You do wonder sometimes whether the person responsible for writing these things ever cringes while they do so. Are they ever shocked by a sudden bout of conscience? Then again, most of it is bland boilerplate language and when it’s not the difference is hidden under a maze of intentionally induced complexity or misdirection.

The statement the FOMC released after its April/May policy meeting started out with the following:

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in March indicates that the labor market remains strong and that economic activity rose at a solid rate. Job gains have been solid, on average, in recent months, and the unemployment rate has remained low. Growth of household spending and business fixed investment slowed in the first quarter.

The labor market remains strong, yet…

The thing is, the labor market is always strong in these statements. Perhaps it is just laziness, copying and pasting the language of the last one to the template for the new one. Why bother to change “strong labor market” when the unemployment rate is even lower.

That’s ultimately the problem here. The unemployment rate drives all these narratives even though there is no corroborating evidence for it anywhere. Not in wage gains and certainly not in terms of incomes.

Job gains have been solid, according to the Establishment Survey, but somehow income gains haven’t. These things are inconsistent. Which is why you find no mention of the latter, only the former. The lack of income would raise serious questions about how the “growth of household spending” had “slowed in the first quarter” and more so whether any such thing could be transitory.

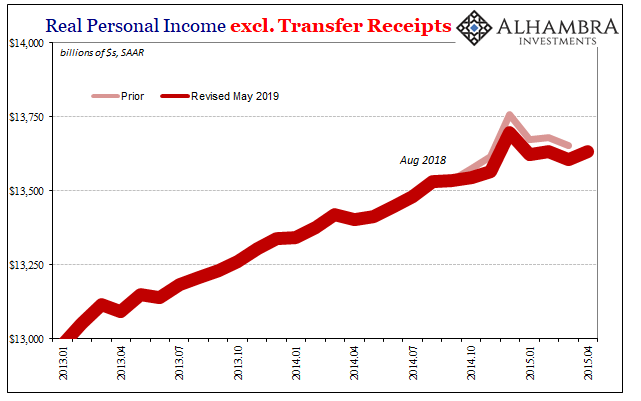

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, they’ve all slowed some more. The BEA revised both incomes and spending downward, more for the former. Shaving about half a percentage point off recent growth rates, that’s only where the problems begin.

As you would expect, if people aren’t actually being hired at the same rate as they had been and they aren’t actually working the same hours and they aren’t actually getting the same raises, incomes would then stagnate or worse. And if that should happen, or even start to happen, most workers respond as rational consumers by becoming cautious at the margins with their discretionary spending (also big ticket things like autos and houses).

Spending would slow by nature. Sure enough:

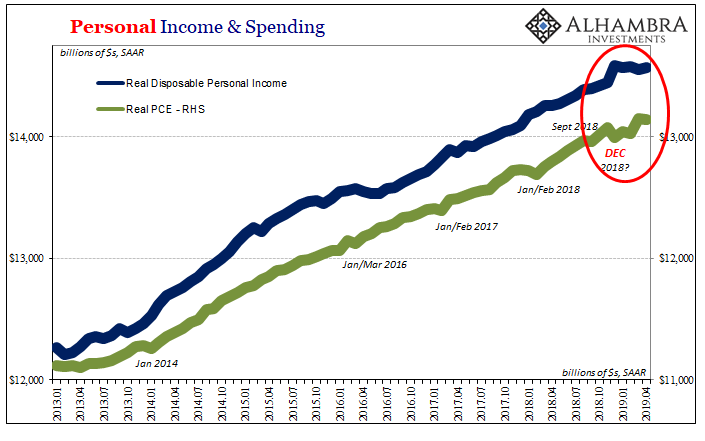

Real PCE spending was slightly lower, seasonally adjusted, in April 2019 compared to March. By itself nothing too much, a very small decline. However, as you can see on the chart above, the PCE series is suddenly quite volatile. Like headline GDP, they really smooth the hell out of it so that this kind of thing doesn’t happen. If it does, then we have to wonder what’s going on here.

This is a noticeable change. A negative month isn’t unusual, but several clustered together really are. The latest estimates (which may be revised in the coming months, perhaps an economist itching to re-smooth the numbers) say that real spending was down in three of the last five, the big one right at Christmas.

It actually goes back to last September, with minus signs (month-over-month) in four of the last eight months. And that volatility perfectly coincides with a lower track for income growth.

