We have arrived at revisions season once again. It’s that time of year when many if not most (I don’t actually keep track) of economic accounts undergo heightened scrutiny. More data is collected from more comprehensive surveys using far larger samples. These are compared to the existing high frequency panels and changes are made as necessary.

Sometimes these are substantial, as we’ve been noting for the past half-decade or so. As is the tendency near always on the downside.

This year is going to be a little different. For reasons I’ve yet to see, the 2017 Economic Census, the mother-of-all-data-panels, isn’t scheduled to filter its way into the figures. That won’t start to happen, as I understand it, until next year.

What that means is annual revisions in 2019, apart from specific series with their own annual panels, will be about seasonal adjustments. These need to be updated, too, though they tend to be much smaller and less significant on their own.

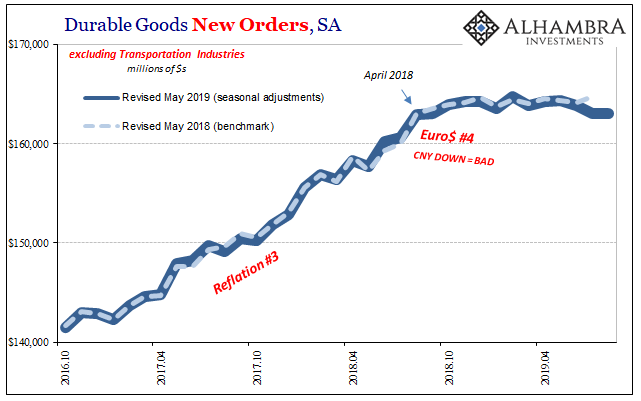

The first following this pattern is durable goods. The unadjusted series has been left unadjusted, untouched because there was no benchmark change. Only the seasonally-adjusted data is updated by small shifts in those particular components.

In terms of new orders for durable goods (excluding those booked by transportation industries), the revisions have added a slight negative to what had already been a curious sideways trend. Since the unadjusted figures weren’t revised, the bend in the trajectory still lines up at April/May 2018.

I don’t think that will change at next year’s benchmark, either. Rather, it seems more likely, in my view, that durable goods (as other accounts) might be revealed to have had more of a downward skew. Something more consistent with the recent past.

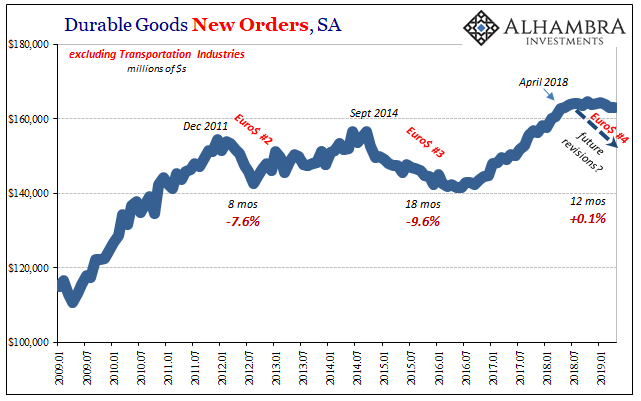

But that’s just speculation. What we know right now is that the manufacturing sector has been in something more than a slump and what’s currently figured to be something less than the other “manufacturing recessions” of the last decade.

It is still consistent with a slowing economy and therefore a distinct lack of decoupling from “overseas” weakness – particularly the timing coinciding with the clear outbreak of “overseas turmoil”, CNY DOWN, and May 29.

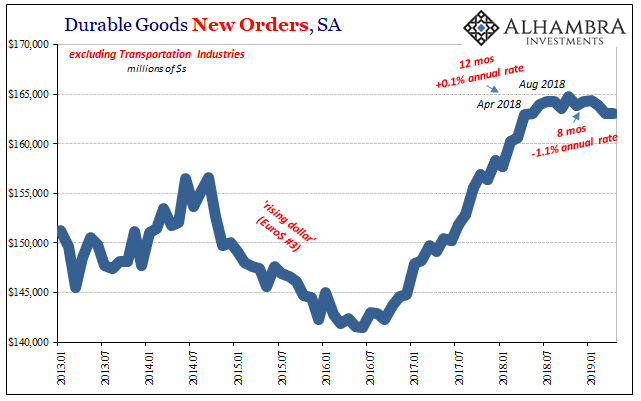

Going back to last July, beginning with August 2018 durable goods orders are falling at a 1.1% annual rate. It might not be recession but it’s certainly not consistent with the “strong” economy sporting a sub-4% unemployment rate labor market.

Something obviously isn’t right. Since this inflection extends now a full twelve months, an entire calendar year, it’s not likely to be “transitory.” Unless you are a central banker, the word transitory means temporary and no reasonable, honest person would think the word applicable to a period lasting a full year.

