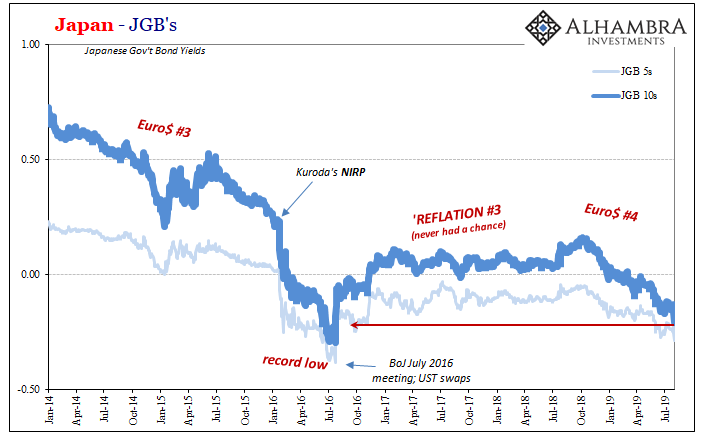

As of today’s close, there are only 22 trading days in the entire history of Japan’s government bonds (JGB) where the yield (or “yield”) on its 10-year paper has been more negative. Those 22 all came clustered together in June and July 2016. In other words, Japan’s bond market is today comparable only to that one period at the utter depths of Euro$ #3.

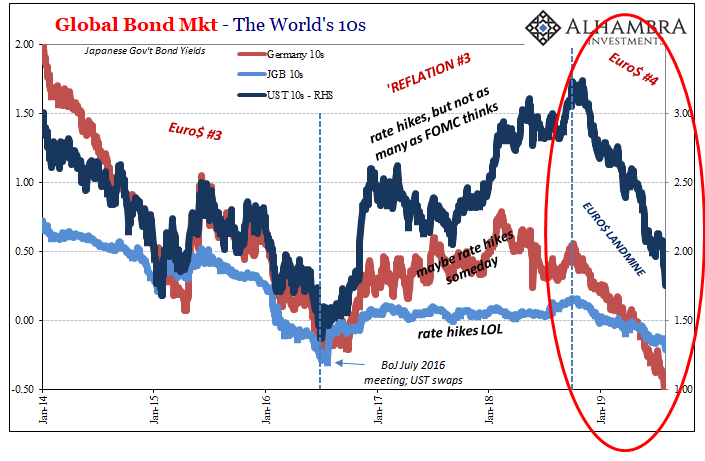

This Euro$ #4 isn’t just a US problem or one for Europe. There is no either/or. It is perfectly clear in showing up across all the majors, as well as the rest of the world. The global bond market is unequivocal; this thing is just getting started and it’s already testing the limits.

In places like Japan and Germany, bonds really didn’t have far to go (neither did UST’s, now only a few dozen bps above their record). That’s not a nod for positivity or optimism; on the contrary, it says that Reflation #3, what the mainstream called globally synchronized growth, was little more than an invented slogan. There really was never much behind it.

In terms of what that might mean for Euro$ #4, it started out from a much weaker and lower level globally than anyone has seriously considered. What is everyone missing?

The Fed has joined a chorus of its peers in cutting rates. More than that, the FOMC abruptly ended QT. This latter factor was supposed to be a really big deal.

We had heard more than a year ago from overseas officials like RBI Governor Urjit Patel (when he was still running things in India, before his country’s economy “unexpectedly” faltered which led to his dismissal after arguing with his government about who really was at fault) who had at least recognized the dollar as a major factor in their building woes.

They just couldn’t figure out why, so they reached for the only things they could see out in the open. This is the problem with shadow money, especially for central bankers who can never admit there is shadow money lest they also admit they aren’t and haven’t been doing the job the whole world had come to expect of them.

Patel had gone so far as to write an oped for publication and worldwide distribution via the Financial Times. He even (correctly) identified how “dollar funding has evaporated” – and this was early June 2018, a week after May 29’s collateral imposition and a week before the eurodollar curve would invert for the first time. Good for you, Dr. Patel.

But then he said it was all due to the Fed’s unwinding of its balance sheet at a time when the US government deficit was sharply rising. This was, Patel called it, India and the world’s “double whammy.” Double dollar whammy.

The second part made some sense in the context of the middle of 2018. Some. UST yields back then were still in a slight rising trend though that trend had been rudely punctured by the contradiction of May 29.

People had been arguing, and some still are, that Primary Dealers were being stuck with T-bills. The federal government because of December 2017’s tax reform has been running huge fiscal deficits again. Financing them has required a sustained avalanche (or deluge, as some prefer) of bills to be issued and auctioned, which the Primary Dealers are obliged to buy.

The dealers then have to fund what they are stuck holding particularly if they can’t find any outside buyers. This (supposedly) explained the repo market and by extension the growing wackiness in federal funds. When rates and yields were rising, it sounded plausible.

How about now, though?

If Primary Dealers are right now having trouble selling off excess UST inventory, bonds, notes, or bills, then they should have every single dealer privilege revoked. As I wrote last week:

To believe in this convoluted theory, you are asked to believe that primary dealers whose entire job is to find buyers for Treasuries are disrupting repo markets and other funding mechanisms because they can’t find enough buyers for Treasuries during a time when there is otherwise so much demand for Treasuries it has upended the natural order of curves everywhere…

Yields [have] plunged. It seems there is still an overwhelming desire coming from somewhere (everywhere?) to buy up UST of all kinds, up and down the curve. If dealers truly are having trouble selling Treasuries they should probably be put out of business for being so inept at the task.

In other words, that’s one whammy (thoroughly) debunked.

As to the other: if QT was such a huge problem, then why has the global bond market reacted very differently to its termination? If either whammy had been real whammies, then yields would’ve skyrocketed in renewed happy reflation. The world of growth and normalization is one with much, much higher interest rates. We will all truly celebrate the bond market’s devastating demise.

Instead, rates all over the world have sunk closer and closer to record low levels (with Germany importantly having already surpassed them). This isn’t stimulus, as orthodox theory posits. It is big, big trouble.

The bond market is saying the landmine is what’s been real. And saying it in unison.

You can and really should interpret the end of balance sheet normalization as consistent with what motivated Patel in the first place.

The reality of the situation actually and unintentionally may be best explained by the abrupt end to QT. The FOMC won’t say it publicly, but it’s not what they say that matters, pay attention to what they do. They’ve decided the system really might need a whole lot more reserves than they ever had planned for. In Jay Powell’s thinking, maybe there is something wrong that more reserves might fix.

Another way of saying that?

The world really does seem to be short of dollars.

You better believe it. The bond market sure does. And it also knows it had and has nothing whatsoever to do with either T-bills or QT. The global financial system is scarce of dollars, and excuses.

Now, if only the US and China could get a trade deal done.

Stay In Touch