When central bankers use the word “financial” in an economic context, they mean exclusively stocks. Maybe that’s somewhat appropriate given how bonds are so often treated as monetary equivalents. Then again, if that is the case in the official view, how does anyone reconcile bonds with anything? Economy or money?

The hard answer is that officials don’t really care about yields. They “decompose” them into what they think are discrete components and then analyze the yield sausage as needed. What that means is while falling yields to the rest of the world signal serious trouble, in central banking circles it can mean a number of other things.

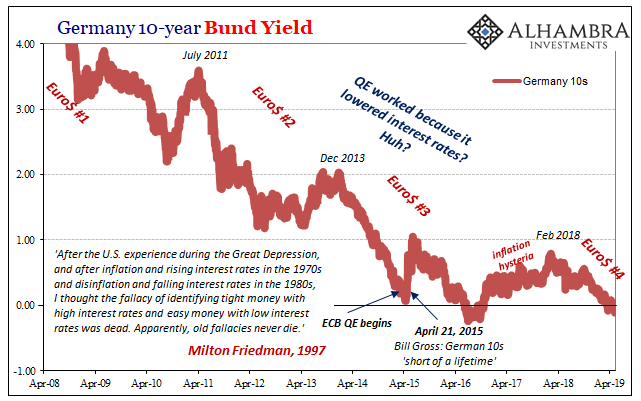

This Fisherian exercise is another one of those which leads toward self-delusion; you end up seeing what you want to see because you really, really want to see it. The most infamous example was Ben Bernanke opining on his own tenure. QE was supposed to have lowered long-term interest rates and that was supposed to have been stimulus.

Yet, interest rates fell more without QE than with it. Forget Friedman’s interest rate fallacy, how does Bernanke explain just that one starting inconsistency? Term premiums.

In early 2015, the by-then former Federal Reserve Chairman attempted to explain the contradiction using them. The economy was booming, he declared, as such Janet Yellen had just ended “bond buying.” Bernanke wrote:

What about the decline in longer-term yields since early 2014? In the US at least, that decline is somewhat surprising, as economic fundamentals have recently seemed more consistent with rising, not falling, longer-term yields. The year 2014 was a good one on the whole for the U.S. economy, with three million jobs created, and longer-term inflation expectations appeared to remain stable. By the process of elimination, with fundamentals stable or improving, much of the decline in yields over the past year must reflect a sharp drop in term premiums.

Falling yields couldn’t possibly signal something bad when the world was nothing but good. Therefore, term premiums.

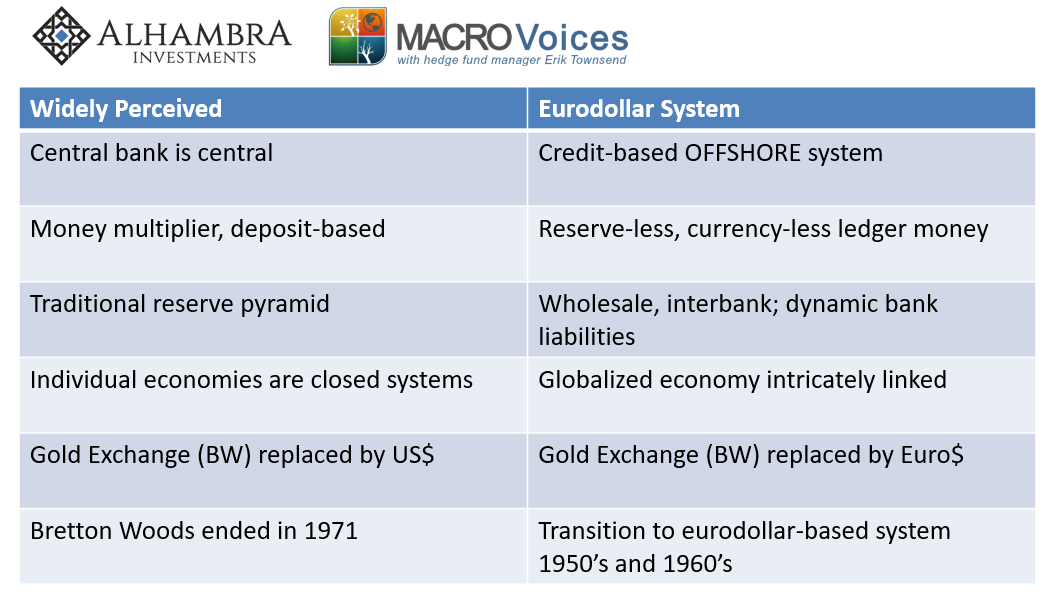

These are something only Economists do because they don’t understand bonds. And they don’t understand bonds because they begin by thinking backward: the central bank is central, as such everything the central central bank does is by definition stimulus. Monetary policy acts, bonds obey.

