It was a poignant moment that has gone totally unappreciated. Lost in the noise about subprime mortgages, on August 9, 2007, what actually happened that day represented perhaps the best example of how things worked. Or suddenly didn’t.

On the occasion of the 10th anniversary, I recounted the tale of BNP Paribas. You’ve heard of Lehman and Bear Stearns, countless stories about Countrywide and Wachovia. Maybe even something about money market funds. This one French bank’s contributions weren’t really all that remarkable; which is what made it so deadly.

Reuters filed a single report at 2:44am ET on August 9, 2007, detailing the relatively non-specific plans of BNP Paribas to halt NAV calculations for three of its funds. The world hasn’t been the same since.

If the world hasn’t been the same, it’s largely because practically no one grasped the true significance of what BNP was forced to do. Certainly none of our central bankers and officials. It was just too big, too much. To really understand the world post-BNP would mean you had to discard so many sacred truths.

Starting with what I wrote in 2017:

BNP’s MMF’s do more to express the utterly complicated (and often contradictory) nature of the mature eurodollar system in comprehensive fashion than perhaps anything else. These were European money market funds domiciled in France and Liechtenstein sponsored by a French bank invested primarily in US$ ABS to beat euro money market rates. What matters about geography here?

This wasn’t a Wall Street panic as it has been characterized. The Global Financial Crisis was global for a reason, and here at its very beginning BNP showed us that reason. The dollar system may be called a dollar system, we still classify the world’s reserve currency in that way, but that name or denomination leaves out too much that matters.

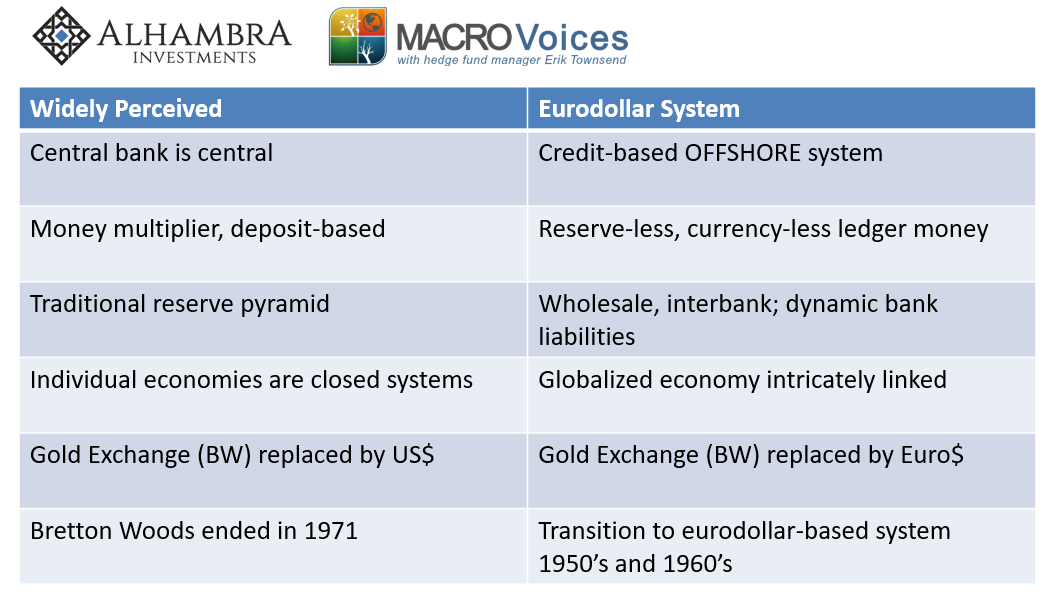

This is why I call it the eurodollar system even though the term eurodollar had a much narrower and more technical meaning many, many years ago. The key part isn’t “dollar”, it is “euro.” That doesn’t specify Europe’s currency, indeed the eurodollar came about decades before the common program.

“Euro” in this context means offshore.

It sounds almost trivial. What’s offshore got to do with anything? On or off, they’re still dollars. Right?

The events early in the morning of August 9, 2007, showed you just what. There aren’t small and separated monetary systems, each clustered around local central banks purposefully centered in the middle of each. The Fed doesn’t sit in the middle of the dollar no matter how many times you’ve been taught this as incontrovertible fact.

The monetary system, the real one that has operated for half a century, is a global money system. The world’s reserve is called dollar but it is actually centered offshore. This is the eurodollar, a complete, utterly complex offshore system and the very one which created the unworkable whirlwind BNP Paribas’ money funds were caught up in.

The world hasn’t been the same since.

One way we know this is repetition. There haven’t been failures like there were in 2008, but that misses the point, too. The focus on individual names fails to appreciate the systemic issues which made them recognizable to every public household. It’s not that we haven’t had another Lehman, or a rash of fund failures like Bear’s and BNP’s, it’s why there were those in the first place.

