In May 2018, the European Parliament found that it was incredibly popular. Commissioning what it calls the Eurobarameter survey, the EU’s governing body said that two-thirds of Europeans inside the bloc believed that membership had benefited their own countries. It was the highest showing since 1983.

Voters in May 2019 don’t appear to have agreed with last year’s survey. For the first time since 1979, Social Democrats and Christian Democrats will not hold a majority in that same Parliament. These pro-EU parties have been displaced by a diaspora of the disillusioned. The euroskeptics and outright nationalists scored big, reaching a combined 170 seats in the 751-seat chamber, by far their biggest showing.

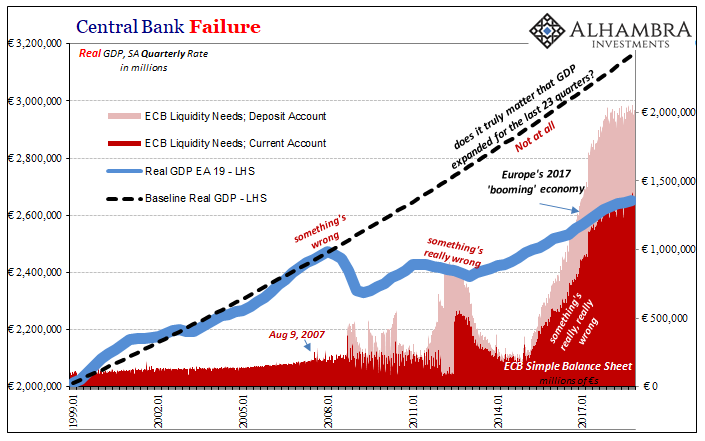

It may not be a total disconnect. Europeans may love the idea of the EU but not its current delivery. In the abstract, things appear popular. In the daily lives of Europe’s citizens, there is absolutely something wrong.

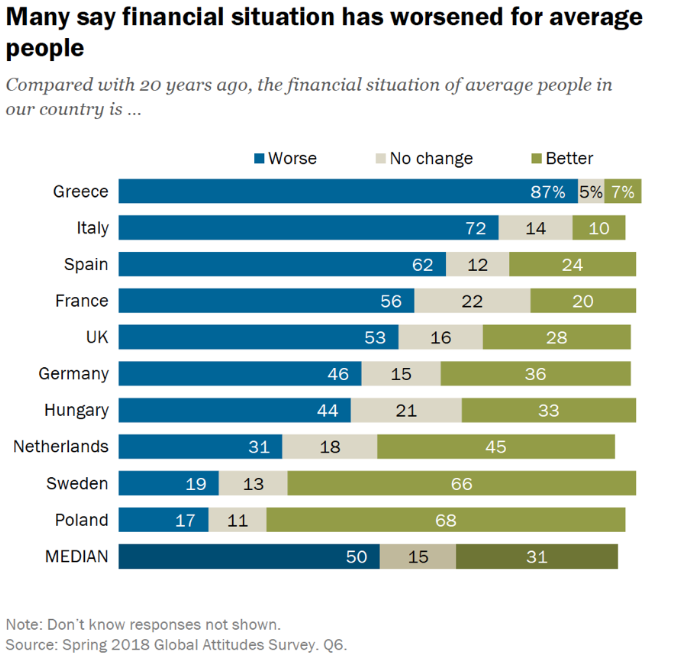

We see this even in opinions on the European economy. According to Pew Research, people believe the EU promotes peace and affluence, only it may not have trickled down to their own perceptions. Fifty-five percent say that the union has promoted prosperity, compared to 39% who say it doesn’t, but in the same survey 62% say the EU does not understand the needs of its citizens.

Again, the disconnect in the abstract. The EU, maybe according to Europeans, is going through a rough patch. It works when it works.

There aren’t consistent surveys through time from which we might compare shifting attitudes – more precisely when attitudes may have shifted. We can reasonably guess, however. The EU was very popular before 2008 in reality as it was as an ideal. Lately, though, attitudes and now voting patterns suggest that the principles of union would be worth supporting if not for the current execution of them.

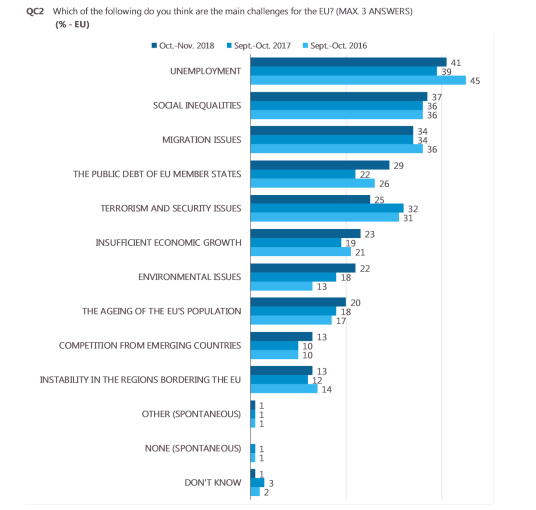

Polling data compiled by the EU (as separate from the European Parliament) shows this is exactly the case. When asked what the main challenges are for the 28-state collective, four in ten answer: unemployment.

