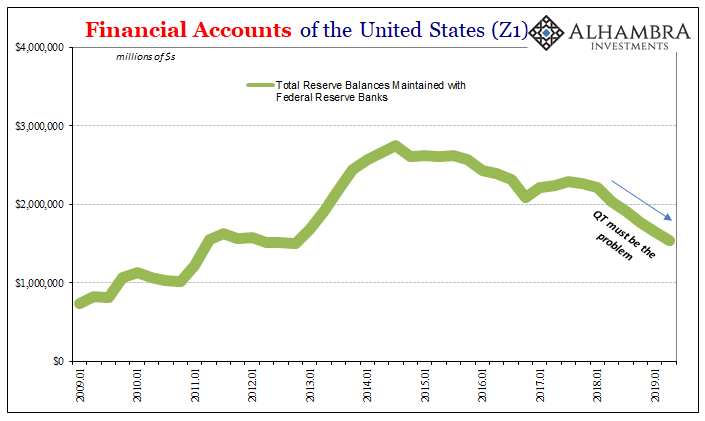

One of the most maddening aspects of the recent repo market, federal funds mashup is the lack of context behind it. The event is being characterized and described as if in isolation. Regulations are squeezing dealers at the same time there is a lack of bank reserves. Thanks to QT, there’s just not enough liquidity to go around.

Therefore, the Fed adds a repo facility of some type and, voila, back to our regularly scheduled programming. It all sounds very comforting.

The focus on bank reserves in reality is a total canard. A distraction. It’s difficult, though, to process and appreciate what I mean by that. Bank reserves, we are constantly reassured, are base money. So how can it be anything other?

I don’t agree at all with that proposition, but let’s treat them that way anyway just for illustrative purposes. Therefore, what’s been going on with IOER, fed funds, and repo appears to be the simple function of quantity. In this view of them, the Fed needs to find that magic number, the right level of “base money” to provide the system with the liquidity it requires – an amount which might change given circumstances.

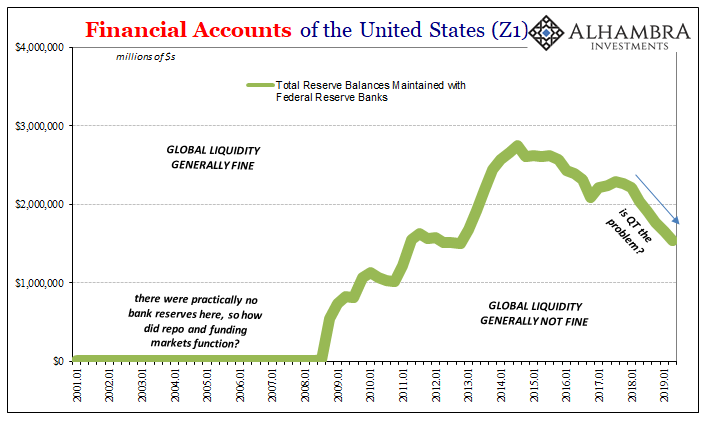

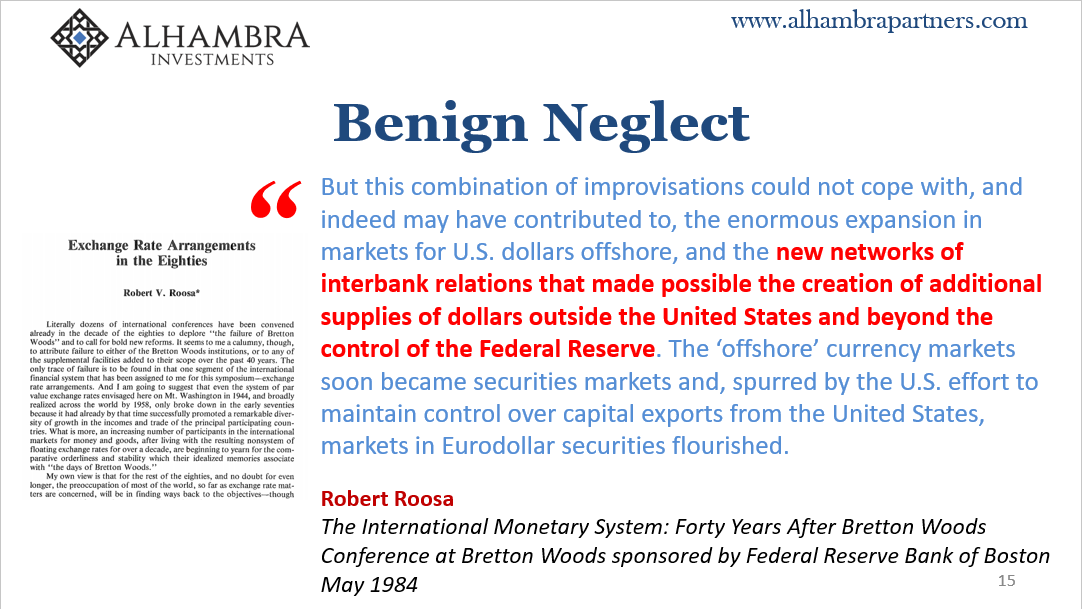

But that already proposes a big problem. The repo market didn’t just spring up out of nowhere around 2009. There was a quite robust repo market as part of a quite robust wholesale funding framework which dated back many decades.