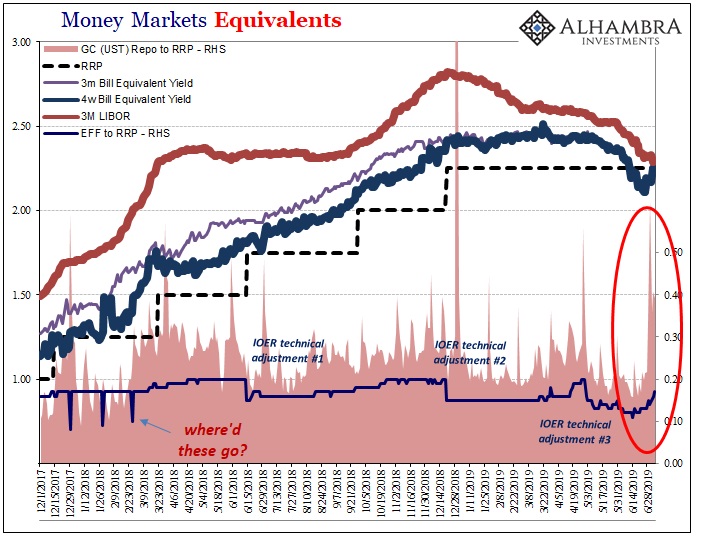

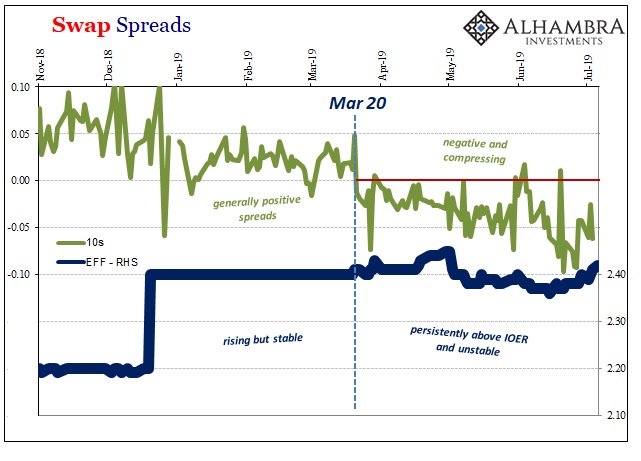

The “why” is what repeats. Two additional completed outbreaks so far with what is absolutely a fourth well under way. In the current systemic monetary shortage, for that’s what these all are, it has finally come home to roost in the Fed’s own backyard.

Federal funds.

We’ve been tracking EFF, the effective federal funds rate, ever since it broke out of its Reflation #3 mold. Through all the dismissals, denials, and, yes, outright lies, EFF has been a key signal that something is very wrong. Not in federal funds specifically, mind you, but out there in the same spaces as BNP found out now almost twelve years in the past.

Thus, we have the answer for federal funds, too. When everything else is exhausted, the sparest of spare liquidity suddenly becomes highly demanded; the last ripples of illiquidity emanating from deeper inside the shadow money world of offshore eurodollars.

Like August 2007, the problem still lies offshore. It connects at various points onshore, federal funds being one. The primary connection is repo. As I wrote in the same piece from which the quote above was taken, it is actually repo which matters a great deal more.

What we observe here, as well as other data, is how the repo market is the last line of liquidity defense in the offshore world. It has become the lender-of-last-resort because the central bank cannot be counted on for what used to be its primary use (raising the question, are central banks, in fact, useless? This isn’t just a rhetorical flourish on my part, it is a legitimate doubt.) This was the major evidence of 2008, reinforced a second time, echoing Bernanke’s bewilderment about transmission, in 2011.

And now because there’s unwanted attention on federal funds, because there’s questions about repo, the Federal Reserve has been made to answer. Nobody in any position of authority over the US system ever wants to talk about federal funds. As I’ve written many times before, it is the one thing that the Federal Reserve is supposed to be able to do without fail, without question.

If the Fed can’t get fed funds right, what can it do?

So, I’ve been alerted multiple times today to a blogpost written yesterday at FRBNY’s Liberty Street Economics. The topic is fed funds and the very complex system behind it. Even the authorities can no longer deny how the monetary system isn’t so straightforward. EFF particularly its relation with IOER no longer allows it.

They even provide an interactive, though ultimately unhelpful, map. The reason I claim this is because the piece saves for the end (as I’m doing here) the only real news worth mentioning. After going through a substantial survey of fed funds, repo, dealers, etc., only near the bottom do they get to the real substance:

Another important piece of the puzzle is the offshore U.S. dollar money market, given the key role that the U.S. dollar plays in global trade and finance. Similar to domestic entities, participants located abroad also own U.S. dollar businesses and need U.S. dollar funding. Therefore, an offshore U.S. dollar money market exists and incorporates, among other participants, foreign banks and foreign branches of U.S. banks.

