It was truly startling when it was announced. The second and more dangerous phase of the Global Financial Crisis had begun on July 15, 2008. Within two weeks, Merrill Lynch had etched its name on the growing list of “troubled” institutions.

On July 28, 2008, Merrill Lynch agreed to sell $30.6 billion gross notional amount of U.S. super senior ABS CDOs to an affiliate of Lone Star Funds for a purchase price of $6.7 billion. At the end of the second quarter of 2008, these CDOs were carried at $11.1 billion, and in connection with this sale Merrill Lynch will record a write-down of $4.4 billion pre-tax in the third quarter of 2008.

There are all sorts of misconceptions about the sale, some that have continued to this day (for the few who notice these kinds of things). What immediately jumped out was the $6.7 billion purchase price for what seemed to have been almost $31 billion in assets. Indeed, the vast majority of the news stories (many of which have disappeared over the years) written at the time described Lone Star Funds’ incredible deal of 22 cents on the dollar.

Everyone knew it was “toxic waste” and damn if Merrill wasn’t loaded up on it. How much is everyone else really exposed?

All the press release said was “$30.6 billion gross notional” not par value nor book value. We don’t know, and none of Merrill’s previous filings had ever specified, what the market value of these assets had been at inception. “We don’t know” is how a lot of these things worked.

This highly uncertain nature raises some very good questions along the lines of monetary mechanics. Shadow money. The kinds of lessons that stick with you long after the affair has been put to rest in the history books.

Merrill’s CDO sale in some ways reinforced the example of Bear Stearns – and not just because a lot of Bear Stearns’ troubles were related to its own holdings of ABS CDOs.

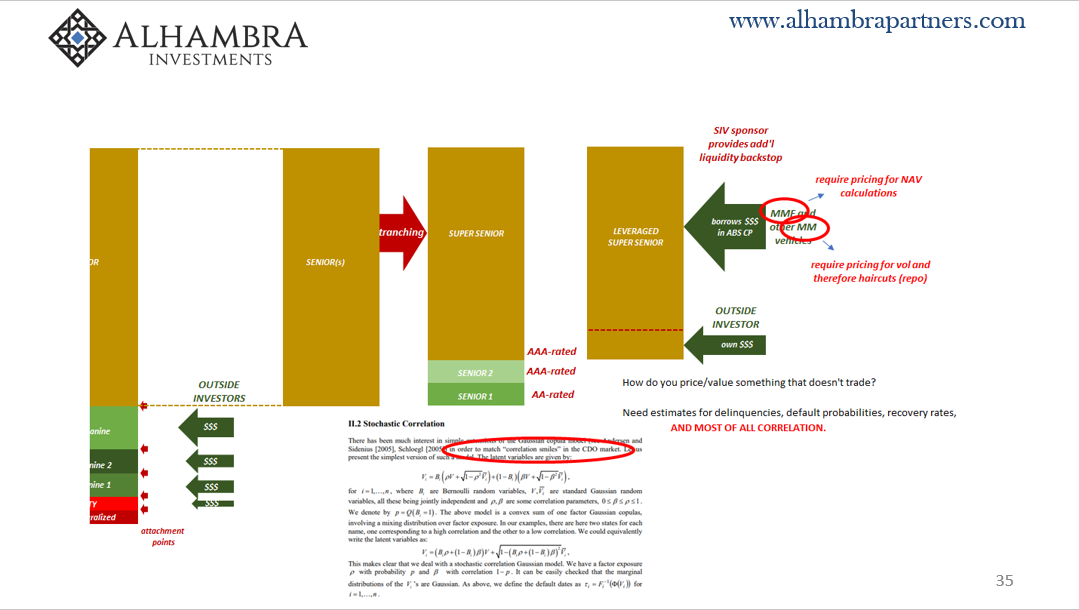

We can spend an awful lot of time diagramming and detailing these instruments and those like them, what they were used for and why banks seemed so enamored with the type. In fact, I’ve already done so elsewhere (Eurodollar University). ABS CDO’s can be of a couple different kinds but what they all have in common is that they make what is erstwhile illiquid assets into a liquid security.

What’s so important about that? In a word: repo.