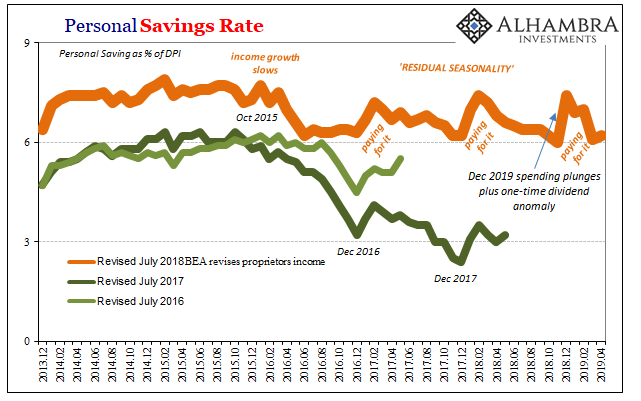

Residual seasonality has been revisited, only this year it began during Christmas rather than immediately afterward in January. In 2019, though, the savings rate was reduced by both lower income growth made still lower by these revisions. So, it’s not normal residual seasonality it just might be something different.

That’s ultimately the point in both income and spending data. Late last year, it more and more appears like something changed – or only started to change – in the US economy. The Fed keeps saying “strong labor market”, pointing only to the unemployment rate while doing so, despite what seems to be strong evidence of a turn or turning process.

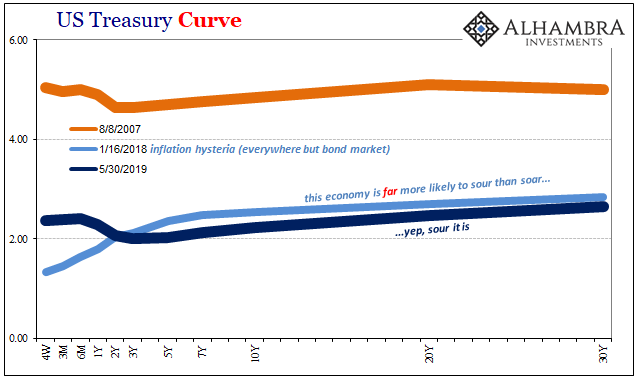

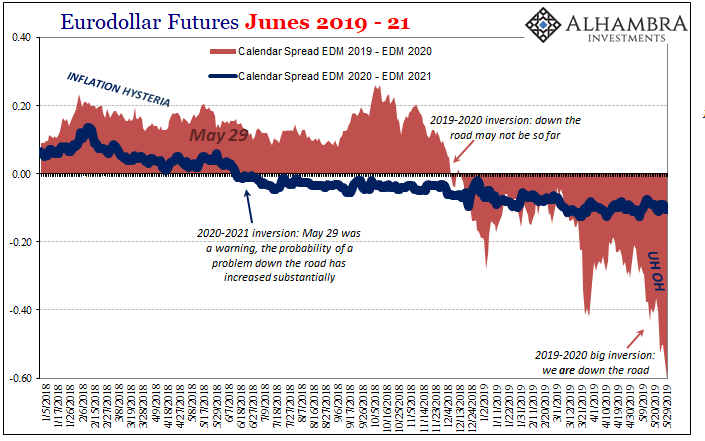

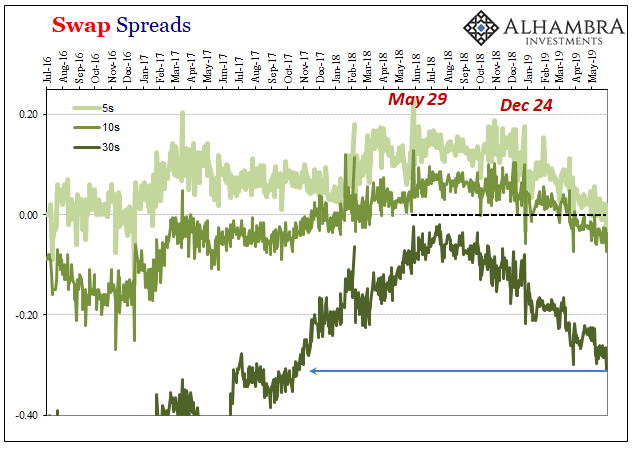

This is, of course, the “bond market” position. From the behavior of curves, it seems rates and eurodollar futures traders got wind of this economic shift around October into November and December.

But that was all mere confirmation of what had been suspected as downside risks going back earlier in the year at least to May 29. Something substantial broke in the global monetary system that day last year, and markets took notice standing on watch as to whether the risks of the global economy catching the dislocation, too, would be confirmed in real data.

More and more, that’s what we keep finding. The bond market position is backed up by a broad cross section of very important economic accounts; income and spending among the biggest pieces of evidence. Not just overseas in places like China, either, but right here in the good ‘ol US of A.

Which tells us, as the market position gets worse, it’s not likely the economic data will turn around soon, either. The idea of a soft patch or green shoots just isn’t consistent with the curves factoring more and closer rate cuts, nor is it consistent with these major data points suggesting an economic inflection already well into the rearview.

The longer incomes keep off-track, meaning labor market weakness, the greater the likelihood a small deviation becomes a big one. Having had negative suspicions confirmed thus far, those are exactly the risks the bond market is signaling right now.

Stay In Touch