It wasn’t just you, me, and common sense which were puzzled by the labor shortage of 2018. In his first few months on the job, Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell would reference the unemployment rate quite often in setting his view of the economy’s trajectory. As it fell lower and lower, it spiked his expectations for inflationary pressures.

The level to which it was falling, though, seemed consistent with a downright shortage of workers. This was backed up by anecdotes coming in throughout the central bank’s vast network of contacts. The Beige Book would soon fill with references to human resource struggles and the mainstream media never went more than a day without a story or two about how creative companies were forced to become in order to attract potential employees (while retaining those already inhouse).

But something was always missing. It wasn’t just “something”, either, it was really everything. Oddly enough, in his first broadcast interview as Chairman, Jay Powell admitted he didn’t have an answer for this. From July 12, 2018 (transcript):

Powell: So again, there’s no — I wouldn’t call it a mystery, but I would say that it’s a bit of a puzzle given how tight labor markets appear to be. And what we’re hearing from employers really is that they can’t find workers, and you’re wondering, well, why aren’t wages going up faster?

Ryssdal: Why aren’t they paying them, right?

Powell: It’s a good question. It’s a good question. We don’t really have the answer to that question.

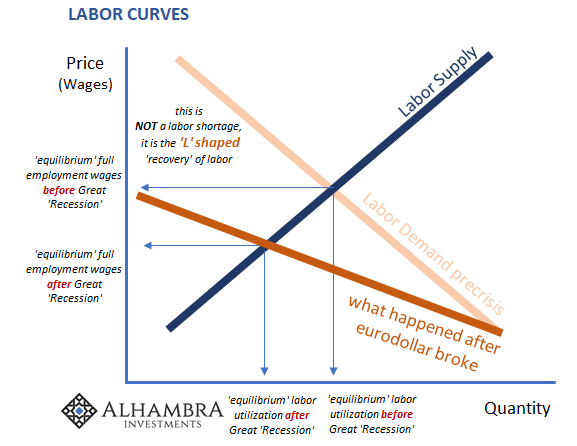

That’s not really true. They had an answer, it’s just not one they liked. Companies might’ve been having problems sourcing labor simply because they weren’t paying what the labor market demanded. Very simple, very basic small “e” economics; supply and demand. Pay the market clearing wage, and like magic all that nonsense disappears.

But that raised one very important and very uncomfortable question for Powell: how can the economy be booming, as he claimed, if companies wouldn’t or, more likely, weren’t able to pay the clearing wage rate(s)?

“Something” isn’t missing, it might be the whole thing which was missing.

And it wasn’t just labor costs where this economic constraint had been showing up. Somewhat counterintuitively, commodity costs behave in the same manner. We think that, because we are taught that, when commodity prices rise that’s a bad sign of companies being squeezed inside their cost structure. The bottom line will surely suffer.

Not true. When commodity prices rise it is because, like wages and the labor rate, companies can easily afford to pay those higher prices. They are more concerned about maintaining growth on the top line. Material producers are able to pass along price increases only at times when their customers are able to absorb them. When there is economic growth, there is expansion all throughout. Including prices.

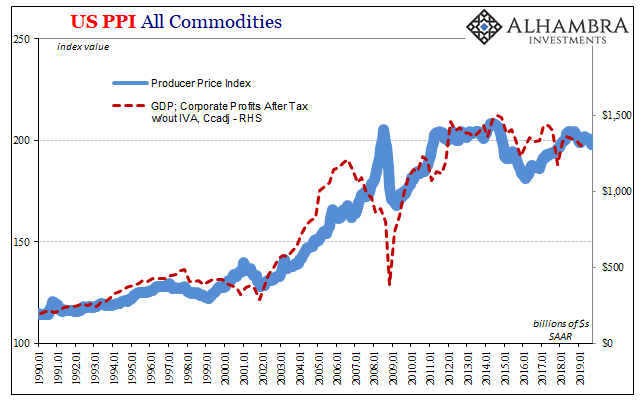

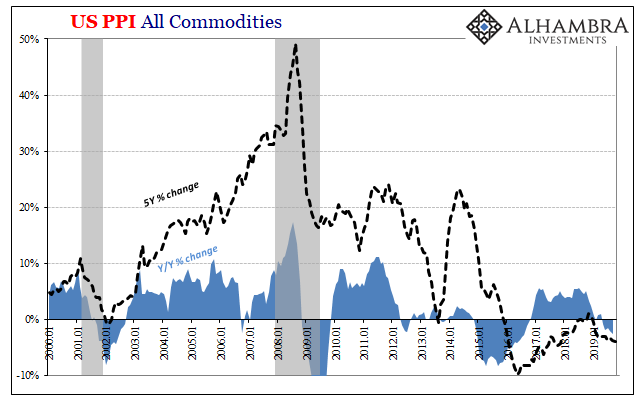

That’s why you can plot something like the PPI index alongside GDP’s corporate profits series and they come out in very close correlation:

When companies are raking in the profits they are paying more input costs for materials as well as labor. If they aren’t increasing their profits, they aren’t doing either of those things. And that describes the world since 2008, especially since 2011.