You can’t show up at JP Morgan’s repo desk with a lot of papers holding title to thousands of mortgages and expect to fund them on the basis of those individual loans. That doesn’t work. For one, the cash owner, the interbank repo lender, wants collateral that is highly liquid because that way the cash owner knows the collateral being received isn’t going to move much while in his possession.

If you default by refusing to return his cash and he’s stuck with all those individual mortgages, what good are they for his purposes? He can’t liquidate them tomorrow and get his money back.

Pool them together in a securitized structure, however, and now you’ve got something. In fact, you can pool many different types of assets and securitize them (the term is taken literally). Pools of plain mortgages; pools of subprime mortgages; pools of tranched pieces of pools of mortgages, or pools of pools (CDO-squared). What comes out in the end is a security which if it has a market then it becomes repo gold.

So much of Wall Street’s efforts during the housing bubble were focused on making markets, or market-based inputs, to price these things (the real story behind the Big Short).

Should their tradeable characteristics remain inside acceptable limits and tolerances, even private-label subprime toxic waste was acceptable as “pristine” repo collateral. The whole system seemed perfect, reasonable and, yes, safe. The funding was cheap and the profits fattened on both sides – riskier assets meaning higher rates of return plus lower funding costs as the best of both worlds.

And the repo cash owner was protected by collateral that could be liquidated on demand in a predictable manner.

But once people started asking questions about it, wondering if there was actually “toxic waste” out there, the repo characteristics were shot. In the highly leveraged, low tolerance system which had built up throughout the nineties and middle 2000’s on the assumptions of systemically low risks, there was no room for adjustment.

What many people don’t get is why the bank doesn’t just sell the thing. Once it is rejected by the repo market (haircuts raised too high) and becomes too difficult to fund, why not just dump the asset and be done with it?

Merrill Lynch in July 2008 provides our answer as a worst test case. If your repo funding begins with an asset like this, it starts out with prices and therefore repo characteristics (haircuts) based on liquid trading. But in the case of a lot of mortgage-related structures in 2007 and 2008, that liquid pricing just disappeared.

Not only does that mean your repo counterparty (the cash owner) is demanding a much greater haircut, you can’t just sell the asset because if you do sell into an illiquid market you take an enormous loss which might confirm to the rest of the world that you really are a troubled bank. It may not have been 22 cents on the dollar for Merrill in July 2008, but those ABS CDO’s produced billions upon billions of impairment losses (and another $4.4 billion which were booked in Q3 2008 after the sale).

That’s the real risk of illiquid assets being used in liquidity functions. At some point, they can just return to type.

That leads to questions being asked in the other direction; why didn’t Merrill just come up with additional repo equity to keep funding the positions?

These were super senior tranches which means there were almost no credit losses in them (which is what Lone Star was betting). As hard as it is for people to accept in the aftermath of 2008, securitizations had performed just as they were designed; the seniors and super seniors never booked cash losses, only price impairments due to illiquid market conditions. Even the most toxic of toxic waste would wipe out only the lower tranches; the embedded credit protections (thickness) had worked.

You have an otherwise money-good asset being priced all over the place if at all – and because of that it is no longer repo-able collateral. If you do dump it, you can only sell it to a vulture fund type for (dimes, more likely) pennies on the dollar, being made to book huge losses that will only make your situation worse.

If only you had enough pristine collateral sitting idle on your balance sheet where you could substitute that unassailable security in repo and therefore maintain the funding you need in order to bury that illiquid monster somewhere on the balance sheet until the storm passes – and its value goes back to up to reflect a more reasonable and fundamental level. That substitution ability buys you the most valuable thing in a crisis – time.

