Before the repo rumble this week, Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell wanted to coast into a second rate cut on the comforting breeze of his insurance rhetoric. No longer one and done, that’s done, a second straight cut would be more consistent with a more forceful yet unnecessary policy response. Again, his publicly stated view is that the US needs rate cuts even though it doesn’t need them.

Losing control of fed funds simply wasn’t in the plan. It’s hard to argue there’s no need for “accommodation” when it’s on every front page. So, Powell addressed these burdens by embracing yet another easily disproven canard. That way, he still gives out the planned second rate cut while maintaining how it wasn’t really necessary.

Asked about fed funds and repo at his press conference, Powell was unusually, suspiciously clear about these funding pressures:

They have no implications for the economy or the stance of monetary policy.

The story gaining traction in the mainstream is that the combination of dealer space (lack of) and a tax-receipt related drawdown at Treasury has left the funding markets uniquely exposed. In other words, “technical factors” that were, dare I write, transitory in nature. The Fed’s overnight repo operations, therefore, nothing more than a short-term response to a non-issue in the bigger picture.

That’s the story they’re going with.

I think what really bothers me the most about all this is the constant denial. This mess didn't just show up yesterday. They've been saying no big deal since EARLY 2018. And now it's a big deal because…technical factors? They already used that excuse last August.

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) September 18, 2019

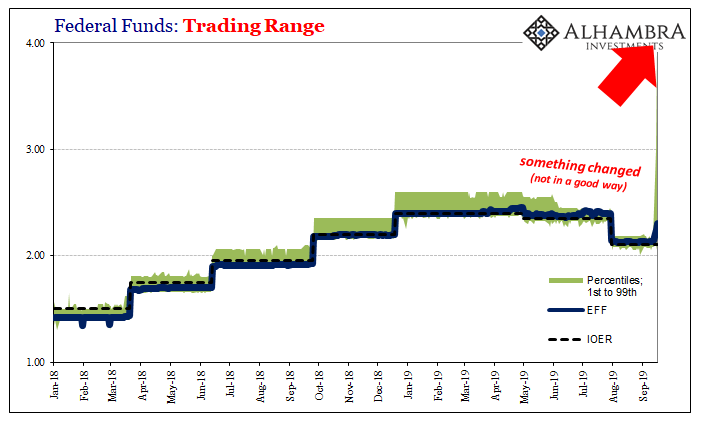

I doubt he actually believes any of it. For one thing, Powell has been battling fed funds ever since he arrived in office. Go all the way back to early 2018, there’s been one issue after another with fed funds. This isn’t something that just snuck up on everyone out of the blue, it’s been working in this one direction for more than a year and a half already. And in that time it’s just coincidence, random back luck how they’ve gone from rate hikes, big inflationary boom to rate cuts and questionable “global” growth?

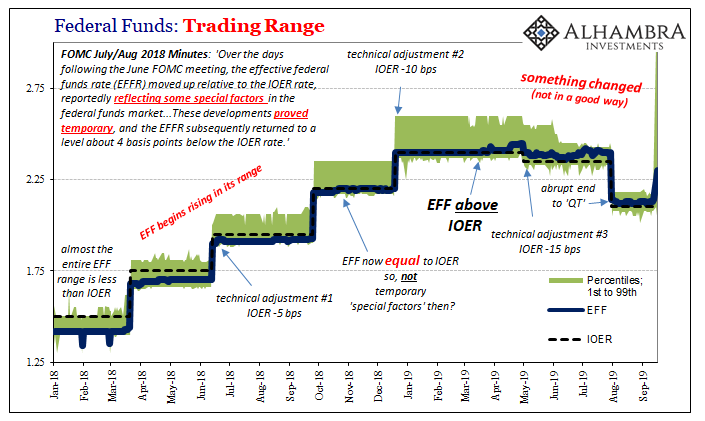

If this is about one-off technical factors, then it has been a highly unusual series of them. Recall what the FOMC wrote about fed funds a little over a year ago, at the July-August 2018 FOMC meeting (statement taken from the published minutes of that meeting):

Over the days following the June FOMC meeting, the effective federal funds rate (EFFR) moved up relative to the IOER rate, reportedly reflecting some special factors in the federal funds market, including increased demand for overnight funding by banks in connection with liquidity regulations and a pullback by Federal Home Loan Banks in their lending in the federal funds market. These developments proved temporary, and the EFFR subsequently returned to a level about 4 basis points below the IOER rate. [emphasis added]

Special factors. Temporary. June 2018.

And yesterday EFF (forget their R) registered 20 bps above IOER while the top end of the fed funds range reached 400 bps. In other words, if the issue in fed funds really had been FHLB’s and liquidity regulations (oh boy, 2a7) then why is it that EFF and IOER have continued to relentlessly progress the wrong way?

Last year’s temporary special factors must have been replaced by another set of them (anyone remember the repo rate on December 31, 2018?) and then another and another and another. At some point, you have to realize there’s nothing special about special factors because if they keep repeating that’s just the baseline.

It’s transmission – in this case, growing systemic problems.

But Powell cannot under any circumstances ever say that. First rule of central banking is not to make a bad situation worse. If policymakers are concerned about repo and fed funds, unsure really what to make of the situation, then the central bank manual says play it cool. Give the system a little bump, but downplay any need for it.

Have your rate cut and eat it too.

