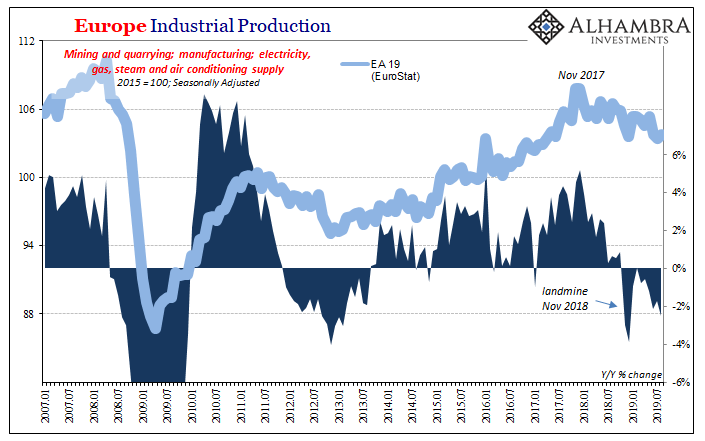

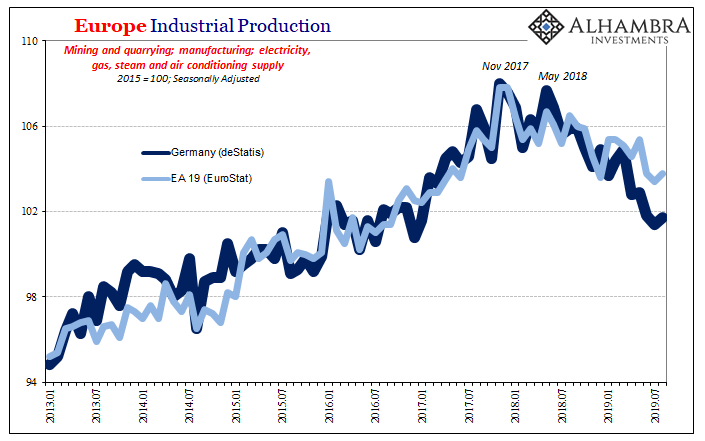

It’s not that they are different types, these are only differences in time and timing. As I wrote yesterday, the US economy is on the same spectrum following in behind Europe’s lengthy head start. American Industrial Production peaked a year later and only now has turned negative year-over-year, while European Industrial Production peaked way back at the end of 2017 and has been consistently negative since last November’s landmine.

What’s important to note about European industry and manufacturing isn’t really the depth of its decline, though that’s significant already, rather how there is still no end in sight. It can boggle the mind how a serious economic problem like this can continue for as long as it has and keep getting worse while it does.

According to Eurostat, IP for the nineteen countries of the Euro Area fell by 2.5% year-over-year in August 2019. That may not sound like all that much, but for a statistic like Industrial Production that level of decline is very much recession-like. During the 2012 European recession, the worst single month was -4.0% and there was only a total of five months that ended up being below -2.5%.

The problem isn’t just Germany but it is in large part due to Germany’s external stumble. The falling euro not trade wars has ended up being the biggest negative factor, which is the opposite of how it is supposed to go.

A weaker currency should (and does) make goods produced under those terms relatively cheaper for export. Demand would otherwise increase for them – if there weren’t other factors involved.

In Germany’s case, and therefore Europe’s, the focus shouldn’t be on the falling euro but the rising dollar on the other side. A global dollar shortage is a more potent anti-stimulus. That’s why going back to last May (29) when that shortage kicked into a higher gear the German (and European) economy was pushed toward an even lower level.

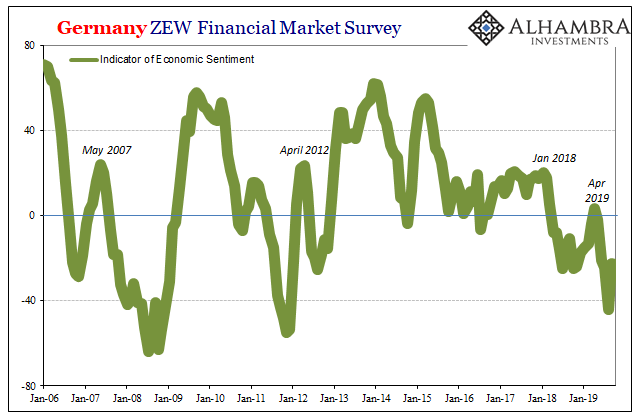

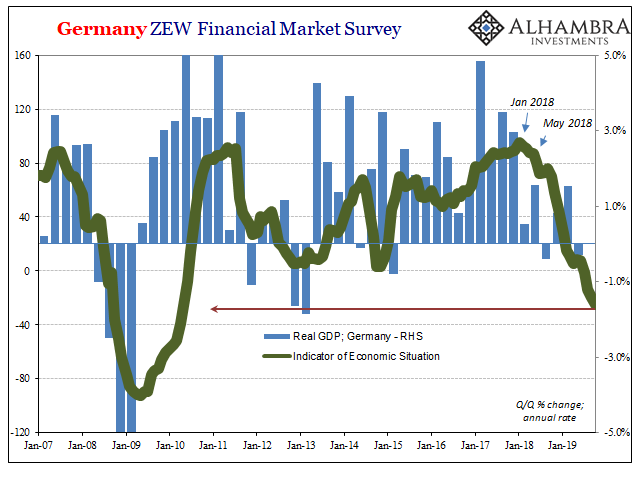

Despite what is now nearly two years facing these strong and increasing eurodollar headwinds, there’s no sign that they are abating – and plenty that suggest they are accelerating (not just US$ repo problems). In terms of fallout in at least Germany’s economy, forward-looking indicators like the ZEW’s surveys continue to point to even more downside to come.

Even the IMF has to admit this is a globally synchronized downturn in the broadest sense. The direction may be what’s currently synchronized, but there is still variation in timing as well as the degree and depth of the condition across the global economy. As the pull of synchronization grows stronger, though, does the US economy start to look less like Europe’s?

Stay In Touch