I’ve been writing since October when China reopened from that month’s Golden Week holiday that big dollar problems were imminent. You needn’t have taken my word for it, the PBOC said as much. Not directly, of course, but in interpreting the central bank’s anticipated behavior left little doubt.

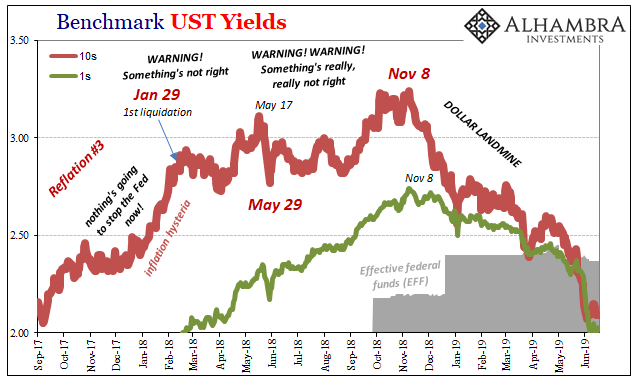

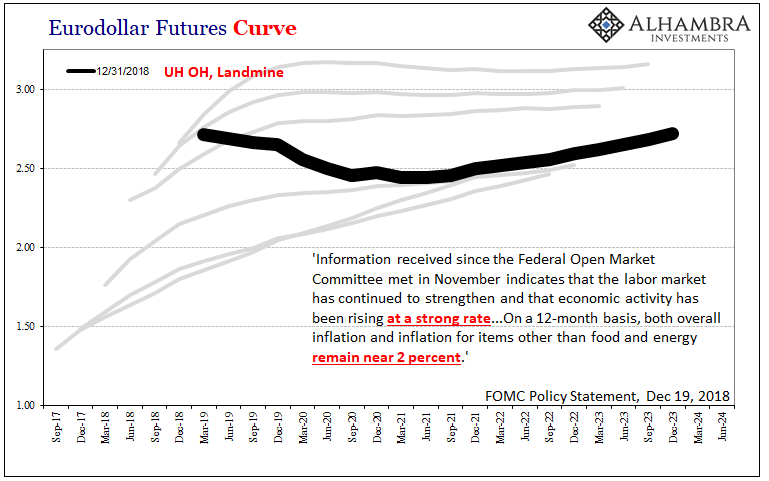

Over the next few months, more and more it seemed as if the entire global economy struck a landmine; the not-decoupled US economy stuck right in the thick of it, too. Recession indications spread especially first in the manufacturing and trade sectors. It has had the effect of masking what’s really going on.

I wrote in the introduction of my recent paper:

The coincident timing of a rise in trade protectionism has formed the basis of many if not most mainstream explanations. In specific terms, the US imposing tariffs on Chinese goods and China’s response to those restrictions only amount to relatively small changes balanced against all of global trade. Attempting to make up the difference, to try and explain very clear and significant downside risks materializing in economies all over the world, economists have been left studying the potential channels of second and third order effects of “trade war” sentiment more broadly.

Rather than seeking to assign uncertainty to intangible concerns about potentially small, non-specific threats, we can look to financial markets for clues as to other alternative factors. In them, uncertainty is equivalent to “flight to safety”, the unusual and significant demand for highly liquid, low risk securities.

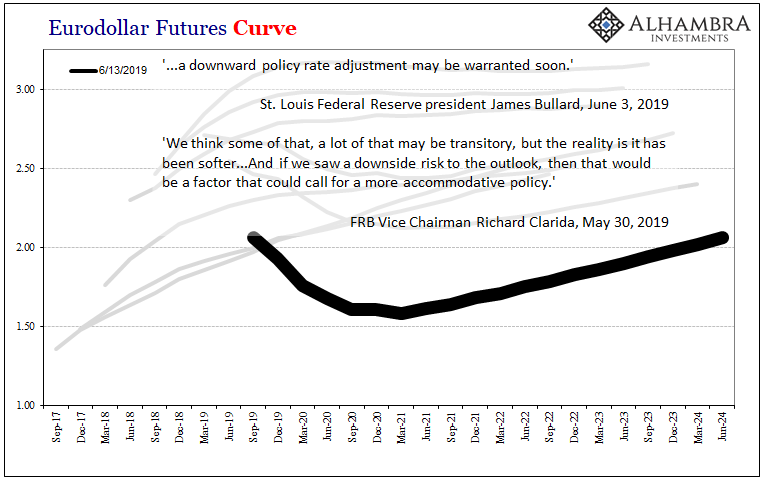

Tariffs aren’t near enough to explain what has happened; not the magnitude of it, anyway. There’s something much bigger, the scale of the October to December landmine declares it of a different origin and nature. Even central bankers being moved unwillingly closer and closer to rate cuts must be wondering what’s really going on here.

Something big happened, alright, and right where we’ve been tracking.

