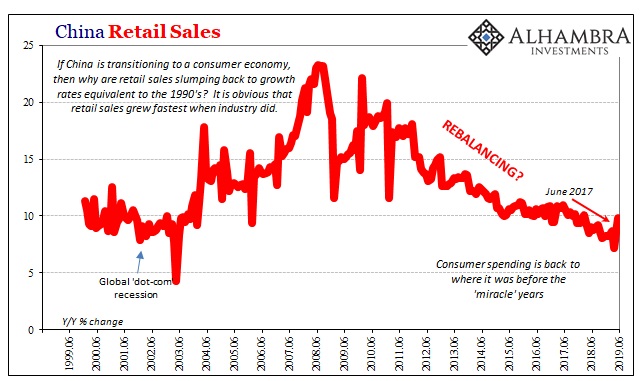

The latest batch of economic from China featured a little something for everyone. For those thinking about a second half rebound, retail sales gained nearly 10% in June. It was the first time near to double digits since March 2018. At the other end of the spectrum, Real GDP rose just 6.2% year-over-year in the second quarter. That’s the lowest in modern China’s history.

The rest of the data fell somewhere in between, a muddled middle of low-state growth and cancelling oscillations. Some are already seeing that as the point, given the obvious context of ongoing “trade war” posturing.

The strong showing of the domestic economy helps bolster Beijing’s argument that growth is robust enough to withstand a prolonged trade war with its top export market.

For the vast majority of the Western media, China’s economy is always some degree of “strong.” Is upside data like June’s retail sales number really necessary? If it is being “managed” as some are implying, it would only be to add a small bit of credence to those ever-charitable descriptions.

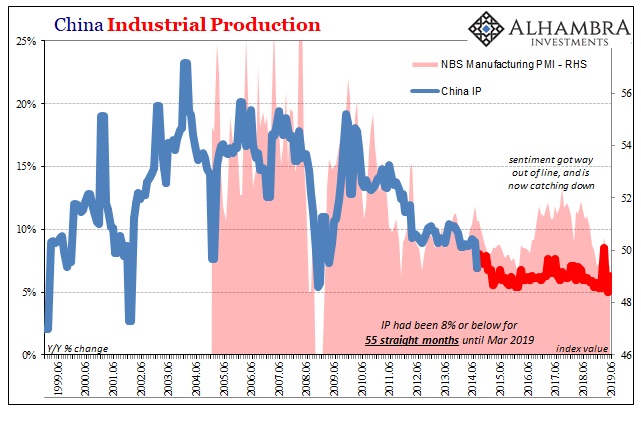

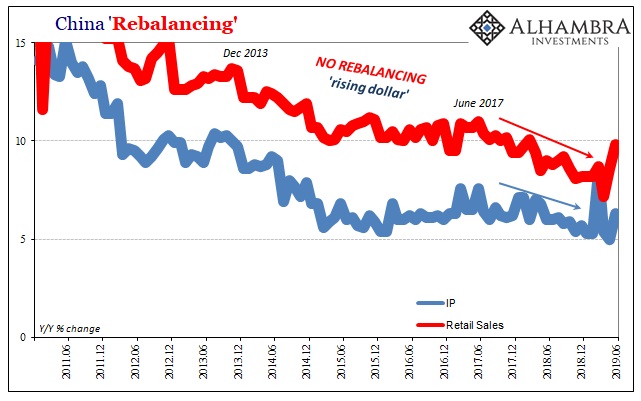

Beginning with retail sales, there’s not yet any reason to believe it’s anything meaningfully different than what we’ve seen before. Industrial Production, for example, spiked in March in much the same way. Coming in above 8% for the first time in almost half a decade, this result was likewise used as a green shoot to predict China’s quick turnaround.

The acceleration quite predictably turned out to be nothing more than an aberration, at most a little more noise in the Chinese numbers than is usual. For the month of June, IP increased 6.3% year-over-year – a better than in May when IP was the lowest on record (outside of a couple long ago Februaries).

That’s where retail sales had been just a month before, in April. Rising just 7% year-over-year in that month, the rate was the second lowest outside of a single month in 2003. There is a tendency to focus on the “strong” economy in the form of these rebounds without factoring the “lowest on record” they are rebounding from.

Month-to-month acceleration is nothing new; the lowest on record, obviously, is.