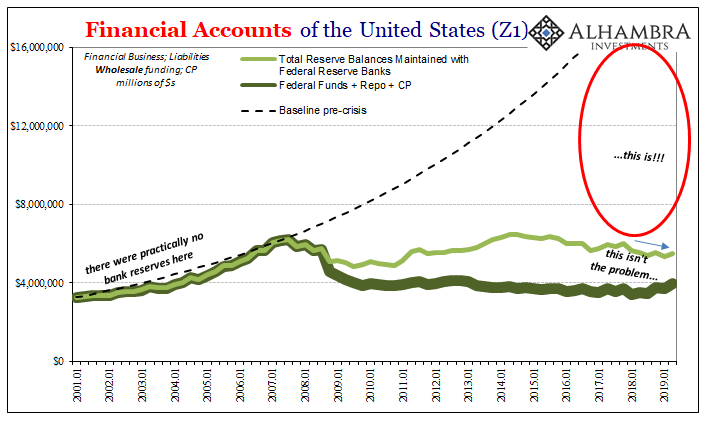

The key difference is that bank reserves were never a part of them. Before the onset of the second phase of the crisis in 2008, there were practically no bank reserves and yet “somehow” the funding markets operated anyway. Hardly anyone knew anything about them, that’s just how little they needed the Fed or its “base money.” Humming along quietly in the background, it all just worked out.

In short, the very idea of “liquidity” cannot just be limited to bank reserves. Again, even if we assume they form an aspect of “base money”, they can only be one aspect. Bank reserves are not, and cannot be, the complete picture of wholesale liquidity. There has to be a lot more going on in these money markets than what the Fed has been able to offer.

And that’s very curious because, as I pointed out in detail here, the entire global “bond market” generally behaved as if liquidity was fine before 2008 when there were practically no bank reserves. Following 2008, it’s been a very clearly defined series of global dollar shortages, including one which began coincident to QT.

Without any bank reserves, bond yields, eurodollar futures, inflation expectations, swaps spreads, etc., all looked and behaved like normal. Starting with the introduction of bank reserves, as well as their eventual removal, those same indications are all progressing further and further away from normal – independent of their level at whatever period in time.

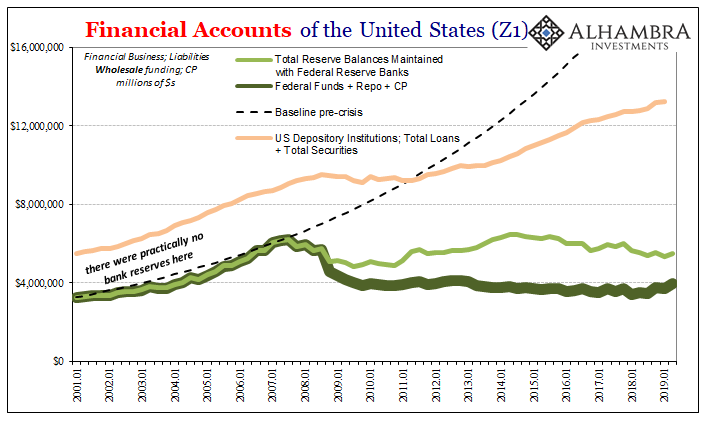

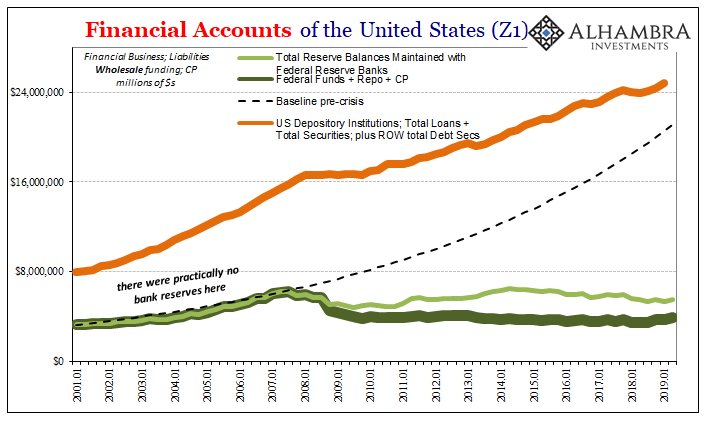

Liquidity and funding together must be a much bigger concept than bank reserves alone. And to show you what I mean I’ll put some numbers to it.