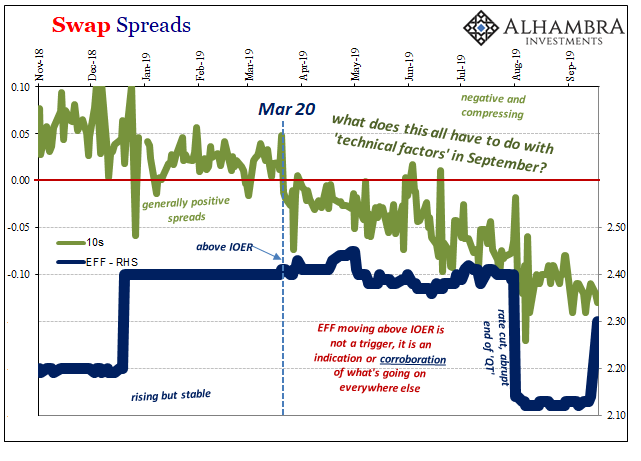

Powell and the FOMC are right about one thing; what’s happening in repo isn’t the end of the world. It’s not good, but it doesn’t suggest 2008, either. This isn’t the system violently and quickly breaking down, a pure, raw burst of emotion and unbridled fear. That’s not what we see in money markets.

It is still disorderly, to be sure, and that’s pretty bad, but what’s going on instead is a regular calendar bottleneck that everyone knows is there further exposing these same systemic flaws in capacity – what’s been building ever since Reflation #3 turned into Euro$ #4 early on in 2018.

Given the specious correlations put on display here, someone should ask if Powell or anyone on the Committee has considered that he might be the cause of all this since it just so happens to line up better with him taking over from Janet Yellen than any of these other “factors.” Powell starts in February 2018, EFF starts to rise in the range. It’s a much more credible assertion than what’s being passed around.

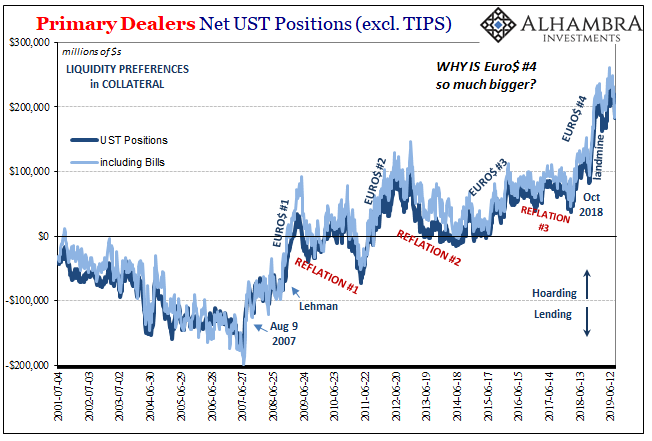

The real canard in all of this remains UST’s. That guy at Credit Suisse has said dealers are statutorily obligated to buy them at auction, and since the reckless federal government is auctioning more and more (which is true) they are being stuck holding the bag. Given that UST’s in dealer inventories are funded in repo, allegedly this explains repo and therefore fed funds, too.

Complete and utter crap. Anyone circulating this story is expecting that you don’t think too deeply about it or maybe how you aren’t able to employ basic common sense.

Dealers are, actually, required to buy UST’s at auction. That much is true. There is no law or statute that says they must hold on to them, however. A dealer’s entire business is, in fact, to buy at auction and then sell to the financial public.

Therefore, to get to being “stuck” holding UST’s you have to then imagine a lack of demand for those very securities. Forced to buy, unable to sell they say. Nobody, especially at Credit Suisse, seems to want to account for the possibility dealers may instead be unwilling to sell – which this isn’t the first time we’ve seen this behavior (see above).

And why wouldn’t you sell, if you could, given how much problem this is apparently causing in repo? It is not pure coincidence that dealer inventories rose sharply during past liquidity problems, including 2008 and 2011. Bond yields were falling, meaning prices rising sharply, during those times, too.

How do we know which is which? Very, very easy. Every single price and yield up and down the curve says there is and has been overwhelming demand in the financial public for UST’s. So much so, people and financial entities are willing to pay premiums on them, to gain less in yield for UST’s than they would through other financial alternatives (such as the Fed’s reverse repo; why are T-bills yielding less than the RRP if there isn’t excessive demand for T-bills?)

If you are in the camp of dealers stuck with UST’s, then special factors. If you instead look at actual price evidence and apply basic common sense, dealers purposefully hoarding UST’s, unwilling to part with them apparently at any price, then you appreciate the significance of building systemic pressures which is instead more and more exposed by what are normal calendar bottlenecks no one would ever otherwise notice. The problem is therefore so much bigger than the fiscal US government deficit. Systemic monetary problem.

And so, ultimately, if dealers aren’t willing to sell UST’s, and that’s what all the evidence says, why would they be hoarding them like this? Not because they fear a breakdown in fed funds, the Fed being backward about everything, but because they recognize the non-trivial risks of a breakdown in repo – which is merely confirmed by the increasingly abnormal behavior in fed funds as in other more relevant and important markets like swaps.

In one final sign of this clear progression early 2018 to now near Autumn 2019, the FOMC did vote today for another “technical adjustment” to IOER, the fourth. When the first one was announced and implemented all the way back in June 2018, it was something of a big deal. Today? Barely a footnote.

Stay In Touch