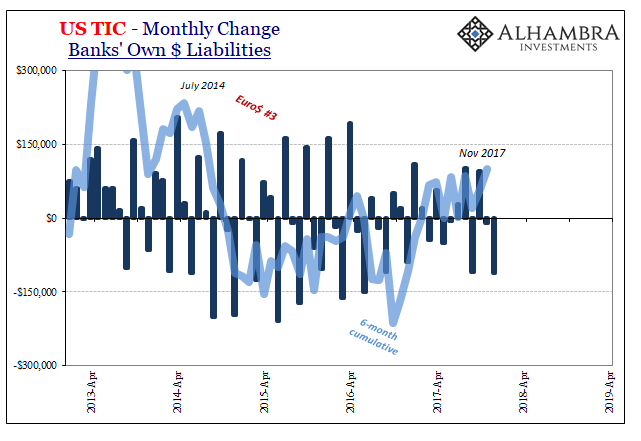

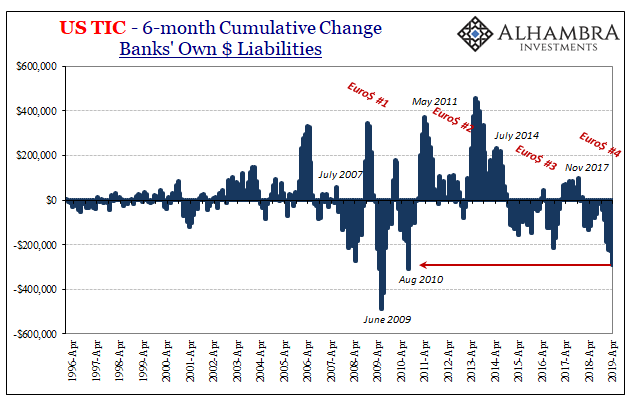

First, a little background and recent history. Using the TIC data for banks’ reported foreign liabilities in dollars, what would take place within any specific quarter was regulatory-driven window dressing. Nothing unusual, this kind of conduct is as old as regulations.

In terms of bank liabilities and TIC, what it had meant was a sort of regular quarterly dance – in the final month of each quarter banks would report significantly less dollar liabilities. In the first month of the quarter immediately following, they would report (to the Treasury Department) substantially higher balances, putting them back so to speak.

The ebbs and flows of eurodollar squeezes and reflations would follow along though keeping to that same pattern; only, lower lows and highs for the squeezes, thus negative in cumulative totals; higher highs and higher lows, therefore overall increases during reflation. Here’s what it looked like up until Nov/Dec 2017:

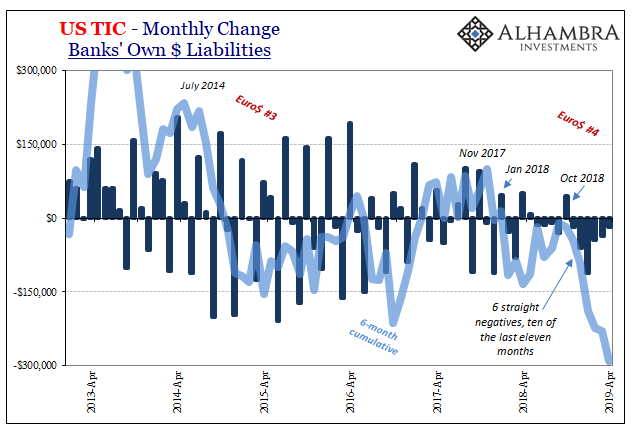

What happened at the end of 2017 wasn’t China tariffs, it was the beginnings of the hard Japan reversal, Tokyo banks fleeing the dollar redistribution business in the wake of China’s Communist government confirming the worse economic case.

January 2018, as noted earlier today in the context of Europe, has proven to be a crucial month in the context of changing economic and financial fortunes. While Japan’s banks suddenly disappeared, the world was struck by liquidity pressures first in liquidations and then in the rising dollar (squeeze) of April and May 2018; culminating in May 29.

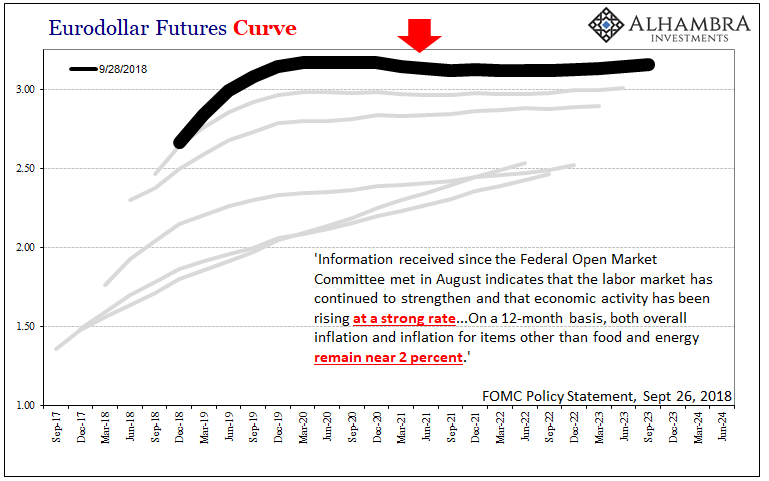

Obviously, by the time we got to May 29 there was much more than just Japanese banks under question. A systemic reverberation which has proven unfortunately durable. Officials, who know and recognize none of this, have been quick to dismiss the signals; it’s all transitory nothing, they say.