That’s down only a few percentage points from 2016, but curiously up from 2017. This was Mario Draghi’s so-called economic boom. And yet, the people within it remain very clearly worried about their own place in Europe’s economy; whether employment opportunities, social inequality (mobility, or lack of it), and immigration (the fear of being displaced).

Small wonder Europe is coming apart. Those in charge, the political class has nothing but the highest grades for their stewardship. You can’t complain about the economic situation because all the central bankers, those who you’ve been told since birth know the most about the economy, say it can’t possibly be any better.

In the absence of honest economic analysis, European’s are making their own choices. They may still hold dear what the EU is meant to represent, it just isn’t anywhere close to enough. No ideal can survive for long being held up strictly as a model. The real world has to be involved somewhere.

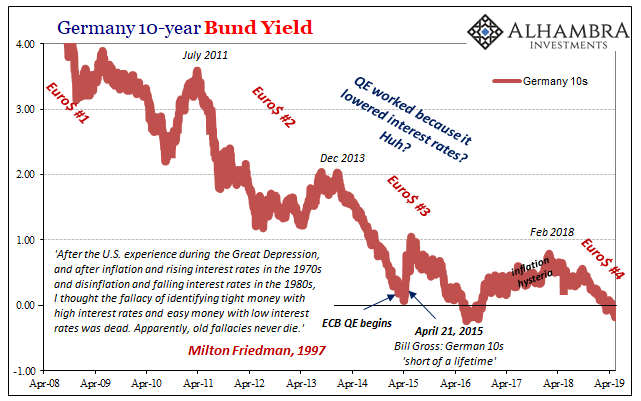

What’s worse, this fracturing of the European polity has all taken place before Euro$ #4. It may not have been a boom, it wasn’t, but it was for a few years better than most. If this is what happens on a modest upswing, what happens when this fourth monetary outbreak really starts to grab hold?

As such, Germany’s unemployment rate rose this month for the first time in five years. The number of German’s seeking unemployment benefits increased by the most since 2009, though officials have claimed the majority of those became eligible through government reclassification. Taking into account the bureaucratic definitions, unemployment in the country would have risen anyway.

Even Economists are starting to get nervous. Stefan Schilbe, HSBC’s chief economist, said, “This reveals that the deterioration of the economy since mid-2018 has started to leave its mark.”

Last week, IHS Markit’s flash PMI (composite) for Germany was just 52.4. The manufacturing index remains well below 50, 44.4 in May just barely above the 44.1 posted in March. Europe’s economic engine is now the key source of its growing weakness.

While all this is happening, as per usual European officials are in a state of complete denial. Mario Draghi keeps saying that the economy has only downshifted from really, really good to merely just good. It will go back to very strong, he claims, once this current soft patch is easily digested. Transitory factors.

At its last organized meeting, the ECB’s Governing Council included this obviously transparent statement:

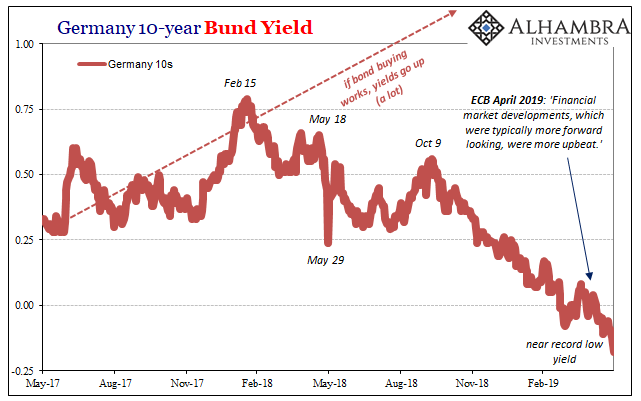

Financial market developments, which were typically more forward looking, were more upbeat.

This is precisely the kind of disingenuousness which fuels the anti-establishment resentment. Stock markets may be up, but they are meaningless in an economic context. In fact, as share prices rise without any economic growth backing them it feeds the inequality argument. Most workers see the economic baseline for what it is and what it has meant in their own lives, and then compare their situations to the DAX and wonder who it is that must be getting rich at their expense.

With German bund yields tumbling back to near record lows recently, it is the perfect dichotomy between reality and ideal. Europeans like the notion of an EU, they’d prefer it didn’t have to resort to outright deceit to keep it going. In the end, as the recent elections have proved, the deception is actually counterproductive. It hasn’t fooled Europe’s citizens into supporting the project anyway, it has instead convinced more and more of them for all that may be good about it the thing just isn’t worth the mounting costs.

Again, that was all before Euro$ #4 really hits home. If it gets like this when things are relatively “good”…

Stay In Touch