Unadjusted, durable goods orders were positive though up just 1.4% in April 2019 from April 2018. That follows a downward revised (short-term revisions) 0.2% year-over-year gain in March. No minuses yet, though the trend is quite clear on that account.

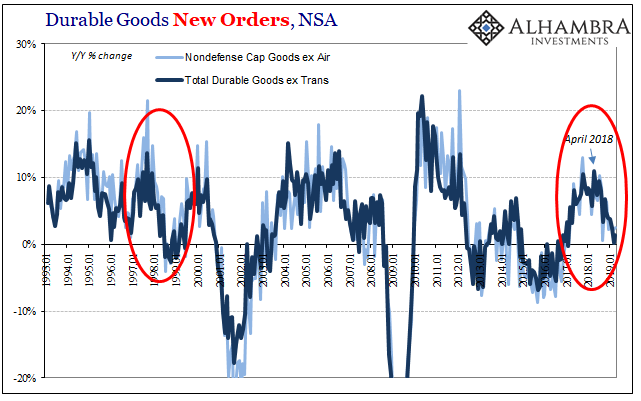

The combination of at best soft economic data like this along with more and more forceful market projections for at least one rate cut, in March Chicago Fed President Charles Evans responded to them by introducing the Asian flu scenario. Overseas turmoil reaching our shores in the manufacturing sector, financial volatility creating enormous uncertainty, all the same kinds of things we find today that happened then.

Two decades ago, in 1998, the Greenspan Fed took what Evans calls the patient approach and then skillfully guided the US economy out of the mess for another two years of Golden Age, New Economy expansion. The “maestro” did so with three rate cuts, and only three. Just enough, as central bank lore tells it, to give the economy a little extra kick to avoid much worse.

If that sounds like wishful thinking, that would be putting it mildly. It’s downright delusional, starting with the idea that the current economy might be anywhere close to what it was in the late nineties. Apart from US stock valuations and the unemployment rate, there is nothing whatsoever comparable.

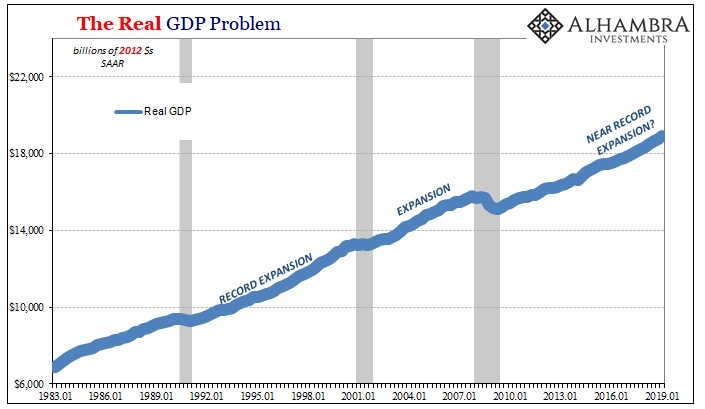

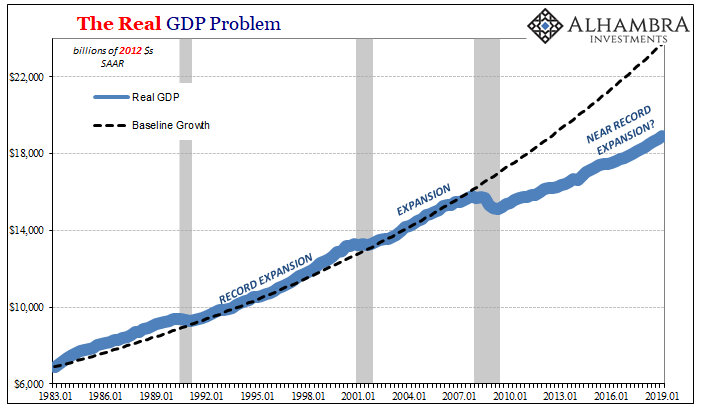

This is, as noted yesterday, the nervous hope of officials who can no longer ignore the curves but cannot help themselves for want of the necessary added perspective. You can envision 1998 maybe in the first chart below, but in no way can it happen in the second – even though they are, in essence, the same exact chart. The only thing changed between them is the perspective, which most in the mainstream including Charles Evans don’t have.

Economic weakness, as durable goods clearly display, is something altogether different when the economy isn’t actually booming. No different than an aircraft beginning a dive from a low altitude, where you start matters, how much time and space you have to pull out of it before the more serious downside consequences.

Not that it would matter when it comes to rate cuts. They don’t actually do much and certainly they don’t accommodate the economy, they only tell the world the most optimistic people possible are no longer optimistic. In that respect, Evans, at least, is pretty much there already. And for that, no serious revisions were required.

Stay In Touch