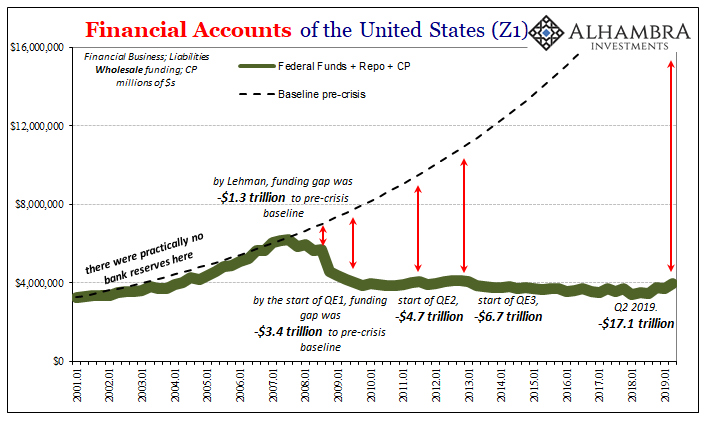

Keep in mind that what data we do have available is at best partial estimates and reconstructions, and therefore there are more pieces to the larger “liquidity” puzzle left undefined. Even with incomplete proxies you begin to see what I mean. Funding markets didn’t require any contributions from the Fed because private capacities supplied whatever was needed, as it was needed, and in the form it was needed.

This was all three of Robert Solomon’s three pillars of any global reserve currency: liquidity, adjustment, and confidence. Whether it was in fed funds, unsecured eurodollars (not pictured above), or even FX (also not pictured), the global eurodollar marketplace was a zoo of different forms of liquidity and funding (making it difficult to classify anything as “base money”).

In just these several categories, you can already see the crisis as well as appreciate the scale of it. By the time Lehman Brothers failed (coincidentally at a seasonal low point in liquidity just two weeks before the end of the third quarter of 2008), our minimal wholesale liquidity proxies were down well more than $1 trillion to the precrisis baseline. And it would quickly grow to become several trillion as the Global Financial Crisis sprung into full destructive capacity.

So, if we overlay the Federal Reserve’s “base money” contribution from the crisis and after, the products of various emergency “liquidity” programs and then four (yes, four) QE’s, it’s not nearly as impressive in the grand scheme of the wholesale funding paradigm.

In fact, it’s barely a drop in the bucket.

Therefore, when we look at the overall context and put the events of two weeks ago within it, what’s missing is not bank reserves and the Fed’s “base money” what’s missing is all the creative and adjustable forms of “liquidity” and funding that used to be regular pieces of the overall wholesale marketplace.

I keep asking where are the dealers, and this is the big picture behind what I mean. They aren’t constrained by the level of bank reserves, they are being constrained by forces far, far bigger than that.

And it isn’t regulations, either.

It is a behavioral change with profound consequences – big and small. Liquidity uncertainty is a major piece of the world’s problems, and it’s much larger and more widespread than what is pictured here by partial proxies and incomplete data focused solely on the domestic end of what is a global reserve system (eurodollar).

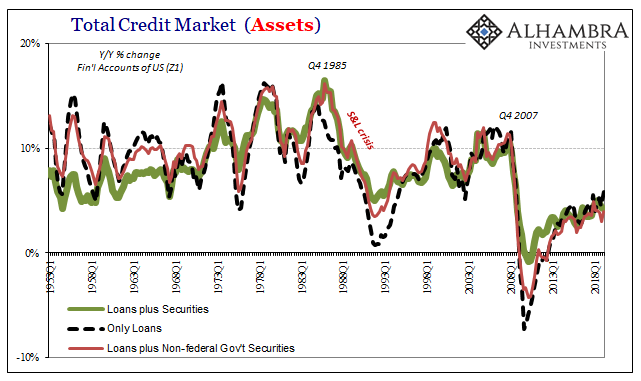

The credit markets, loans and securities, have been completely upended since 2008. It wasn’t Dodd-Frank which engineered that inflection and major change in performance. The coincidence to liquidity factors, even those just pictured here, are too much to ignore – especially when you consider how bank reserves are dubious as “base money” anyway.

The funding system used to be a real zoo, full of all sorts of exotic species of “liquidity” all provided by a private (and global) banking system which readily (and greedily) participated in it because it seemed to be one of only asymmetric positives – all return, no risk. Since Bear Stearns, it’s been all risk, no return. The animals in the zoo have more and more been left to die off over time.

So, while the mainstream focuses on the perceived health of those few animals which remain, including the least interesting specimen around, bank reserves, no one seems to (want to) notice just how unpopulated and vacant the whole zoo has become. It’s not the level of bank reserves. It’s the increasingly empty zoo.

Stay In Touch