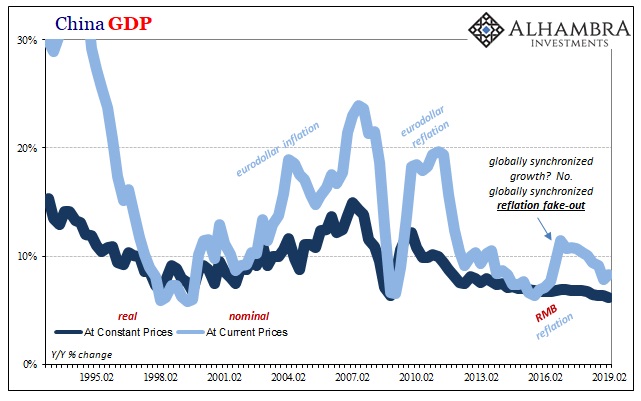

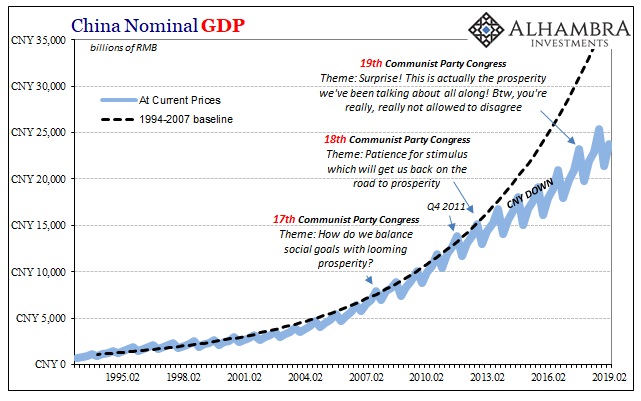

That goes for the GDP numbers, too, though in a quarterly format. While new questions have been raised surrounding the monthly data, there’s always been doubts about Chinese GDP estimates in real terms. Even as Q2 was the worst showing for modern China, that may not mean all that much by itself.

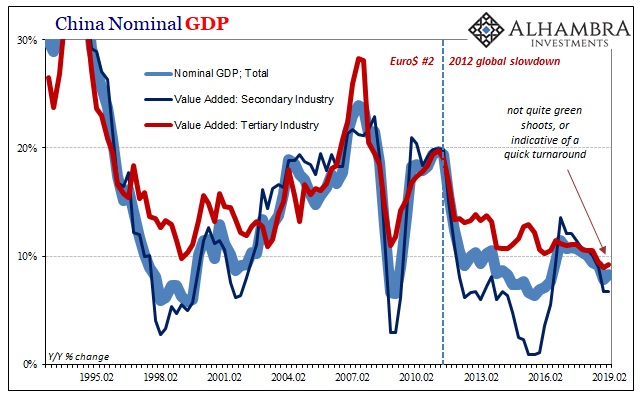

In nominal terms, GDP in current prices, total output increased 8.3% year-over-year during the second quarter (calculated from the reported accumulated increase of 8.1%). That’s slightly better than in Q1 when nominal growth had dropped to 7.8%. While that might seem an improvement, both quarters compare very unfavorably to Q4 2018 when the nominal increase was 9.1% – which had been cause for alarm.

It is nothing more than the ratchet effect. China’s economy slows to a new lower level, it bounces around for a little while in that range, and then ratchets downward again if at irregular intervals.

Inside the GDP numbers you can see what I mean. In what the Chinese classify as secondary industry, meaning actual industry and manufacturing inside China, growth in nominal value-added (GDP terms) peaked way back in Q1 2017 at 13.6%. It slowed to 12.1% in Q2 2017 and stayed almost exactly the same at 12.1% in Q3.

Slowing again in Q4 2017 (11.5%) and Q1 2018 (10.6%), secondary industry “stabilized” in Q2 2018 with a nearly identical repeat of 10.6%.

In Q1 2019, secondary industry grew at a 6.8% rate, the lowest since Q3 2016 and down from 8.9% in Q4 2018. As of the latest figures, during Q2 2019 the growth rate was, surprise, a nearly identical 6.8%.

