You never fixate on a single employment report. It is a lesson that Jay Powell may not have yet learned. Either that, or he was desperately grasping for straws. The Federal Reserve is trying to thread a very fine needle; on the one hand, the rate cuts. On the other, he doesn’t want them to become a catalyst for people to say, see the economy really is weak!

That means he has to claim the rate cut is a big deal but not that big of a deal because the economy is otherwise strong. Even the FOMC recognizes how business investment and trade are definitely a problem. Consumers, though, they are what will get the economy through these minor cross currents. And that begins in the labor market.

So, according to Powell’s official view so long as the labor market is as gangbusters as ever there’s nothing whatsoever to be worried about. In his prepared remarks for the press conference Wednesday, the Chairman made a point to highlight the last payroll report.

Job growth was strong in June and, looking through month-to-month fluctuations, the data point to continued strength.

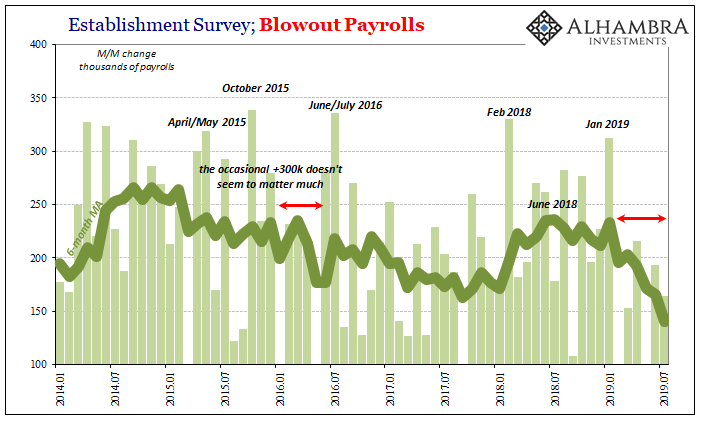

The first part was arguable since anything less than 300k given the current population size isn’t anything like strong. The second part was an outright falsehood, as you’ll see momentarily. That meant Powell was relying on the mainstream interpretation of the one payroll report, June, in order to impute some consistency to the rest of his scandalously suspect statement.

The initial estimate for June’s Establishment Survey released a month ago was a change of +224k. As of today’s updated figures, the payroll change for June has been revised significantly lower and is now just +193k. It is followed by July 2019 and a gain of +164k.

Neither of those numbers by themselves mean all that much. The Fed’s Chairman was right to look through the month-to-month fluctuations, but when you do you are not comforted by what you see in the labor market:

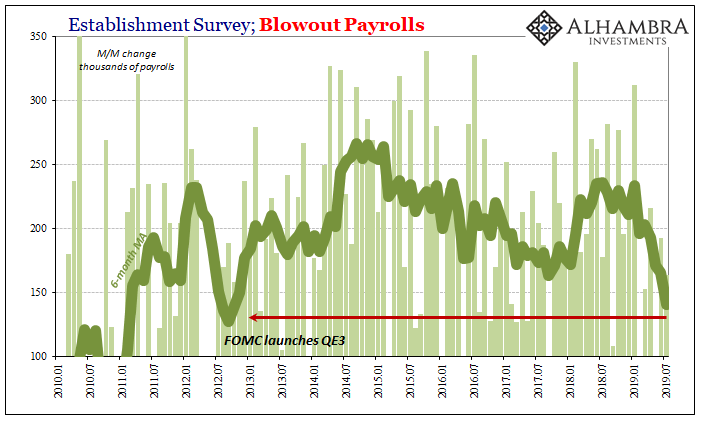

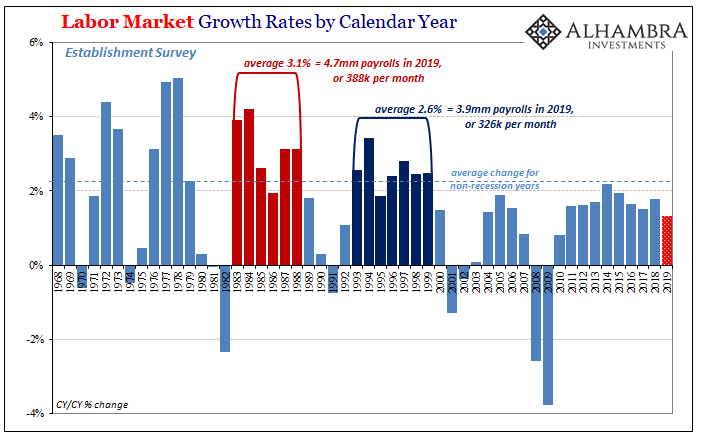

Employment has cooled substantially since January – what can only be the lagged effect of the economy having struck that global eurodollar landmine during the last quarter of last year. In the last six months including July 2019, payroll gains have been above +200k only once, have been less than +75k twice, and are now averaging the least since September of 2012.

In other words, the last time the labor market was in this bad of a shape, Ben Bernanke’s Fed panicked itself into a third round of QE (because they didn’t know what else to do at that point).