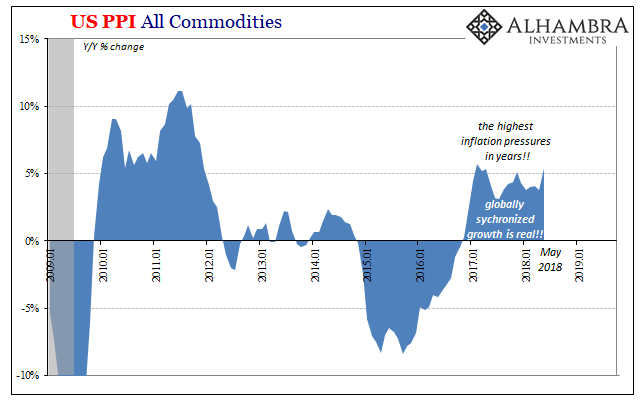

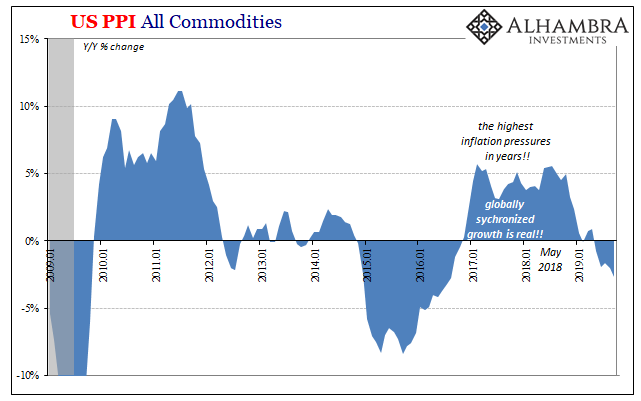

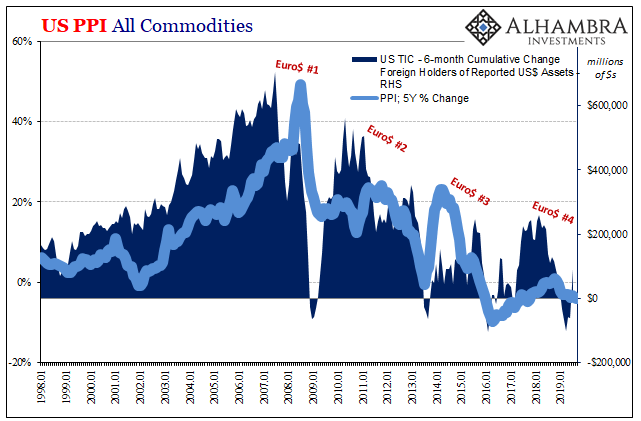

What that meant for more recent times was officials like Janet Yellen, Mario Draghi, and Powell making a huge mistake in interpreting 2017. Yes, globally synchronized growth. Looking at it from yearly changes, as we all do, something like price pressures captured by the PPI seemed impressive and therefore meaningful. Input prices were rising at a rate not seen since the early years of the “recovery”, feeding Powell’s inflationary narrative in parallel to the LABOR SHORTAGE!!!

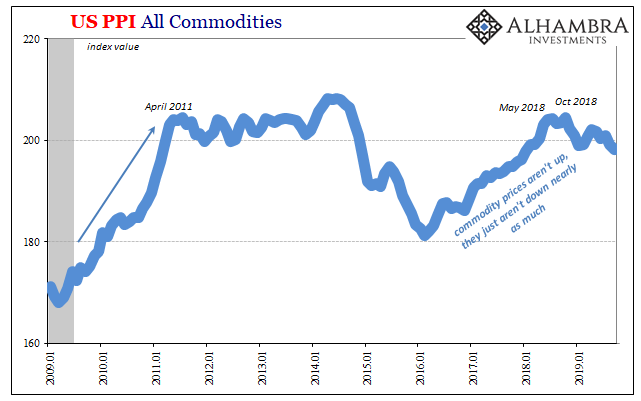

But if you don’t see and recognize the huge, sustained decline which came before it, you make the mistake of not holding to scale. You can see what I mean when you look at it as just the index value rather than the year-over-year changes:

You can’t help but notice instead that commodity prices, like corporate profits, have been flat or slightly lower for years. They weren’t really up in 2017 so much as rebounding from Euro$ #3 toward that level baseline which has existed ever since Euro$ #2 began to erupt more than eight years ago.