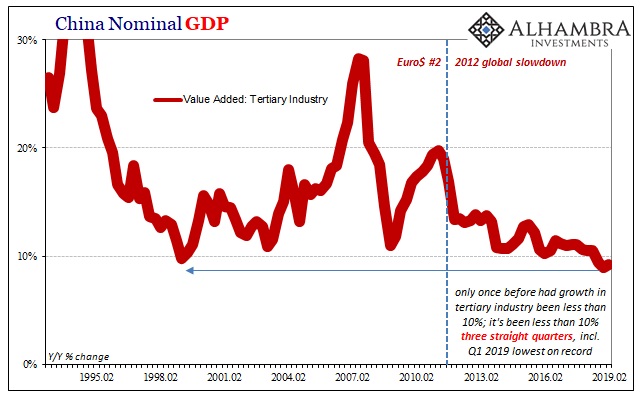

Over in the more important tertiary industries, the service sector key to any concept of “rebalancing”, the ratchet also makes its appearance. In Q2, nominal value-added grew by 9.2% compared to 9.0% in Q1. In Q4, the rate was 9.5% and together those represent three of the four quarters in the entire dataset less than double digits.

Once again, the lowest on record followed by an insignificant rebound. Nothing goes in a straight line, the Chinese economy in particular.

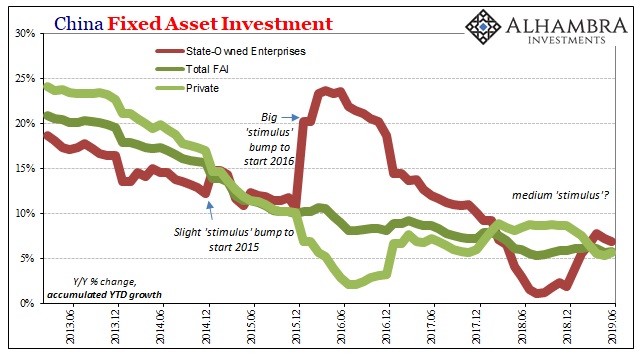

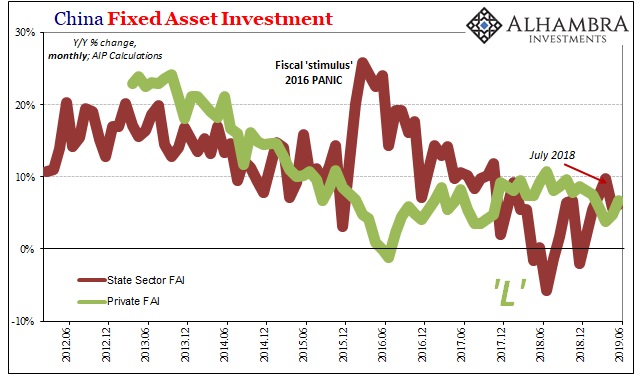

That leaves only some description for Fixed Asset Investment. FAI has been stuck at or around 6% (accumulated) since falling to that low last year. While the overall rate has been maintained more or less in a narrow range, the components within it inevitably exchange places in explaining why that has been the case.

In one period, private FAI activity (the very capex building of modern China) will be accelerating while state-owned FAI (government infrastructure, once related to miracle China’s transformation but what has become more exclusively “stimulus” activity) is all but scrapped. That was last year.

Then toward the end of 2018 private FAI slowed and the government stepped in – but only in a minor way, particularly in contrast to what had happened in the same segment at the start of 2016.

In June 2019, FAI was almost split right down the middle. The accumulated rate in total was 5.8% for all months up to June compared to 5.6% for all months up to May. The slight increase comes as the private side picks up a little from the winter doldrums while state-owned FAI falls back a small amount.

That seems to be the selling point of “managed decline.” At certain times, you can focus on the small acceleration or upside aberrations all the while rationalizing or dismissing the record lows surrounding those points. You can choose to emphasize the “managed” part if you want, and China’s government especially now wouldn’t be unhappy if that’s the way you’ve elected to view it, but even then it still doesn’t remove the “decline” from the process.

With global recession fears rising, even managed decline sounds better than the alternative – a straight out once-and-for-all plunge. Except, we’ve gotten to the point of global recession fears precisely because of China’s (attempted) managed decline. Those concerns aren’t based on the Chinese economy suddenly plunging, they are based on China’s system never meaningfully turning around.

g

g

Stay In Touch