Except, we know that can’t be the case by financial markets as well as more and more economic data. The shadow dollar reverberations throughout 2018 turned truly serious somewhere around November:

You can see the change in behavior plainly on the TIC chart above; the quarterly pattern suddenly shifts to a very different one; therefore, whatever happened was over and above the “usual” squeeze. Changing levels is one thing; changing behavior is itself a significant signal. That behavior begins altering after January 2018 but really following, no surprise, the collateral disruption at the end of last May.

From June to September, each of those four months were small negatives (banks cutting back a little more in each one). The last gasp perhaps of any positive reflation followed in October. Beginning in November 2018, however, it’s been nothing but negatives in bank liabilities ever since; six months in a row through the just updated data for April 2019, an obvious and serious change from an established pattern.

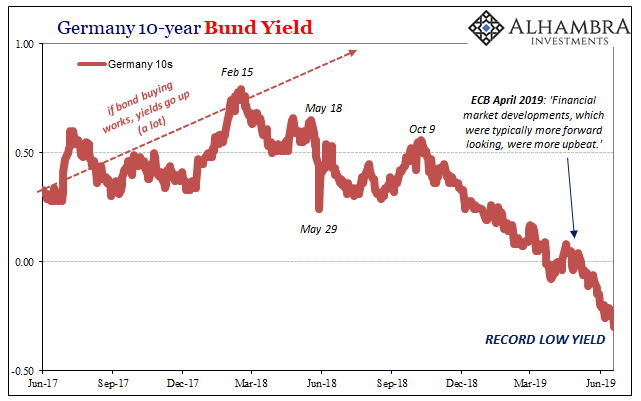

There’s your landmine. During those same months, global bond yields have tumbled as the flight to safety/flight to liquidity speeds into overdrive. Banks are fleeing the offshore dollar markets at a pace not seen since just before QE2 in the middle of 2010.

It adds some pretty compelling evidence as to why this one, Euro$ #4, already “feels” different from Euro$ #3. It has to have been something more substantial still to get banks operating in the offshore dollar space to so thoroughly alter their previously committed pattern.

Under this context, you really don’t want to be able to say, “this time is different.”

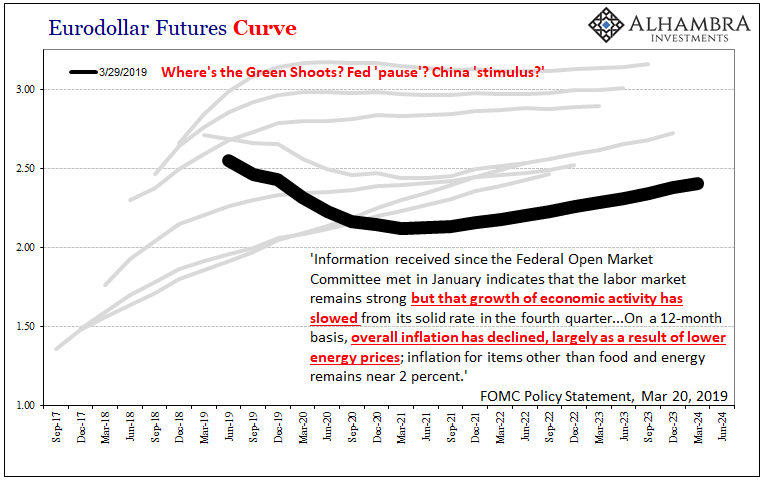

As I wrote yesterday, something doesn’t smell right. There does appear to be a lot more here than simply fears over a simple recession, bad as that might be. It’s as if this building pessimism is being turbocharged and amplified by hidden pressure. You can get to a July rate cut in Europe and the US with serious, quick deterioration in the global economy. But where would that come from?

Europe’s already pretty weak, but the US hasn’t yet displayed as serious of a downshift. In the parlance of Economics, where’s the shock?

What the TIC data tells us, along with bond market behavior (including things like eurodollar futures), is that there is data which backs up our gut sense; the real shock may still be building in the shadows. It hasn’t broken out into the open – yet.

Because of that, it can seem like from the mainstream perspective outside and above the system whoever it is buying bonds and hedging in eurodollar futures is way overdoing the negativity.

The “whoever”, however, is the very same financial institutions who struck that dollar landmine around November. They have more information, even if still far from perfect, than we do – especially in real time. This is why events are following the curves.

There’s a lot of weight in these bond market moves (liquidity risks). The TIC figures, if nothing else, display the seriousness and the stubbornness behind them. It all goes back to the flattening curves of 2017. They said there was little chance of an inflationary recovery before something went wrong.

Something sure seems to have gone wrong, beginning early on in 2018. A final break around May 29 before the real mess starting in and after October. For global banks to rush out of dollar liabilities like this and at the same time pile into sovereign bonds and the like, they’re probably far more worried about something other than the next composite PMI, no matter how subpar.

Stay In Touch