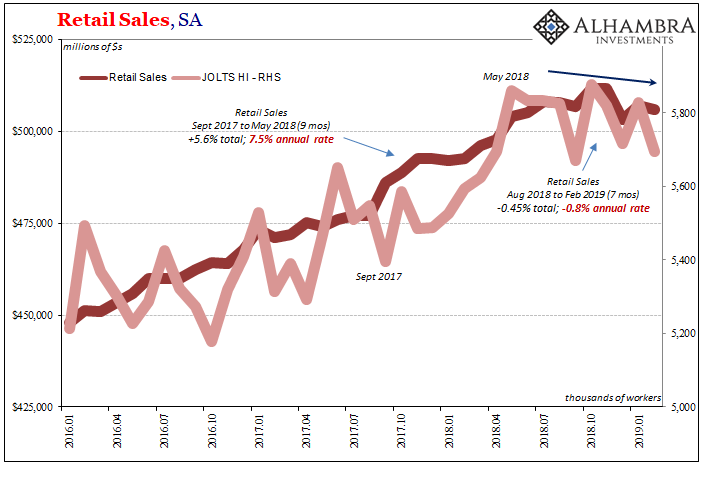

This is therefore quite consistent with the data we see elsewhere, just as it should be (unlike JO). If businesses for whatever reasons become noticeably less willing to hire new workers, workers might tend to notice this change (in the aggregate). And if enough workers perceive a material softening here, at the margins as consumers they may begin to spend a little less as their uncertainty persists.

Some who were expecting to find work may spend a lot less as they figure companies aren’t hiring like they used to (which, as the population-adjusted series shows, wasn’t all that robust to begin with).

May 29 wasn’t Italian populists, it was a full-on eurodollar break. What’s more, or less as these cases show, despite all the recent talk of “green shoots” the world remains stuck on the May 29 track.

Stay In Touch