And when they don’t, they still do because…term premiums. It is, again, desperately delusional.

It wasn’t the first time for Bernanke, either. As I wrote a few days ago, the only thing that stands still in this world is Economics. In attempting to answer for his predecessor Alan Greenspan’s bond market “conundrum” of 2005, in 2006 Dr. Bernanke would blame misbehaving long yields on, say it with me, term premiums.

I bring this up constantly, Economists don’t understand bonds, because officials are doing themselves and the rest of the world huge disservice by never bothering to reconcile their dogma to what is the biggest, deepest, most accurate, as it turns out, markets the world has ever conceived.

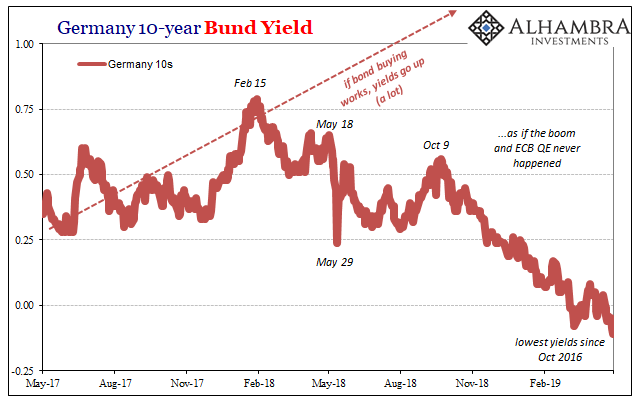

The current set of superstitions obviously preoccupy more than our own American central bankers. We are now confronted with a global slowdown maybe already worse. This is not, as they will print in the media on word of these central bankers, unexpected. Rather, the world’s bond markets have been pleading for attention for well over a year now.

If anything, the bond market warnings have only escalated. In response to them, official acknowledgements have, too; only, they are quite literally behind the curves. And they are dragged into them kicking and screaming.

First, the economy was booming even after bond markets changed especially in Europe, especially the key one in Germany. Then, after being faced with a rough end to 2018, officials belatedly admitted to a “soft patch”, but only a temporary one. Nothing more, they reassured the world.

With yields still falling a third of the way through 2019, OK, it’s still a soft patch, though perhaps not as transitory.

The Federal Reserve released the minutes from its last policy meeting in April this week. The European Central Bank did the same thing yesterday. In the ECB’s Account of the Monetary Policy Meeting for April 9-10:

Looking further ahead, members widely shared the view that the more protracted “soft patch” suggested by the latest data remained consistent with the baseline scenario of a return to more solid growth in the second half of the current year. At the same time, it was acknowledged that there was now somewhat less confidence in this baseline scenario and that the range of other possible outcomes had widened. [emphasis added]

The Members then discussed the external nature of the slowdown, how it seemed to be coming to them via global trade. But then they apparently convinced themselves how that must be a good thing, somehow.

However, it was also remarked that “soft patches” in economic growth had been observed on numerous occasions and that historical data implied a low probability of them turning into recessions. Reference was made to a number of positive indicators and supportive factors. The service sector had remained more resilient than manufacturing. Financial market developments, which were typically more forward looking, were more upbeat.

“Financial market developments…were more upbeat.” Which ones were those, exactly? Not bonds, obviously, only stocks. Unless you deconstruct bonds into what you want them to say.

These presumed authorities don’t even realize how they are being led to their own conclusions following behind the bond market in the face of stocks’ almost unrelenting positivity. At each and every forecast downgrade, they fail to acknowledge how bonds were right about the downgrade and then still look to stocks for what the next change in forecast should be.

Like Ben Bernanke in early 2015, they then fool themselves into believing bonds are actually agreeing with them through the pure sophistry of something like term premiums. This is so much more than the interest rate fallacy, it is a rotten system that is producing very real harm in the world.

In Europe, the boom just fizzled and now the ECB Governing Council is talking about recessions again. In the US, the Federal Reserve can’t make heads nor tails of how rate cuts are being projected and soon. In China, well, the less said the better.

Not only is the bond market pointing in the right direction, it even tells the world the very reason why it’s all coming apart. Again. It’s a damn roadmap. The world’s best and brightest, though, they can’t read it because they absolutely insist they are not holding it upside down.

Stay In Touch