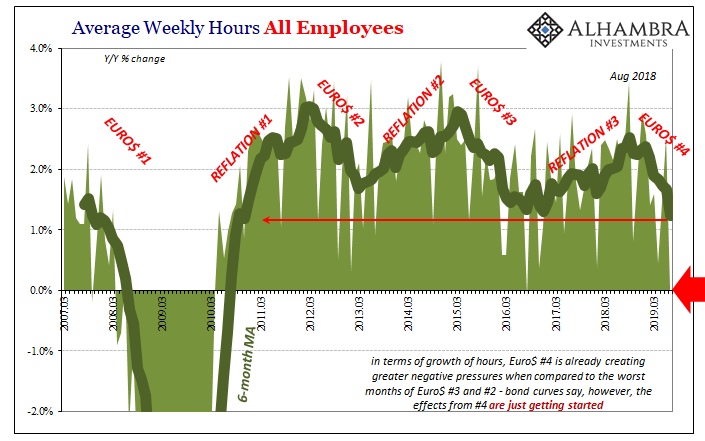

Like 2012, it’s not just the low average that should grab your attention. Look also at the rate of change, the nearing vertical downward slope. As bad as Euro$ #3 was for the labor market, it never went so far so fast the wrong way. The serious harm produced in 2015-16 seems a gentle negative adjustment by comparison.

What we are seeing in the labor market of 2019 may be categorically different. As I’ve been writing, Euro$ #4 is shaping up to be much nastier than either of the two previous outbreaks. Here’s a lot more evidence pointing that way.

Unlike the unemployment rate, there is corroboration all throughout the payroll reports. From a more sober reading of the headline to the underlying details, this labor market projects an economy in trouble. Not just one that is weakening, but one that is already close to the stages of the self-reinforcing downturn.

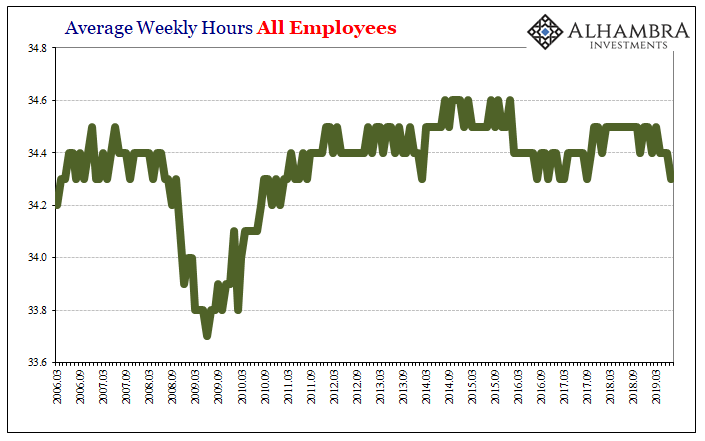

Average hours worked grew exactly 0.0% in July. Again, you never fixate on a single monthly number or even two together. Since July’s nothing came after June’s 2.5% increase, in the short run it might seem hard to tell which one to consider as representative of the true state. The 6-month average, however, shows that like the headline Establishment Survey the labor market has dropped off considerably and considerably fast. The “good” months have become the outliers. These bad months occur more frequently. As a result, the average is the weakest since September 2010.

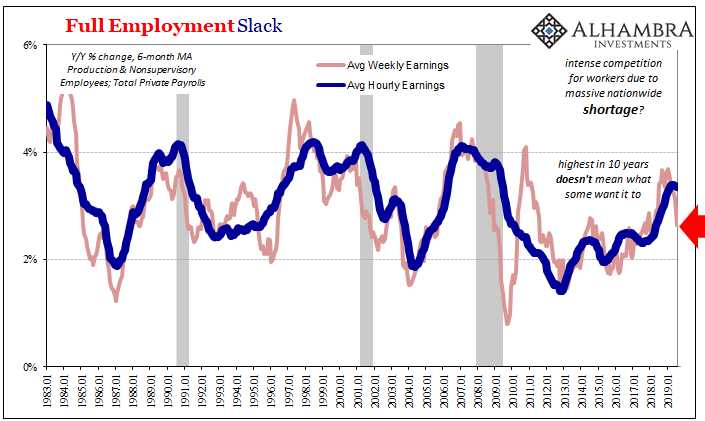

With hours worked decelerating quickly, average pay growth is slowing sharply, too. The increase in the average hourly rate for wages has been drifting lower. Peaking unsurprisingly in December, the rate has inched downward from 3.50% to now 3.30% in the latest estimate.

But because the total aggregate number of hours worked has slowed so much, slower wage growth plus much slower hours means for the individual average worker their weekly paychecks have increased by a much lower rate, too. That’s something that many have probably noticed along with the slower rate of hiring on net (explaining the housing “puzzle” among other things).

The 6-month average for weekly earnings was 3.7% in January, now down to 2.5% in July. Like the Establishment Survey, it’s a sharp turnaround.

Jay Powell has to say the labor market is strong. In that he has no choice. But never should have said look through the month-to-month fluctuations. One has to wonder if he actually did. When you do just that what you find is a whole lot of really serious even alarming changes.

The trend is all that matters. It was never really that good to begin with (above), but now it’s entirely changed direction.

In terms of monetary policy, there’s no way it can be a “one and done” rate cut with these figures. Again, the labor market has deteriorated to the same level and in the same way as what had convinced Ben Bernanke he had better try QE for a third time (and then a fourth). That’s especially true in Powell’s case because he’s staked his whole rate-cuts-are-insurance argument on just labor market strength – which has rapidly disappeared if it was ever there.

Of course, what everyone wants to know is does this payroll, hours, and earnings data indicate recession? It’s too early to tell, but given how the bond market (globally) is being positioned we can say that’s the current fear – the US hasn’t decoupled from what in other places is already bad. I will add that this kind of labor market behavior is a necessary if by itself insufficient condition for one.

Then again, the payroll reports are themselves corroboration for a broad range of data suggesting all the same thing. Euro$ #4 is just getting started and it’s going to be nasty.

Stay In Touch