With that relative context, globally synchronized growth looks(ed) so much less impressive. If we use instead a 5-year rolling PPI comparison, it practically disappears.

Using this perspective, what we find is nothing but continued trouble; an economy that seems to have stepped down after 2009, recovered partially, and then stepped down again. That would seem to answer Mr. Powell’s wage puzzle. The PPI, like muted wage growth, suggests companies just were not able to pay higher prices – so they stopped paying higher prices.

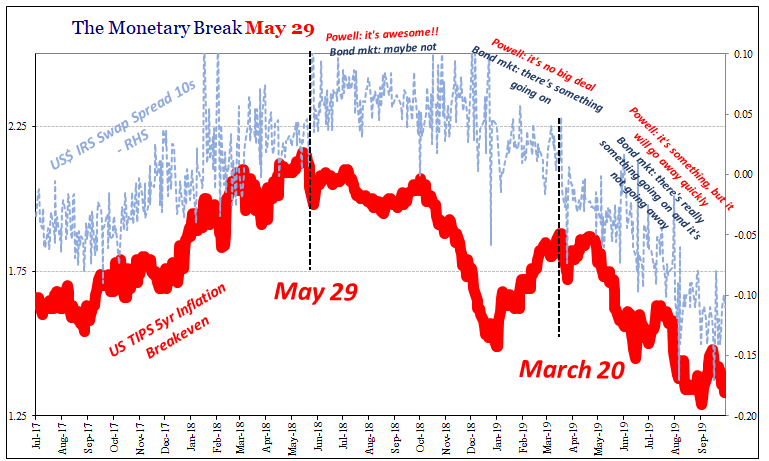

And that’s actually the baseline setting before ever getting to Euro$ #4 – which became more obvious around May 2018, more than a month before the Fed Chairman would give that particular interview. Not only was there no boom, or at best a questionable one, it was already unraveling while he was desperately trying to avoid the hard questions in favor of keeping up the narrative.

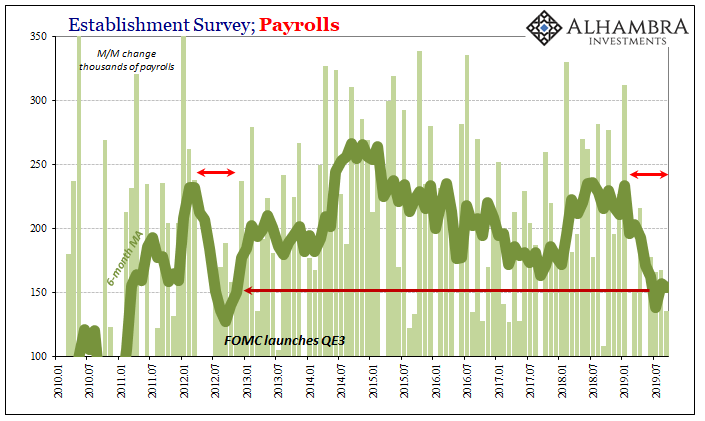

An epic labor market, the lowest unemployment rate in 50 years would otherwise seem to be signals of a rock-solid economy. That’s just what Economists and policymakers have been saying ever since around May 2018. They’ve adjusted their views along the way: first there was no issue, then it was “transitory” factors, and now it’s cross currents or some such. A mid-cycle adjustment.

What kind of cycle, though?

That view depends entirely upon never answering the original question: why weren’t companies paying the prevailing wage rate? If it was, and is, because they couldn’t, then we have our answer about the labor market – and the increasing economic risks in 2019.

In that way, commodity prices are an indication of actual economic conditions in business. In addition to labor market data that already shows a great deal of strain on employers, we now have the PPI falling again confirming that the collective ability of companies to pay up for more inputs has materially changed.

Not for the better, obviously. With producer and commodity prices falling, and the rate of job growth with it, there’s significantly more weakness in the US economy than Powell is otherwise admitting. Whether he actually knows it and is keeping his true concern to himself is a separate question. Two rate cuts already suggest as much.

His real problem, and the one facing global businesses not just their American counterparts, is the same problem that showed up in advance of 2008. The reason businesses can’t pay more for workers and won’t pay more for materials is that there is no economic growth by which the whole system would be advancing together.

There has been no real business cycle since August 2007.

Instead, for the fourth time, the whole global system is retreating together. Not all at once, not as a violent crash, but as a slow squeeze and strangulation that’s taken more than a year before it has become (largely) undeniable. The risks of something worse can only grow, which is further reflected in corporate conditions.

And the reason why there is no economic growth is simply that central bankers don’t know their job. They think their job is to make you believe they know what they are doing – whether they do or not. Companies, however, can’t pay for more workers and raw materials with puppet show tickets. So they don’t.

Stay In Touch