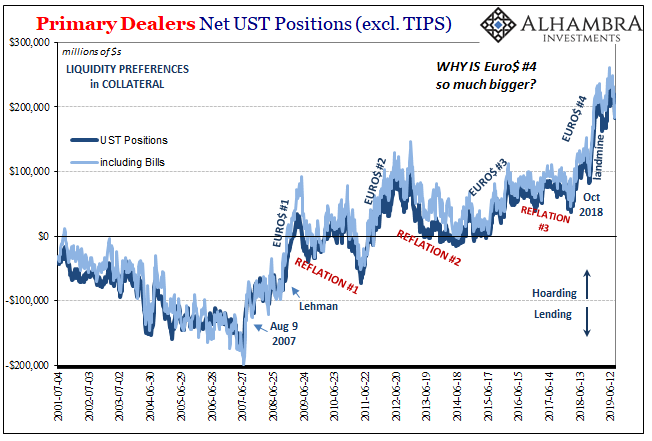

By selling the CDO’s in July 2008, Merrill was basically admitting it didn’t have enough spare collateral on hand in inventory to perform this repo substitution. The firm didn’t have enough UST’s. And because the firm wasn’t sufficiently stocked with “spare” UST’s, the company was made to suffer a highly troubling public sale at the worst possible time.

One of the oldest and biggest names on Wall Street ended up being “sold” to Bank of America not even two months later if only to avoid another Lehman.

What lesson might all of the global banking system have learned here? Simple. You better have some UST’s lying around on your balance sheet, a lot of them potentially, in case things turn in illiquid markets again. You can’t risk being caught without what are, essentially, repo reserves. Not bank reserves but collateral reserves.

That’s what UST’s are, or German bunds overseas in Europe; they are balance sheet tools and it truly doesn’t matter what their return might be. The credit characteristics of the US government don’t make a bit of difference. You hold them in inventory because of only their liquidity characteristics.

If the yield happens to be record low or negative, that just means the costs of repo reserves are that much higher (and what does that tell us about the demand for them?)

Banks still do risky things with otherwise illiquid assets like what used to be in ABS CDO’s because they have to do risky things – that’s what banks are supposed to do. They don’t do them to nearly the same levels of stupidity as the old “toxic waste”, but there’s always going to be some stupidity because there’s no getting around the basic nature of the system.

What’s changed in addition to the lower level of stupidity is how quickly the system responds to these perceived threats. Nowadays, it’s not subprime mortgages that is on everyone’s mind, it is more likely junk bond CLO’s, leveraged loans and the like (especially Eurobond CLO’s). And the Merrill’s of the world in 2019 might only be exposed to the CLO’s in some sort of collateral transformation regime.

Still, at the first small sign that the junk bond or leveraged loan or CLO market might turn illiquid, it makes perfect sense that banks (in the generic global sense) would go running for UST’s and German bunds. Build up that spare liquidity margin, build up those repo reserves in case the illiquid market for CLO’s or other similar assets really starts to turn ugly.

You never want to get stuck (again) having to sell increasingly illiquid assets because you can’t use them in repo. If you have spare UST’s, if you’ve built up these repo reserves of pristine collateral, you’ve written for yourself a liquidity insurance policy because you’ll be able to easily (relatively) substitute them for the troubled asset.

The more you might sense that illiquid markets might become a problem (again), the more you are going to add to your stockpile – even if the US government is the brokest entity in human history (and it is). The illiquid market conditions matter tomorrow; the credit risks of UST’s, as the Japanese have shown, won’t matter until a long way down the road, if ever.

What we don’t know is the real level of stupidity ten years later; that hasn’t yet been revealed. It may not be as great as it was with subprime mortgages and ABS CDO’s, but that doesn’t mean it’s a cakewalk. You might guess by the behavior of global sovereign bond yields that those firms subject to these conditions and arrangements as I’ve described them are taking the liquidity risks of some unknown level of stupidity very, very seriously.

Negative and record low yields make sense for reasons that have nothing to do with investments in negative and record low yields. You have to see these assets as balance sheet tools, repo reserves whose entire purpose is to allow a firm to weather a market storm which disrupts the normal characteristics of how the world truly operates. The cost of holding those reserves is immaterial to the survival characteristics which are contained within them.

For as much as every central banker dismisses liquidity risks because of QE and bank reserves, none of them, not a single one, says anything about repo and collateral reserves. We don’t need them to say anything – the bond market is speaking for them.

The FOMC used the term “strong worldwide demand for safe assets” last year without really knowing why. All the way back in July 2008, Merrill Lynch had shown everyone why, but Economists and central bankers just don’t understand bonds.

Stay In Touch