Do they then outline this offshore dollar market in complex detail as they attempt for the visible domestic system? Nope. It’s another “important piece of the puzzle” but one which is left by FRBNY curiously unexamined. In the whole section, the last one, there are but three paragraphs.

The last one is really the only one which matters from the entire work:

And so to answer our original question, changes in administered rates reach markets where the Fed does not intervene through the web of interconnected relationships between both onshore and offshore participants and through a host of short-term financial products. These interlinkages and connections are the basis for the efficient pass-through of monetary policy.

What they don’t say, what they can’t say, is that these interlinkages and connections can also be the basis for interrupting and overwhelming the pass-through of monetary policy. Exactly what happened in August 2007, as well as what we’ve observed in federal funds since early on in 2018.

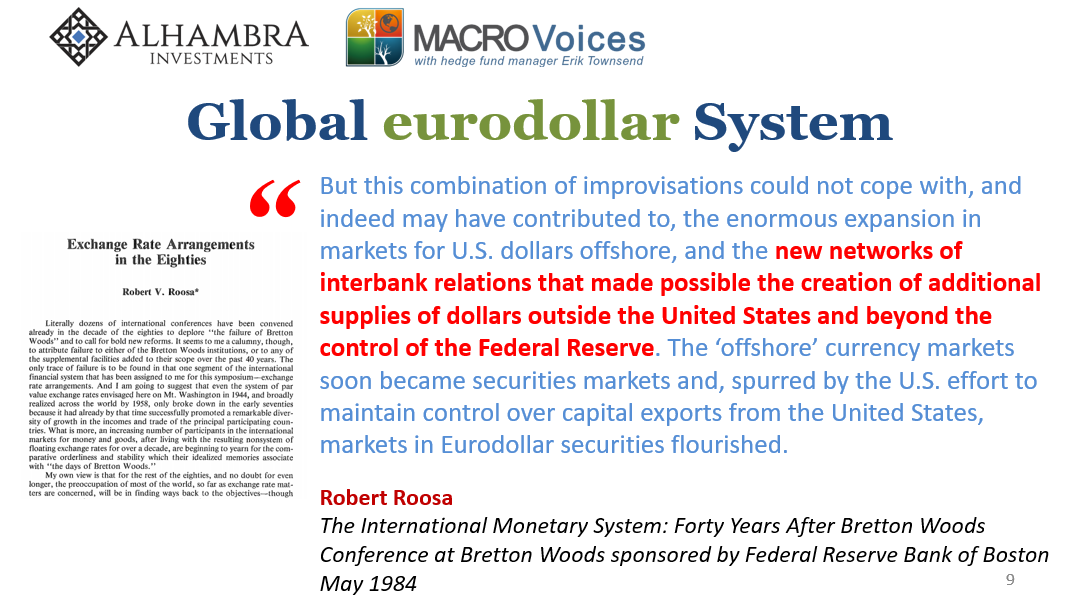

It is amazing, after so much time and after forcing the global economy to suffer unimaginable economic costs, just how close the quoted passage above finally comes to Robert Roosa in 1984.

What we are left wondering is if this represents a positive step or another false dawn? Are the central bankers at least at the branch in New York starting to “get it” finally? If so, what might that mean?

Surprising no one, I’m not that optimistic. For one thing, the evidence is overwhelming and if takes overwhelming evidence plus the passage of a dozen years to finally admit the obvious, and only in the narrow context of fed funds (the complexity behind it), that actually isn’t a very good sign.

And I write that it is obvious knowing full well how it isn’t to the vast majority. The reason for everyone’s troubles, including FRBNY’s, is Economics. You’ve been taught all the wrong things from the very beginning. We all have. But once you set those myths, shorthands, and “incontrovertible truths” aside it all makes a lot of very good, and common, sense.

Even if this does represent a step forward in the slow wheels of bureaucratic intellect, it’s still too late for Euro$ #4. For one thing, as the Liberty Street blog makes plain, after acknowledging the more complicated shadows offshore the authors still don’t think there’s any problem in them. In this case, they are using this belated admission of complexity as a means to downplay the warning signs.

It just doesn’t fit according to their current doctrine of “ample reserves.” That one will be much harder to dislodge (the head fake of QE).

New York central bankers finally come out and admit offshore dollars are important, that they must play some fuzzy role in things, but don’t yet grasp just how important.

Dizzying institutional inertia and ideological rigidity even in the face of so much constant and consistent evidence. There’s still so much ground to cover to catch up monetary officials on effective offshore money even though BNP shocked the world one hundred and forty-three months ago today.

Stay In Touch